Queer Places:

1834 W 11th St, Los Angeles, CA 90006

Valhalla Memorial Park

North Hollywood, Los Angeles County, California, USA

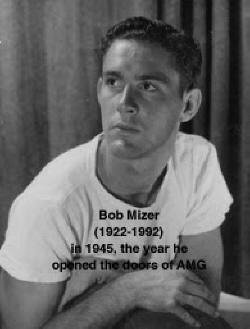

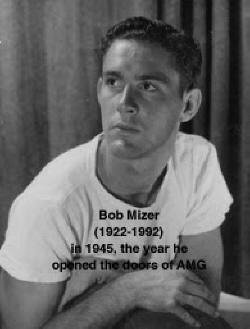

Most widely known as a photographer,

Robert "Bob" Henry Mizer (March 27, 1922 – May 12, 1992) was also a filmmaker and independent publisher. He set the standard for beefcake art. Mizer founded the Athletic Model Guild studio in 1945 when American censorship laws permitted women, but not men, to be photographed partially nude, so long as the result was “artistic” in nature.

Most widely known as a photographer,

Robert "Bob" Henry Mizer (March 27, 1922 – May 12, 1992) was also a filmmaker and independent publisher. He set the standard for beefcake art. Mizer founded the Athletic Model Guild studio in 1945 when American censorship laws permitted women, but not men, to be photographed partially nude, so long as the result was “artistic” in nature.

Robert Henry Mizer was born in Hailey, Idaho.

Attractive young men came to Los Angeles with the hope of Hollywood stardom. When the offers didn't materialize, many of them came to Bob Mizer's garage for a few dollars and a photo shoot that put them in the catalogue of the Athletic Models Guild. As his photographs and models became more and more popular, Mizer developed a trademark style that included projected backgrounds and lavish props. His mother,

Delia, and brother assisted his endeavors, and Mizer turned the family home into a haven for the young men he loved to photograph. After more than 20 years of work that showed no genitalia, he advanced to taking photographs of his models that displayed full frontal nudity, and sales skyrocketed. Even later he moved into hard-core content, and Mizer worked at his homoerotic craft every day until his death.

Mizer’s diaries, kept from the age of eight, make it clear that he was openly homosexual from his late teens, but until the age of 42 he lived and worked in his mother’s Los Angeles rooming house, where a strict ethical code prevented him from fully expressing his gay fantasies. For 24 years he worked in black and white and never showed a completely naked man, but following his mother’s death in 1964 Mizer plunged full force into the pleasures of male flesh, photographing fully nude men in explicit poses, often in psychedelically saturated colors.

/p>

In the 1970s and ’80s Bob Mizer’s compound, centered around the old rooming house, became home to dozens of his young models, who lived outdoors on couches and porch gliders among the chickens, geese, goats, monkeys, Roman statuary, cast off Christmas trees and other sundry props that featured in his increasingly quirky films and photography.

His career, however, had some serious bumps at the start. In 1947 he was wrongly accused of having sex with a minor and subsequently served a year-long prison sentence at a desert work camp in California. However, his career was catapulted into infamy in 1954 when he was convicted of the unlawful distribution of obscene material through the US mail. The items in question were a series of black and white photographs, taken by Mizer, of young bodybuilders wearing what were known as posing straps, a precursor to the G-string.

Upon his release from prison, Mizer continued working undeterred, founding the groundbreaking magazine Physique Pictorial in 1951, which also debuted the work of artists such as

Tom of Finland and

George Quaintance. This was America’s first male physique magazine, and certainly the gayest. Mizer's photographs were playful, tame images of young men posing, flexing, wrestling, and goofing off, while in states of near nudity. On the surface, they were marketed as physique materials, supposedly intended for bodybuilding and physical culture adherents, but they were really targeted toward for gay men, walking a fine line as to what was legally permissible.

Models included future Andy Warhol superstar

Joe Dallesandro and actors Glenn Corbett, Alan Ladd, Victor Mature. Throughout his long career Mizer produced a dizzying array of intimate and idiosyncratic imagery, some bereft of explicit content but bathed nevertheless in an unmistakable homoerotic aura, tributes to the varieties of desire. Mizer’s influence on artists ranging from

David Hockney (who moved from England to California in part to seek out Mizer),

Robert Mapplethorpe,

Francis Bacon,

Jack Smith, Andy Warhol and many others is only now beginning to be widely appreciated.

The bulk of the effects of Mizer's estate was unceremoniously thrown into a dumpster in 1992, after his death in Los Angeles. Fifty-year-old boxes of correspondence, studio props and personal artifacts from one of America’s most controversial artists were gone forever. Luckily the core of his life's work, consisting of about one million photographic negatives and thousands of 16mm films and videotapes, survived this irresponsible action and was boxed up and locked in storage for the next decade.

Bob Mizer’s mid-20th century photography helped shape the modern aesthetic and even some of the civil rights and censorship laws that we take for granted today. His classic images of muscled young men are reflected in today's advertising campaigns (Hollister, Abercrombie & Fitch), but in the 1940s, these types of photographs landed him in prison. Many Hollywood stars began their careers in Mizer’s studio, including sword-n-sandal film star Ed Fury, Glenn Corbett of Route 66, Andy Warhol’s protege Joe Dallesandro, and even former governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger.

His work mirrored our nation’s popular culture at the moment. Images of young hoodlums in leather jackets sneered across his photographs as

Marlon Brando and

James Dean brawled on the big screen. Mizer’s Greek statues and Roman gladiators mimicked the ancient world as Charlton Heston reigned on the screen in Ben-Hur. It was all very kitschy and delicious fun.

The 1999 film “Beefcake” chronicled Mizer’s life and work.

This 93-minute docu-drama pays homage to the muscle magazines of the 1940s, '50s, and '60s – in particular, Physique Pictorial magazine, published by Bob Mizer of the Athletic Model Guild. It was inspired by a picture book by F. Valentine Hooven III (pub. by Taschen) and was directed by Thom Fitzgerald. The film features pastiche recreations of life at the Athletic Model Guild, mixed with interviews with models and photographers whose work actually appeared in the early magazines, including Jack LaLanne and Joe Dallesandro.

In 2003, through a series of fortunate mishaps, photographer and filmmaker Dennis Bell made the decision to keep Mizer’s work together by acquiring the remainder of the estate from a storage locker. This occurred just days before the contents were slated to be completely split apart and sold off piecemeal, which would have removed this material from the public eye forever. Bell founded the non-profit Bob Mizer Foundation and has become the new guardian of Mizer’s work.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

Most widely known as a photographer,

Robert "Bob" Henry Mizer (March 27, 1922 – May 12, 1992) was also a filmmaker and independent publisher. He set the standard for beefcake art. Mizer founded the Athletic Model Guild studio in 1945 when American censorship laws permitted women, but not men, to be photographed partially nude, so long as the result was “artistic” in nature.

Most widely known as a photographer,

Robert "Bob" Henry Mizer (March 27, 1922 – May 12, 1992) was also a filmmaker and independent publisher. He set the standard for beefcake art. Mizer founded the Athletic Model Guild studio in 1945 when American censorship laws permitted women, but not men, to be photographed partially nude, so long as the result was “artistic” in nature.