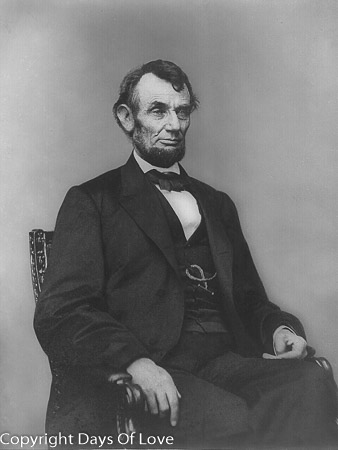

Abraham Lincoln[1] (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American statesman and lawyer who served as the 16th President of the United States from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865.

The revelation that Abraham Lincoln shared a double bed (and his most private

thoughts) for almost four years with general store proprietor Joshua Fry

Speed as he started out on his illustrious career in Springfield,

Illinois, has attracted a great deal of attention, leading on the one hand to

claims that this means he was “gay” and on the other to attempts to use this

piece of history to raise awareness of the different ways that male intimacy

could be expressed in the past.

Abraham Lincoln[1] (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American statesman and lawyer who served as the 16th President of the United States from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865.

The revelation that Abraham Lincoln shared a double bed (and his most private

thoughts) for almost four years with general store proprietor Joshua Fry

Speed as he started out on his illustrious career in Springfield,

Illinois, has attracted a great deal of attention, leading on the one hand to

claims that this means he was “gay” and on the other to attempts to use this

piece of history to raise awareness of the different ways that male intimacy

could be expressed in the past.

In The Prairie Years, the 1926 biography of the president, Carl Sandburg noted the “streak of lavender” and “spots soft as May violets” that ran through Lincoln and Joshua Fry Speed, who slept together nightly for four years in a bed above the Springfield store where Lincoln clerked. C.A. Tripp’s posthumously published The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln (2005) suggests that Sandburg’s publisher had purged the suggestive homoerotic 1926 references from later editions. In his study, Tripp introduced a handful of other men whom he suggests were intimate with Lincoln and were among the subjects subjects of what Sandburg called the “invisible companionships that surprised me,” mentioned in his research of “stacks and bundles of fact and legend”: William “Billy” Greene, with whom Lincoln shared a bed in New Salem so narrow that when one turned, the other had to turn also; Army Capt. (later Maj.) David V. Derickson, who frequently shared the president’s bed when Mary was absent; Col. Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, with whom Lincoln had a “knight and squire” relationship and who was killed in the Civil War; Abner Y. Ellis, who came to Springfield and took quite a “fancy” to Lincoln and ended up in his bed; and others.

Lincoln led the United States through its Civil War—its bloodiest war and perhaps its greatest moral, constitutional, and political crisis.[2] [3] In doing so, he preserved the Union, paved the way for the abolition of slavery, strengthened the federal government, and modernized the economy.Abraham Lincoln and Joshua Fry Speed first met on April 15, 1837, the day Lincoln rode into Springfield, IL, on a borrowed horse, carrying a pair of saddlebags, two or three law books, and some clothing. Lincoln had first been elected to the Illinois legislature three years earlier, and Speed had heard him speak publicly, but had not met him. Lincoln "came into my store... set his saddle bags on the counter," and asked about the price of bedding for "a single bedstead," Speed recalled many years later. Hearing the cost, Lincoln said, "Cheap as it is I have not the money to pay. But if you will credit me until Christmas... I will pay you then." If he failed as a lawyer, said Lincoln, "I will probably never be able to pay you at all." " The tone of his voice," Speed remembered, "was so melancholy that I felt for him." Looking up at the tall Lincoln, Speed "thought then, as I think now, that I never saw so gloomy and melancholy a face in my life." Spped then spontaneously proposed a no-cost arrangement. "I have a very large room, and a very large double-bed in it; which you are perfectly welcome to share with me if you choose." "Where is your room?" Lincoln responded. Speed pointed to the stairs, and "without saying a work Lincoln toook his saddle bags on his arms, went upstairs, set them down on the floor, came down again, and with a face beaming with pleasure and smiles, exclaimed, "Well, Speed, I'm moved."

As Speed himself described his and Lincoln's friendship at its height, "no two men were ever more intimate." Lincoln "disclosed his whole heart to me," Speed told William Herndon, Lincoln's onetime law partner and chronicler. Lincoln "loved this man more than anyone dead or living," said Herndon, not excepting Mary Todd. A recent biographer called Speed "the only intimate friend that Lincoln ever had," a judgment seconded by others.

In 1838 Speed hired the young William Herndon to clerk in his general store. Herndon later recalled that he, Speed, Lincoln, and Charles R. Hurst (another clerk), "slept in the room upstairs over the store."

Lincoln never spoke of "any particular woman with direspect," Abner Y. Ellis assured posterity, "though he had many opportunities for doing so." Lincoln told "the boys... stories which drew them after him," recalled Ellis, "but modesty and my veneration for his memory forbids me to relate." Lincoln's sex stories drew men to him, Ellis make clear.

Lincoln first met Mary Todd in the Springfield home of her sister, Elizabeth Edwards, who had married into one of the richest families in Illinois. Bu the fall of 1840 Todd and Lincoln were edging toward engagement, and sometime around Christmas 1840 they may have become engaged.

On March 30, 1840, Judge John Speed died. Joshua announced plans to sell his store and return to his parent's large plantation house, Farmington, near Louisville, Kentucky. Lincoln, though notoriously awkward and shy around women, was at the time engaged to Mary Todd, a vivacious, if temperamental, society girl, also from Kentucky. By December 1840, Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln may have understood their relationship as an engagement. But on New Year's Day 1841, Joshua Speed sold his interest in the Springfield general store in preparation for a return to his old Kentucky home. As the dates approached for both Speed's departure and Lincoln's own marriage, Lincoln broke the engagement on the planned day of the wedding (January 1, 1841). Speed departed as planned soon after, leaving Lincoln mired in depression and guilt.

In the summer of 1841, Lincoln visited Speed in Kentucky, where Lincoln's spirits greatly improved. But that summer Speed became engaged to Fanny Henning, setting off a new emotional crisis. Lincoln was actually in Kentucky when Speed courted Henning, Speed remembered, "and strange to say something of the same feeling which I regarded as so foolish in him... took possession of me... and kept me very unhappy from the time of my engagement until I was married." From early September 1841 to mid-February 1842, Speed shared his "immense suffering" with Lincoln, and Lincoln responded in several remarkably revealing letters. On January 1, 1842, Speed ended a Springfield visit with Lincoln and started back to Kentucky to marry his fiancée. Lincoln gave him an ostensibly encouraging letter to read on the trip. It was intended, he said, "to aid you, in case (which God forbid) you shall need any aid", Lincoln's first foreboding. Speed and Henning married on February 15, 1842. Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln married on November 4, 1842.

Elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1846, Lincoln promoted rapid modernization of the economy and opposed the Mexican–American War. After a single term, he returned to Illinois and resumed his successful law practice. Reentering politics in 1854, he became a leader in building the new Republican Party, which had a statewide majority in Illinois. As part of the 1858 campaign for US Senator from Illinois, Lincoln took part in a series of highly publicized debates with his opponent and rival, Democrat Stephen A. Douglas; Lincoln spoke out against the expansion of slavery, but lost the race to Douglas. In 1860, Lincoln secured the Republican Party presidential nomination as a moderate from a swing state, though most delegates originally favored other candidates. Though he gained very little support in the slaveholding states of the South, he swept the North and was elected president in 1860.An astute politician deeply involved with power issues in each state, Lincoln reached out to the War Democrats and managed his own re-election campaign in the 1864 presidential election. Anticipating the war's conclusion, Lincoln pushed a moderate view of Reconstruction, seeking to reunite the nation speedily through a policy of generous reconciliation in the face of lingering and bitter divisiveness.

On April 14, 1865, five days after the surrender of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, Lincoln was shot by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth and died the next day. Lincoln has been consistently ranked both by scholars[5] and the public[6] as among the greatest U.S. presidents.

My published books: