Queer Places:

Eton College, Windsor SL4 6DW, Regno Unito

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

4 Chesterfield St, Mayfair, London W1J 5JF, Regno Unito

Cimetière Prostestant, Rue du Magasin À Poudre, 14000 Caen, Francia

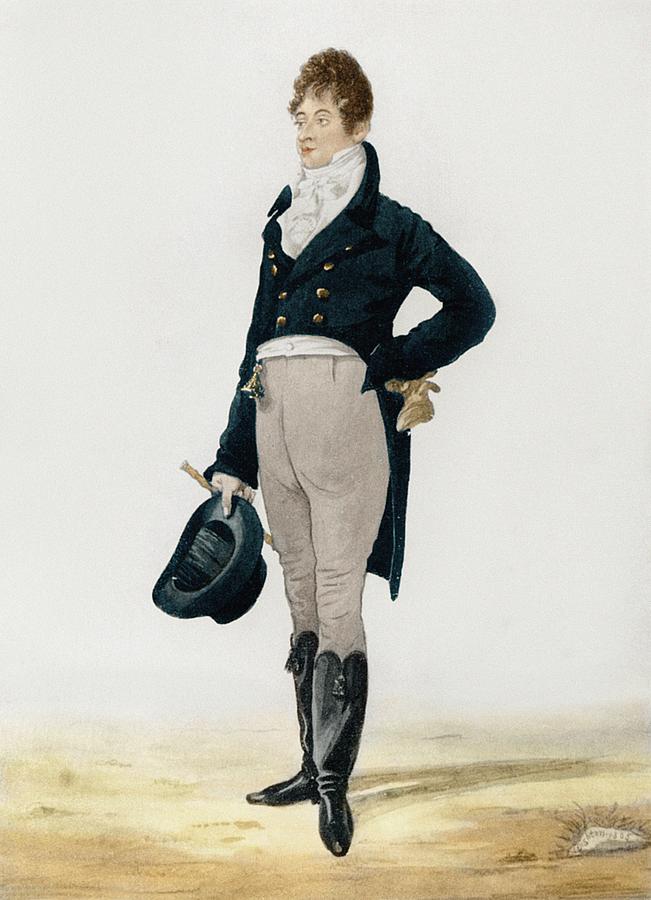

George Bryan "Beau" Brummell (7 June 1778 – 30 March 1840) was an iconic

figure in Regency England and for many years the arbiter of men's fashion. At

one time he was a close friend of the Prince Regent, the future King George

IV, but after the two quarrelled, and Brummell got into debt, he had to take

refuge in France. Eventually he died shabby and insane in Caen.

George Bryan "Beau" Brummell (7 June 1778 – 30 March 1840) was an iconic

figure in Regency England and for many years the arbiter of men's fashion. At

one time he was a close friend of the Prince Regent, the future King George

IV, but after the two quarrelled, and Brummell got into debt, he had to take

refuge in France. Eventually he died shabby and insane in Caen.

Brummell was remembered afterwards as the preeminent example of the dandy and a whole literature was founded upon his manner and witty sayings which has persisted to this day. His name is still associated with style and good looks, and it has been given to a variety of modern products to suggest their high quality.

Brummell was born in London, the younger son of William Brummell, a politician, of Donnington Grove in Berkshire. The family was middle class, but the elder Brummell was ambitious for his son to become a gentleman, and young George was raised with that understanding. Brummell was educated at Eton and made his precocious mark on fashion when he not only modernised the white stock, or cravat, that was the mark of the Eton boy, but added a gold buckle to it.[1]

He progressed to Oxford University, where, by his own example, he made cotton stockings and dingy cravats a thing of the past. While an undergraduate at Oriel College in 1793, he competed for the Chancellor's Prize for Latin Verse, coming second to Edward Copleston, who was later to become provost of his college.[2] He left the university after only a year at the age of sixteen.

In June 1794 Brummell joined the Tenth Royal Hussars as a cornet, the lowest rank of commissioned officer,[3] and soon after had his nose broken by a kick from a horse.[4] His father died in 1795, by which time Brummell had been promoted to lieutenant.[5] His father had left an inheritance of £65,000, of which Brummell was entitled to a third. Ordinarily a considerable sum, it was inadequate for the expenses of an aspiring officer in the personal regiment of the Prince of Wales. The officers, many of whom were heirs to noble titles and lands, "wore their estates upon their backs – some of them before they had inherited the paternal acres."[6] Officers in any military regiment were required to provide their own mounts and uniforms and to pay mess bills, but the 10th in particular had elaborate, nearly endless variations of uniform; also, their mess expenses were unusually high as the regiment did not stint itself on banquets or entertainment.

For such a junior officer, Brummell took the regiment by storm, fascinating the prince,

"the first gentleman of England", by the force of his personality. He was allowed to miss parade, shirk his duties and, in essence, do just as he pleased. Within three years, by 1796, he was made a captain, to the envy and disgust of older officers who felt that "our general’s friend was now the general."[6]

When his regiment was sent from London to Manchester, he immediately resigned his commission, citing the city's poor reputation, undistinguished ambience and want of culture and civility.[7]

Although he was now a civilian, Brummell's friendship with, and influence over, the Prince continued. It was now he became the arbiter of fashion and established the mode of dress for men that rejected overly ornate fashions for one of understated but perfectly fitted and tailored bespoke garments. This look was based on dark coats, full-length trousers rather than knee breeches and stockings, and above all, immaculate shirt linen and an elaborately knotted cravat.[8]

Brummell took a house on Chesterfield Street in Mayfair[9] and for a time managed to avoid the nightly gaming and other extravagances fashionable in such elevated circles. Where he refused to economise was on his dress: when asked how much it would cost to keep a single man in clothes, he was said to have replied: "Why, with tolerable economy, I think it might be done with £800." [10] That amount is approximately £52,000 ($67,000) in 2016 currency;[11] the average wage for a craftsman at that time was £52 a year. He also claimed that he took five hours a day to dress and recommended that boots be polished with champagne.[12] This preoccupation with dress, coupled with a nonchalant display of wit, was referred to as dandyism.

Brummell put into practice the principles of harmony of shape and contrast of colours with such a pleasing result that men of superior rank sought his opinion on their own dress.

The Duke of Bedford once did this touching a coat. Brummell examined his Grace with the cool impertinence which was his Grace’s due. He turned him about, scanned him with scrutinizing, contemptuous eye, and then taking the lapel between his dainty finger and thumb, he exclaimed in a tone of pitying wonder, “Bedford, do you call this thing a coat?”[13]

His personal habits, such as a fastidious attention to cleaning his teeth, shaving, and daily bathing exerted an influence on the ton - the upper echelons of polite society - who began to do likewise. Enthralled, the Prince would spend hours in Brummell's dressing room, witnessing the progress of his friend's lengthy morning toilette.

While at Eton Brummell played for the school’s first eleven,[14] although he is said to have once terrified a master there by asserting that he thought cricket "foolish".[15] He did, however, play a single first-class match for Hampshire at Lord's Old Ground in 1807 against an early England side. Brummell made scores of 23 and 3 on that occasion, leaving him with a career batting average of 13.00.[16]

Unfortunately, Brummell's wealthy friends had a less than satisfactory influence on him; he began spending and gambling as though his fortune were as ample as theirs. Such liberal outlay began to deplete his capital rapidly, and he found it increasingly difficult to maintain his lifestyle, although his prominent position in society still allowed him to float a line of credit. This changed in July 1813, at a masquerade ball jointly hosted at Watier's private club by Brummell, Lord Alvanley, Henry Mildmay and Henry Pierrepoint. The four were considered the prime movers of Watier's, dubbed "the Dandy Club" by Byron. The Prince Regent greeted Alvanley and Pierrepoint at the event, and then "cut" Brummell and Mildmay by staring at their faces without speaking.[17] This provoked Brummell's remark, "Alvanley, who's your fat friend?".

The incident marked the final breach in a rift between Brummell and the Regent that had opened in 1811, when the Prince became Regent and began abandoning all his old Whig friends.[18] Ordinarily, the loss of royal favour to a favourite meant social doom, but Brummell ran as much on the approval and friendship of other leaders of fashionable circles. He became the anomaly of a favourite flourishing without a patron, still influencing fashion and courted by a large segment of society.[19]

In 1816 Brummell, owing thousands of pounds, fled to France to escape debtor's prison. Usually Brummell's gambling obligations, as "debts of honour", were always paid immediately. The one exception to this was the final wager, dated March 1815 in White's betting book, which was marked "not paid, 20th January, 1816".[20]

He lived the remainder of his life in French exile, spending ten years in Calais without an official passport before acquiring an appointment to the consulate at Caen through the influence of Lord Alvanley and the Marquess of Worcester. This provided him with a small annuity but lasted only two years, when the Foreign Office took Brummell's recommendation to abolish the consulate. He had made it in the hope of being appointed to a more remunerative position elsewhere, but no new position was forthcoming.

Rapidly running out of money and grown increasingly slovenly in his dress, he was forced into debtors' prison by his long-unpaid Calais creditors; only through the charitable intervention of his friends in England was he able to secure release. In 1840 Brummell died penniless and insane from syphilis at Le Bon Sauveur Asylum on the outskirts of Caen; he was 61. He is buried at Cimetière Prostestant, Caen, France[21]

My published books: