Partner Maurice Brasseur

Queer Places:

8 Fitzroy St, London W1T 4BJ, UK

6 Baggot Street Lower, Dublin, D02 RX08, Ireland

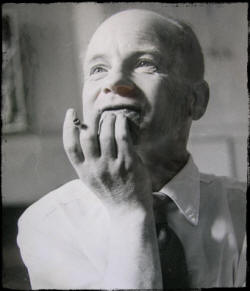

Basil Ivan Rákóczi

(May 31, 1908 – March 21, 1979) was an artist born in London. He was a prominent and leading member of the Irish art group, the White Stag, along with

Kenneth Hall.

Basil Ivan Rákóczi

(May 31, 1908 – March 21, 1979) was an artist born in London. He was a prominent and leading member of the Irish art group, the White Stag, along with

Kenneth Hall.

Rákóczi was born on 31 May 1908 in Chelsea, the son of Charlotte May Dobby, who was known as Dolly. His father, Ivan Rákóczi, whom his mother at some stage married in a gipsy rite, was Hungarian. The child was christened Benjamin Dobby Wilce, but he was known throughout his childhood and early manhood as Benjamin (Benny) Beaumont. This was the surname of his stepfather, Rev. Harold Ernst Beaumont, whom his mother had later married. In 1938, by deed poll, he adopted his father's surname and took the full name Basil Ivan Rákóczi, by which he was known thereafter.

Rákóczi's mother, Dolly, was the daughter of an Irish seaman who had settled in Kent and who is said to have married a Japanese woman of Irish extraction, but this is hearsay. Nevertheless till the end of his life Rákóczi proclaimed, with some pride, his Hungarian and Irish ancestry. Dolly spent a time on the stage before becoming an artist's model, at times (it is said) sitting for such distinguished painters as John Singer Sargent, Sir John Lavery, and Augustus John. Rákóczi knew his father only through his mother's reminiscences. 'She steadfastly maintained that [he] was an artist, musician and philosopher or yogi of Hungarian descent, who mostly lived in Paris', he wrote, although he had doubts as to the truth of the matter.

When Rákóczi was a baby his mother moved to the Hastings area, where in about 1911 or 1912 she met and married Harold Beaumont and together they reared the child as their son, as well as having their own child, Dudley, born in 1913. The marriage, however, was unhappy. Shortly after the outbreak of war, in August 1914, the Beaumonts moved to London and settled at Golders Green. In 1918 they moved to Brighton and, later, to Worthing in East Sussex, although the marriage continued to deteriorate as both partners turned increasingly to alcohol. Harold Beaumont died soon after the move to Worthing and at about the same time Dolly was admitted to a nursing home. In 1925, at the age of seventeen and with this unsettled childhood behind him, Rákóczi left home to make his own way in the world.

Basil Rákóczi was educated at the Jesuit College of St Francis Xavier in Brighton, before going to the Brighton School of Art and, later, to the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. In the late 1920s he worked for a time in London as a commercial artist and stage designer but gave this up to turn his attention to painting and psychology, two disciplines in which he was to retain a life-long interest. During, the 1930s he travelled widely in Europe, Egypt and India, where he is said to have met Gandhi, an experience which may have influenced his later views on pacifism. In 1930 Rákóczi married Natacha ('Tasche') Mather, but the marriage broke-up two years later and they were eventually divorced in 1938. They had one son, Anthony Pitcairn, who was born in 1931 and who became an actor. He died in Barbados in 1966.

In 1932 Rákóczi had taken a studio at number eight Fitzroy Street, London, and from that time onwards, till the end of his life, he concentrated his attention on his studies in art and psychology. In May 1935 with his friend Herbrand Ingouville-Williams, whom he had met in the early 1930s and who shared his interest in psychology, Rákóczi established the Society for Creative Psychology, the aim of which was to create a methodology in psychology attuned to what they termed 'the natural rhythm of life'. The activities of the Society, which met weekly in Fitzroy Street, centred mainly on discussions and sessions devoted to group therapy and psychoanalysis, but members - there were about thirty in all - often gave talks on a prearranged programme of subjects.

Rákóczi had himself undergone psychoanalysis from a friend, Karin Stephen, who was also a member of the Society for Creative Psychology. The Society for Creative Psychology thrived and its almost weekly meetings continued until the outbreak of war in 1939. At one of the Society's meetings, in July 1935, Rákóczi met Kenneth Hall, a struggling and impoverished artist. Hall was at the time subconsciously searching for the sort of companionship and lifestyle which Rákóczi offered and they formed a friendship which was to last until Hall's premature death. Rákóczi and Hall worked closely together, drawing inspiration from one another, and they shared a number of exhibitions at the Fitzroy Street studio. In the autumn of 1935 they established the White Stag Group for the advancement of subjectivity in art and psychological analysis, thus bringing together two of Rákóczi's passions as one activity.

In the late 1930s Rákóczi met the picture dealer Lucy Carrington Wertheim (1883-1971) who took an interest in his work. Lucy Wertheim ran a gallery in the Albany, London, specializing in the work of young artists. She clearly had a good 'eye' for amongst those whom she first brought to public attention were Barbara Hepworth (1903-75), Roger Hilton (1911-75), Robert Medley (b.1905), Victor Pasmore (b.1908), Christopher Wood, and the Irish painters Elizabeth Rivers (1903-64) and Norah McGuinness (1903-80), all of whom were members of her 'Twenties Group’ - artists aged between twenty and thirty. Rákóczi and Lucy Wertheim became friends and began a correspondence which continued until the latter's death in 1971. Lucy Wertheim was also impressed with Kenneth Hall's paintings and, in the late thirties, gave him a number of one-man exhibitions at her gallery as well as including him in several group exhibitions. In October 1938, during a visit to Paris, where Rákóczi and Hall were briefly staying, Wertheim introduced them to Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and to the well-known German collector and dealer Wilhelm Uhde, but nothing seems to have come from the meeting. On the outbreak of war in September 1939 the Wertheim Gallery closed with the premises requisitioned for use as an air-raid shelter. At that same time Rákóczi, Hall and Ingouville-Williams all moved to Ireland.

Why they chose to come to Ireland is unknown. In the first instance, as pacifists, they no doubt wished to avoid conscription, but Rákóczi also had a strong sense of heritage and perhaps too his mother's origins called him. Hall also had minor Irish connections, his mother having been born in Cork. At any rate the three friends travelled to the west of Ireland and settled near Leenane on Killary Harbour. They were happy there, if a little isolated. During the winter of 1939-40 Rákóczi made a few trips to Dublin where, amongst other things, he had to arrange schooling for his son, Tony, who was with him throughout his time in Ireland. He also surveyed the art scene there - 'Dublin ... is all agog for new art but I fear it is not very modern as yet', he told Lucy Wertheim - with a view to establishing a base. Eventually, in late February 1940 Rákóczi, Hall and Ingouville-Williams moved to Dublin, taking rooms in Lower Baggot Street, Upper Mount Street, and Fitzwilliam Square respectively. Ingouville-Williams registered for medical studies with the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland and practised both privately and at a local mental hospital.

Rákóczi and Hall were gregarious and they soon gathered around them in Dublin a small circle of friends who shared their interests. As in London they arranged lectures and discussion groups, which were open to all- comers, under the auspices of the Society for Creative Psychology and held exhibitions of paintings under the name of the White Stag Group. Judging by the names of those who were drawn into their company - Evie Hone, Mainie Jellett, Nano Reid, Michael Scott, Patrick Scott, Doreen Vanston, to name but a few - Rákóczi and his friends quickly established themselves in the Dublin art scene. The city clearly provided the sort of atmosphere in which they could thrive and, being the capital of a State neutral in the war, there was in the air a certain intrigue to which Rákóczi and many of those associated with the White Stag Group were not immune.

The six years he was to spend in Ireland were, despite his difficulties, a relatively prosperous time for Rákóczi. Besides his painting, he earned a meagre, but relatively constant, living working as an analyst. Kenneth Hall, who was desperately poor, worked solely at his painting. Writing to Lucy Wertheim in September 1940 Rákóczi opined that Norah McGuinness and Mainie Jellett were 'the most advanced artists here except for a man called Stephen Gilbert and his wife Jocelyn Chewett (1906-79) who is a sculptress’. He also thought that Hall's work shone out 'above the other artists' in Dublin. During their time in Ireland Rákóczi and his companions travelled quite widely, often visiting the West where they stayed with friends such as Dorothy Blackham (1896-1975) and other acquaintances. In June 1942, for example, Rákóczi was on Aran, staying at Kilmurvy with Elizabeth Rivers in her cottage, which had been 'used by Flaherty in his film "Man of Aran"', as he told Lucy Wertheim. 'It is an ideal place for an artist to paint in', he commented. In the same letter he complained of Dublin's boorishness towards modern art. The public here seem dreadful to us, for art or lectures. Crowds come, but they laugh and sneer most of the time'. 'Yet,’ he continued, 'there is a really appreciative and cultivated minority…that makes it all worthwhile’.

In comparison with the previous decade which, with a failed marriage, a lengthy legal battle (which he won) for the custody of his son, travels in Europe and elsewhere, had been a period of turmoil, the war years for Rákóczi brought relative stability. Yet throughout those years he had the exile's feeling of isolation. 'I am feeling deadly,’ he told Lucy Wertheim in September 1940, 'but the good things must triumph over the dark things of evil [i.e., war] and ignorance in the end I am sure'. In 1944 he wrote ‘I wept and sang when I heard Paris had been liberated'.

Kenneth Hall's health was a constant source of concern to Rákóczi. Hall had always been a highly nervous and somewhat sickly figure, suffering regular bouts of mastoiditis from the 1930s. He experienced a deep sense of exile during his years in Ireland and was plagued by financial difficulties. He bemoaned mainly though the fact that he lacked money to buy painting materials to satisfy his tremendous desire to paint. Much of Hall's ill-health seems to have been psychological, exacerbated by his isolation from his family. His father had cut him off completely because of his pacifism and this weighed heavily on him. 'Kenneth...is really very sick,' Rákóczi wrote as late as 1944, 'not at all helpful has been his father's attitude to him conveyed in letters from his brother...telling him that he must never come to the house again'. Yet despite all this Kenneth Hall was a most sensitive painter and produced some splendid work while in Ireland.

The high point of the activities of Rákóczi, Hall and the White Stag Group during their years in Ireland was the Exhibition of Subjective Art, which was held at 6 Lower Baggot Street in January 1944. The exhibition drew together those who were closest in sympathy with the Group's ideals and, following on the heels of the Irish Exhibition of Living Art, which had been staged for the first time just four months earlier, it did much to encourage all who were interested in creating a genuine Irish avant-garde. The exhibition was to have been opened by the influential English critic Herbert Read, but war-time travel restrictions prevented his attendance. However his endorsement of the pictures was later published in the Clive Bell and Cyril Connolly's influential journal, Horizon, also published an article on them. With these developments, not to mention the publication a year later of the book, Three Painters, which featured the work of Rákóczi, Hall and Patrick Scott, the work of the White Stag painters was brought to an ever wider audience.

Three Painters provided the definitive statement on Rákóczi's philosophy of Subjective Art, which was in effect a personal alignment with the broader theories of Surrealism, which had dominated the development of European art (but which had by passed Ireland) during the late 1920s and 1930s. The theoretical base of Subjective Art was well set-out by Ingouville-Williams in his introduction to the book: In Subjective Art...order and emotion are synthesized...but the theme, instead of being drawn from objects in the external world, is elaborated by the workings of the imagination turned inwards upon the memories, dreams and phantasies of the Unconscious. Objects which appear in Subjective paintings, such as a bird, a fish, a figure, or a garden, are not represented in a realistic manner, but as dream-images, as conceptual memories, as the eidetic phantasies of the child-mind.

The book had a mixed press in Dublin, but Maurice Collis, writing in the Observer, admired it and thought Rákóczi and company constituted 'a cosmopolitan corner in Dublin life', while a reviewer for the Listener found it both 'useful and convincing'.

Sadly, the main architect of Three Painters, Dr. Ingouville-Williams, had died in March 1945, just a few months before its publication. By then the war was drawing to a close and Rákóczi and Hall were thinking of returning to England and, ultimately, to France. Thus their activities in Ireland began to wind down. Yet, in that year the Group managed to hold six exhibitions.

Eventually, however, in September 1945 Hall returned to London, where he hoped to get new treatment for his ills, and later that autumn Rákóczi also moved to London before going to Paris. But Hall's depressions continued to plague him and, despite having some pictures in the Redfern Gallery's summer exhibition in 1946 - this should have been an enormous stimulus to him -he took his own life in July that year. This, coming so soon after Ingouville-Williams' death, left Rákóczi devastated. 'My heart is quite broken with Kenneth's death. I feel so terribly lonely and lost', he told Lucy Wertheim. It was the end of an era for him, for henceforth his life was occupied in the main with new friends, most of whom he met in post-war France where he had decided to settle and indeed he remained there for the rest of his life.

Once settled in Paris Rákóczi soon got down to painting and he re-established the Society for Creative Psychology, Paris Branch, through which he practised as a psycho-analyst and thus in part earned his living. By means of the Society he also kept in touch with Dublin, for his many friends there continued to hold regular meetings (Isabel Douglas acting as secretary) and they did so throughout the late 1940s, the 1950s and even into the early 1960s. Rákóczi was a frequent guest speaker at these meetings. He also continued to send works to the annual exhibitions of the Royal Hibernian Academy, the Watercolour Society of Ireland and to the Irish Exhibition of Living Art and, as is noted in the list of his exhibitions below, he held a number of one-man shows in Dublin between 1948 and 1954.

In the early post-war years he also exhibited regularly in Paris, Amsterdam, London, Brussels, New York and elsewhere. Besides his art and psychoanalysis, he also studied and wrote a good deal on a diverse range of subjects, including pacifism (he became a Quaker in Dublin), Zen Buddhism, the Kabbala, Gipsy lore and the Tarot.

In 1947 Rakoczi studied briefly with the influential sculptor Ossip Zadkine (1890-1967), working in stone and wood as well as painting. Also in 1947 he met the Belgian artist Maurice Brasseur (born c.l926), also known as Alexandre Sarres. They struck up a close friendship and eventually shared a studio at Montrouge, Paris, for many years. From the early 1950s together they collaborated on a number of publications, all of which were issued under the imprint of the 'Editions du Cerf Blanc' (White Stag Press), and which brought a new breadth to Rakoczi's art. Of these the most important perhaps are In the Beginning (1961), Apocalypse (1970) and Jacqueline Robinson's Et ce chant dans mon coeur... sept poemes (1971). They show Rákóczi to have had a genuine talent for graphic work and his illustration, 'God creating man in his own image', from In the Beginning, for example, is a tour de force by any standard.

In the years after the war Rákóczi travelled widely in France and the Low Countries but in 1961 he took a cottage in Fornalutx, Mallorca, which was to provide a regular summer retreat for him. The death in Barbados in 1966 of his only son, Anthony, to whom he was greatly attached, was a devastating blow and caused him to stop work completely for several months.

The last period of Rákóczi's active life, from the mid-sixties till the mid-seventies, was a happy and a productive time. Life continued as usual in Paris and he had a wealth of friends in many countries with whom he maintained a regular correspondence. Also, around 1971-2 a trip to Brittany brought a renewed vigour to his painting and resulted both in a substantial body of work, of which he could be well satisfied, and in a drawing together of a number of themes -love, the 'human condition', for example -which permeate his complete oeuvre. Also, in Brittany he rediscovered his Celtic roots in an atmosphere similar to that which he had earlier known in the west of Ireland. From 1976, alas, Rákóczi began to suffer serious ill health from which he would never quite recover and which forced him to stop painting altogether. He was frequently in hospital in Paris and, later, in London, where, on the 21st March 1979, he died.

My published books: