Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Moonshine, Twilight Park, Haines Falls, NY 12436

Forest Hill Cemetery, 325 Forest Hill Rd, Fredericton, NB E3B 4K4

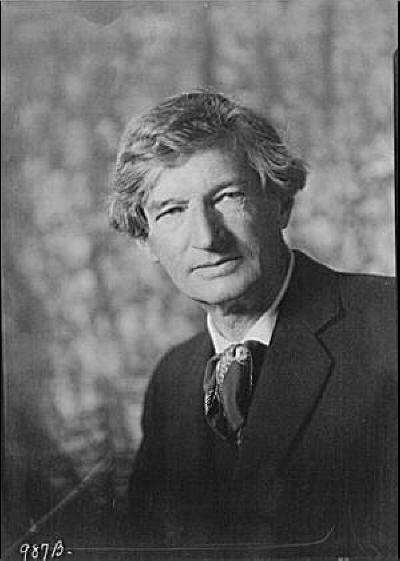

William

Bliss Carman FRSC (April 15, 1861 – June 8, 1929) was a Canadian poet who

lived most of his life in the United States, where he achieved international

fame. He was acclaimed as Canada's poet laureate[1]

during his later years.[2][3]

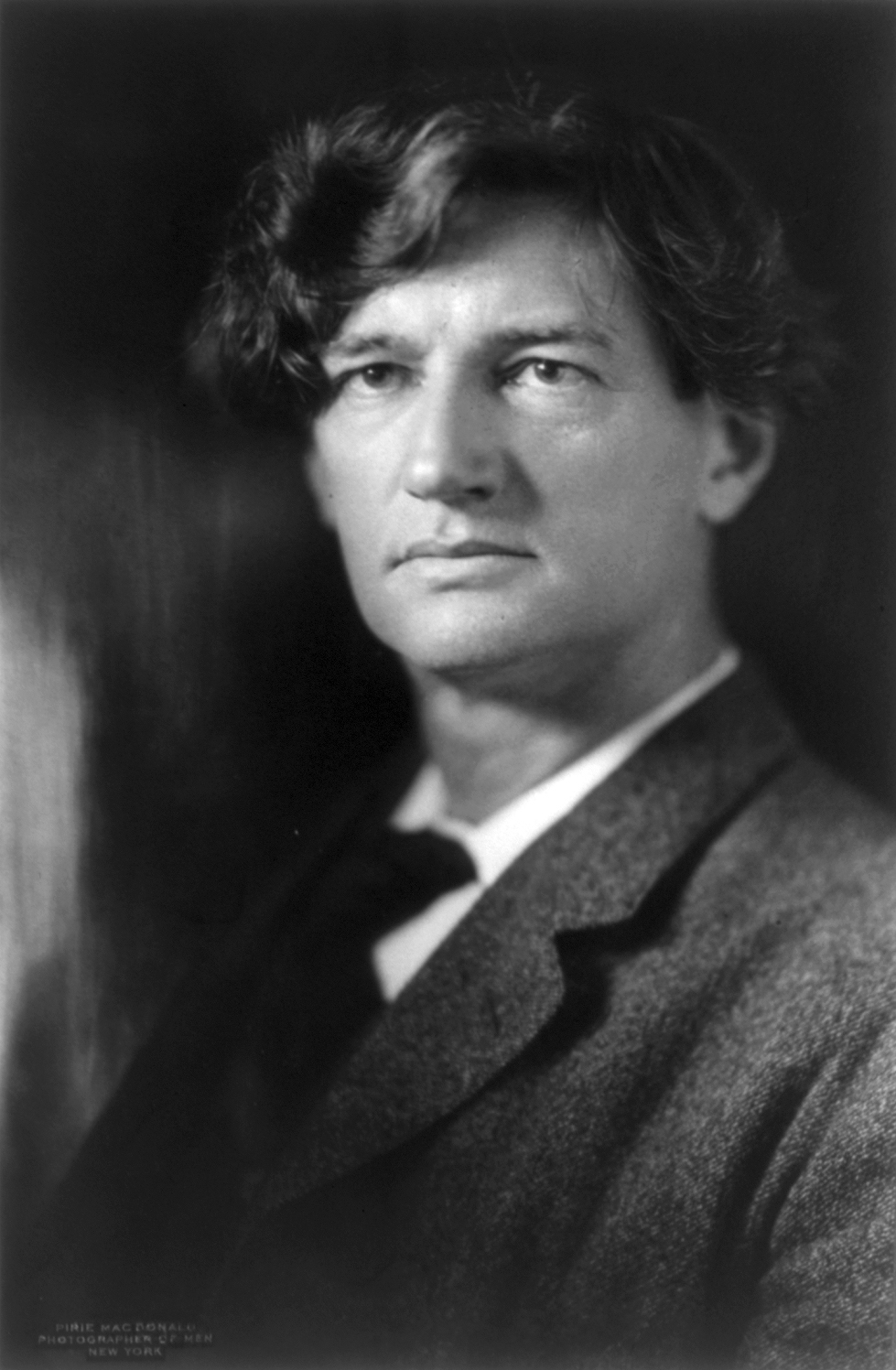

William

Bliss Carman FRSC (April 15, 1861 – June 8, 1929) was a Canadian poet who

lived most of his life in the United States, where he achieved international

fame. He was acclaimed as Canada's poet laureate[1]

during his later years.[2][3]

In Canada, Carman is classed as one of the Confederation Poets, a group

which also included Charles G.D. Roberts (his cousin), Archibald Lampman, and

Duncan Campbell Scott.[4]

"Of the group, Carman had the surest lyric touch and achieved the widest

international recognition. But unlike others, he never attempted to secure his

income by novel writing, popular journalism, or non-literary employment. He

remained a poet, supplementing his art with critical commentaries on literary

ideas, philosophy, and aesthetics."[5]

He was born William Bliss Carman in Fredericton, New Brunswick. "Bliss" was

his mother's maiden name. He was the great grandson[6]

of United Empire Loyalists who fled to Nova Scotia after the American

Revolution, settling in New Brunswick (then part of Nova Scotia).[7]

His literary roots run deep with an ancestry that includes a mother who was a

descendant of Daniel Bliss of Concord, Massachusetts, the great-grandfather of

Ralph Waldo Emerson. His sister, Jean, married the botanist and historian

William Francis Ganong. And on his mother's side he was a first cousin to

Charles (later Sir Charles) G. D. Roberts.[3]

He first joined the dance at Harvard as a graduate student in 1886 at age

twenty-five, and was—of course—linked to

George Santayana. Tall and

handsome, blond, and given to heavy tweeds, he was also apparently highly

flamboyant. “Carman wore his hair long and favored full flowing cravats,”

