Partner Adeline Knapp

Queer Places:

673 Grove St, San Francisco, CA 94102

625 W 136th St, New York, NY 10031

Lathrop Manor Bed & Breakfast, 380 Washington St, Norwich, CT 06360

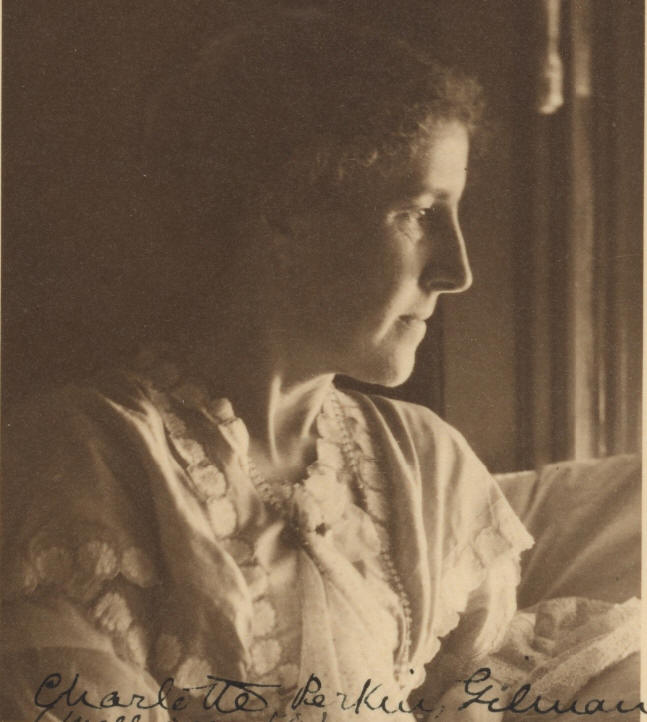

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, also Charlotte Perkins Stetson, (July 3, 1860 –

August 17, 1935), was a prominent American feminist, sociologist, novelist,

writer of short stories, poetry, and nonfiction, and a lecturer for social

reform. She was a member of the Heterodoxy Club.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman fantasized about the newspaper headlines that might

result from the discovery of her love letters to the journalist and reformer

Adeline Knapp: ‘Mrs. Stetson’s Love Affair with a Woman’.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, also Charlotte Perkins Stetson, (July 3, 1860 –

August 17, 1935), was a prominent American feminist, sociologist, novelist,

writer of short stories, poetry, and nonfiction, and a lecturer for social

reform. She was a member of the Heterodoxy Club.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman fantasized about the newspaper headlines that might

result from the discovery of her love letters to the journalist and reformer

Adeline Knapp: ‘Mrs. Stetson’s Love Affair with a Woman’.

Gilman was a utopian feminist and served as a role model for future generations of feminists because of her unorthodox concepts and lifestyle. Her best remembered work today is her semi-autobiographical short story "The Yellow Wallpaper" which she wrote after a severe bout of postpartum psychosis.

Gilman was born on July 3, 1860 in Hartford, Connecticut, to Mary Perkins (formerly Mary Fitch Westcott) and Frederic Beecher Perkins. She had only one brother, Thomas Adie, who was fourteen months older, because a physician advised Mary Perkins that she might die if she bore other children. During Charlotte's infancy, her father moved out and abandoned his wife and children, leaving them in an impoverished state.[1] Since their mother was unable to support the family on her own, the Perkins were often in the presence of her father's aunts, namely Isabella Beecher Hooker, a suffragist, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin, and Catharine Beecher, educationalist.

