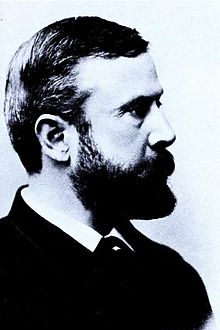

Alfred Corning Clark I (November 14, 1844 – April 8, 1896) was an

American

philanthropist.[1][2]

Alfred Corning Clark I (November 14, 1844 – April 8, 1896) was an

American

philanthropist.[1][2]Queer Places:

The Farmers' Museum, 5775 NY-80, Cooperstown, NY 13326, Stati Uniti

Dakota Apartments, 1 W 72nd St, New York, NY 10023, Stati Uniti

7 W 22nd St, New York, NY 10010

64 W 22nd St, New York, NY 10010

Hudson City Cemetery, 20 Columbia Turnpike, Hudson, NY 12534, Stati Uniti

Lakewood Cemetery, Cooperstown, New York 13326, Stati Uniti

Alfred Corning Clark I (November 14, 1844 – April 8, 1896) was an

American

philanthropist.[1][2]

Alfred Corning Clark I (November 14, 1844 – April 8, 1896) was an

American

philanthropist.[1][2]

Clark maintained three residences in Manhattan: a city house at 7 West 22nd Street for his family, a nearby flat at 64 West 22nd Street for guests, and a large apartment in The Dakota overlooking Central Park for entertaining.[4] Clark's father built The Dakota (1880–84), but died during its construction. Edward Cabot Clark skipped a generation and bequeathed the building to his 12-year-old grandson and namesake, Edward Severin Clark.[5]

Dakota Apartments, 1 W 72nd St, New York, NY 10023, Stati Uniti

7 W 22nd St

64 W 22nd St

Clark assembled a collection of French academic paintings. He purchased Pollice Verso (Thumbs Down) (1872) by Jean-Léon Gerome from the estate of Alexander Turney Stewart.[6] It is now in the collection of the Phoenix Art Museum. In 1888, he purchased Gerome's The Snake Charmer (1880), but his family sold it after his death. His son Sterling re-acquired the painting in 1942 for the museum he founded, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.[7]

According to Debby Applegate's review in the New York Times Book Review of Nicholas Fox Weber's group biography, The Clarks of Cooperstown (2007):

Weber suggests that Alfred [Corning Clark] led a dual life: a quiet family man in America and a gay aesthete in Europe, especially in France, which he declared "the Mecca of brotherly feeling." He was a generous patron to male artists; for 19 years his closest companion was a Norwegian tenor named Lorentz Severin Skougaard. When his father’s death forced him to return to Manhattan, Alfred installed Skougaard down the block from the town house where he lived with his wife and children. [Henry] James’s shadow lingers longest in this chapter; surely this was the sort of thing he meant by those uneasy intimations that beneath Europe’s splendor and refinement lurked something unspeakable. Weber’s bluntness, by contrast, highlights how much of that beauty was created by gay men seeking warm communities of free expression.[8]

Clark met Severin Skougaard (1837–1885) in Paris in 1866, where the singer was studying.[9] In 1869 – the same year that he married Elizabeth Scriven – Clark began making annual summer visits to Norway, eventually building a house on an island near Skougaard's family home.[9] He gave his son Edward, born 1870, the middle name Severin. When in New York City, Skougaard occupied Clark's flat at 64 West 22nd Street.[4] During an 1885 visit, Skougaard was strickened with typhoid and died.[9] Clark eulogized him in a privately published biographical sketch,[10] and created a $64,000 endowment in his memory for Manhattan's Norwegian Hospital, 4th Avenue & 46th Street.[11] Clark also commissioned Brotherly Love (1886–87) by American sculptor George Grey Barnard to adorn his friend's grave in Langesund, Norway.[12] The homoerotic sculpture depicts two nude male figures blindly reaching out to each other through the block of marble that separates them.[13]

Clark became Barnard's patron, commissioning works and providing financial support to him in Paris.[9] Clark paid Barnard $25,000 to carve a marble version of his Struggle of the Two Natures in Man (1888), which was completed in April 1894.[14] Barnard exhibited the piece at the 1894 Paris Salon, where the jury, headed by Auguste Rodin, pronounced it a work "of superlative merit."[14] Clark brought the larger-than-life-sized sculpture to New York City. Soon after his death, Clark's widow donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[14]

Clark died of pneumonia on April 8, 1896 in Manhattan, New York City.[1]

My published books:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Corning_Clark