reports Roger Austen, and also affected “sandals and jewelry”—herald of

Edward Gorey. He, too, was as

convincingly summer as winter, vagabond in the country, fop in town.

The Visionists were very much involved in perpetuating, not bad magic, but

good art, particularly collaborative art, art by various members. A fine

example is the publication by the Visionists of Harvard poet (and Visionist

founder) Bliss Carman’s Ballad of St. Kavin in 1894, enshrined in an exquisite

design by architect Bertram Goodhue, not

a Harvard man, but whose cover showed not only the Visionists at supper but

the tower of Harvard’s Memorial Hall. Above all, there was Carman and

Richard Hovey’s poetry, published

together under the title Songs from Vagabondia. Carman’s biographer has

written that Carman’s particular friend was Hovey, and they reacted violently

upon each other, to the advantage of both.

by Arnold Genthe

In 1896 Carman met Mary Perry

King, who became the greatest and longest-lasting female influence in his

life. Mrs. King became his patron: "She put pence in his purse, and food in

his mouth, when he struck bottom and, what is more, she often put a song on

his lips when he despaired, and helped him sell it." According to Carman's

roommate, Mitchell Kennerley, "On rare occasions they had intimate relations

at 10 E. 16 which they always advised me of by leaving a bunch of violets —

Mary Perry's favorite flower — on the pillow of my bed."[14]

If he knew of the latter, Dr. King did not object: "He even supported her

involvement in the career of Bliss Carman to the extent that the situation

developed into something close to a ménage à trois" with the Kings.[3]

Through Mrs. King's influence Carman became an advocate of 'unitrinianism,'

a philosophy which "drew on the theories of François-Alexandre-Nicolas-Chéri

Delsarte to develop a strategy of mind-body-spirit harmonization aimed at

undoing the physical, psychological, and spiritual damage caused by urban

modernity."[7]

This shared belief created a bond between Mrs. King and Carman but estranged

him somewhat from his former friends.

In 1899 Lamson, Wolffe was taken over by the Boston firm of Small, Maynard

& Co., who had also acquired the rights to Low Tide... "The rights to

all Carman's books were now held by one publisher and, in lieu of earnings,

Carman took a financial stake in the company. When Small, Maynard failed in

1903, Carman lost all his assets."[5]

Down but not out, Carman signed with another Boston company, L.C. Page, and

began to churn out new work. Page published seven books of new Carman poetry

between 1902 and 1905. As well, the firm released three books based on

Carman's Transcript columns, and a prose work on unitrinianism, The

Making of Personality, that he'd written with Mrs. King.[12]

"Page also helped Carman rescue his 'dream project,' a deluxe edition of his

collected poetry to 1903.... Page acquired distribution rights with the

stipulation that the book be sold privately, by subscription. The project

failed; Carman was deeply disappointed and became disenchanted with Page,

whose grip on Carman's copyrights would prevent the publication of another

collected edition during Carman's lifetime."[5]

Carman also picked up some needed cash in 1904 as editor-in-chief of the

10-volume project, The World's Best Poetry.[7]

After 1908 Carman lived near the Kings' New Canaan, Connecticut, estate,

"Sunshine", or in the summer in a cabin near their summer home in the

Catskills, "Moonshine."[3]

Between 1908 and 1920, literary taste began to shift, and his fortunes and

health declined.[5]

"Although not a political activist, Carman during the First World War was a

member of the Vigilantes, who supported American entry into the conflict on

the Allied side."[15]

By 1920, Carman was impoverished and recovering from a near-fatal attack of

tuberculosis.[15]

That year he revisited Canada and "began the first of a series of successful

and relatively lucrative reading tours, discovering 'there is nothing worth

talking of in book sales compared with reading.'"[5]

"'Breathless attention, crowded halls, and a strange, profound enthusiasm such

as I never guessed could be,' he reported to a friend. 'And good thrifty money

too. Think of it! An entirely new life for me, and I am the most surprised

person in Canada.'" Carman was feted at "a dinner held by the newly formed

Canadian Authors' Association at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Montreal on 28

October 1921 where he was crowned Canada's Poet Laureate with a wreath of

maple leaves."[3]

The tours of Canada continued, and by 1925 Carman had finally acquired a

Canadian publisher. "McClelland & Stewart (Toronto) issued a collection of

selected earlier verses and became his main publisher. They benefited from

Carman's popularity and his revered position in Canadian literature, but no

one could convince L.C. Page to relinquish its copyrights. An edition of

collected poetry was published only after Carman's death, due greatly to the

persistence of his literary executor, Lorne Pierce."[5]

During the 1920s, Carman was a member of the Halifax literary and social

set, The Song Fishermen. In 1927 he edited The Oxford Book of American

Verse.[16]

Carman died of a brain hemorrhage at the age of 68 in New Canaan, and was

cremated in New Canaan. "It took two months, and the influence of New

Brunswick's Premier J.B.M. Baxter and Canadian Prime Minister W.L.M. King, for

Carman's ashes to be returned to Fredericton."[10]

"His ashes were buried in Forest Hill Cemetery, Fredericton, and a national

memorial service was held at the Anglican cathedral there." Twenty-five years

later, on May 13, 1954, a scarlet maple tree was planted at his gravesite, to

grant his request in his 1892 poem "The Grave-Tree":[7]

-

-

- Let me have a scarlet maple

- For the grave-tree at my head,

- With the quiet sun behind it,

- In the years when I am dead.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bliss_Carman

- Improper Bostonians Lesbian and Gay History from the Puritans to

Playland By History Project Staff · 1998

- Shand-Tucci, Douglass. The Crimson Letter . St. Martin's Publishing

Group. Edizione del Kindle.

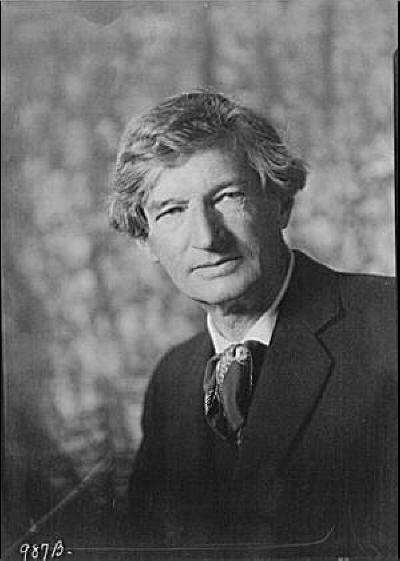

William

Bliss Carman FRSC (April 15, 1861 – June 8, 1929) was a Canadian poet who

lived most of his life in the United States, where he achieved international

fame. He was acclaimed as Canada's poet laureate[1]

during his later years.[2][3]

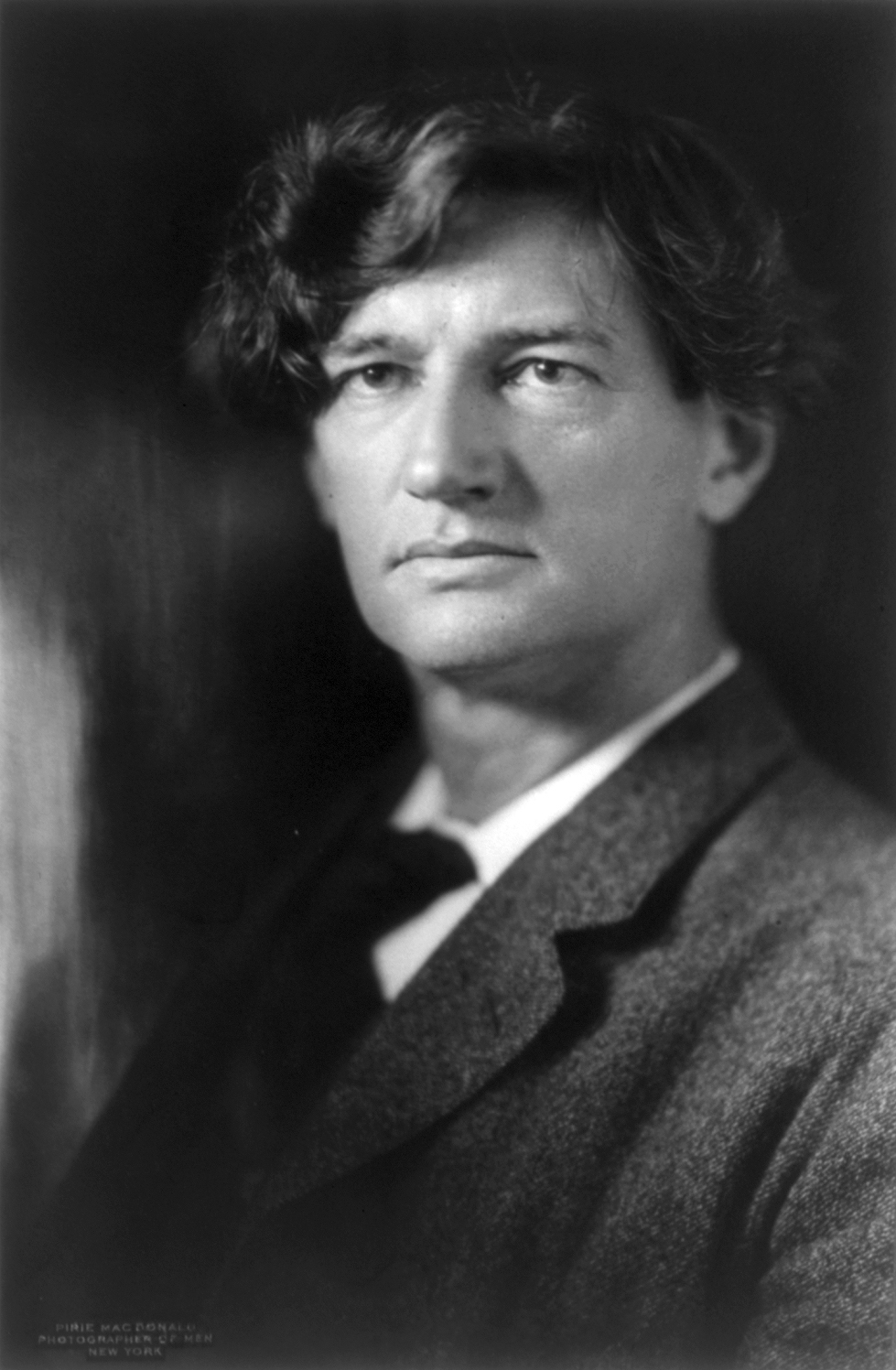

William

Bliss Carman FRSC (April 15, 1861 – June 8, 1929) was a Canadian poet who

lived most of his life in the United States, where he achieved international

fame. He was acclaimed as Canada's poet laureate[1]

during his later years.[2][3]