Her schooling was erratic: she attended seven different schools, for a cumulative total of just four years, ending when she was fifteen. Her mother was not affectionate with her children. To keep them from getting hurt as she had been, she forbade her children to make strong friendships or read fiction. In her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Gilman wrote that her mother showed affection only when she thought her young daughter was asleep.[2] Although she lived a childhood of isolated, impoverished loneliness, she unknowingly prepared herself for the life that lay ahead by frequently visiting the public library and studying ancient civilizations on her own. Additionally, her father's love for literature influenced her, and years later he contacted her with a list of books he felt would be worthwhile for her to read.[3]

Much of Gilman's youth was spent in Providence, Rhode Island. What friends she had were mainly male, and she was unashamed, for her time, to call herself a "tomboy."[4]

Her natural intelligence and breadth of knowledge always impressed her teachers, who were nonetheless disappointed in her because she was a poor student.[5] Her favorite subject was "natural philosophy," especially what later would become known as physics. In 1878, the eighteen-year-old enrolled in classes at the Rhode Island School of Design with the monetary help of her absent father,[6] and subsequently supported herself as an artist of trade cards. She was a tutor, and encouraged others to expand their artistic creativity.[7] She was also a painter.

In 1884, she married the artist Charles Walter Stetson, after initially declining his proposal because a gut feeling told her it was not the right thing for her.[8] Their only child, Katharine Beecher Stetson, was born the following year. Charlotte Perkins Gilman suffered a very serious bout of post-partum depression. This was an age in which women were seen as "hysterical" and "nervous" beings; thus, when a woman claimed to be seriously ill after giving birth, her claims were sometimes dismissed.[9]

In 1888, Charlotte separated from her husband – a rare occurrence in the late nineteenth century. The two divorced in 1894.[10] Following the separation, Charlotte moved with her daughter to Pasadena, California, where she became active in several feminist and reformist organizations such as the Pacific Coast Women's Press Association, the Woman's Alliance, the Economic Club, the Ebell Society (a women's club named after Adrian John Ebell), the Parents Association, and the State Council of Women, in addition to writing and editing the Bulletin, a journal put out by one of the earlier-mentioned organizations.[11]

During the year she left her husband, Charlotte met Adeline Knapp, called "Delle". Cynthia J. Davis describes how the two women had a serious relationship. She writes that Gilman "believed that in Delle she had found a way to combine loving and living, and that with a woman as life mate she might more easily uphold that combination than she would in a conventional heterosexual marriage." The relationship ultimately came to an end.[13][14]

In 1894, Gilman sent her daughter east to live with her former husband and his second wife, her friend Grace Ellery Channing. Gilman reported in her memoir that she was happy for the couple, since Katharine's "second mother was fully as good as the first, [and perhaps] better in some ways."[12] Gilman also held progressive views about paternal rights and acknowledged that her ex-husband "had a right to some of [Katharine's] society" and that Katharine "had a right to know and love her father."[13]

After her mother died in 1893, Gilman decided to move back east for the first time in eight years. She contacted George Houghton Gilman, her first cousin, whom she had not seen in roughly fifteen years, who was a Wall Street attorney. They began spending a significant amount of time together almost immediately and became romantically involved. While she would go on lecture tours, Houghton and Charlotte would exchange letters and spend as much time as they could together before she left. In her diaries, she describes him as being "pleasurable" and it is clear that she was deeply interested in him.[14] From their wedding in 1900 until 1922, they lived in New York City at 625 West 136th Street. Their marriage was nothing like her first one.

Dr Alice Hamilton, an expert in occupational health and a leading pacifist campaigner, met Charlotte in Chicago in the winter of 1898, noting in a letter to her sister that ‘Mrs. Stetson … is very attractive. She is the woman … who couldn’t stand being married … and now is on excellent terms with her former husband and his present wife, who takes care of Mrs. Stetson’s little girl, an arrangement which I fancy I should approve of.’

In 1922, Gilman moved from New York to Houghton's old homestead in Norwich, Connecticut. Following Houghton's sudden death from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1934, Gilman moved back to Pasadena, California, where her daughter lived.[15]

In January 1932, Gilman was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer.[16] An advocate of euthanasia for the terminally ill, Gilman committed suicide on August 17, 1935 by taking an overdose of chloroform. In both her autobiography and suicide note, she wrote that she "chose chloroform over cancer" and she died quickly and quietly.[17]

My published books: