Partner John Powell

Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Columbia University (Ivy League), 116th St and Broadway, New York, NY 10027

Mount Auburn Cemetery

Cambridge, Middlesex County, Massachusetts, USA

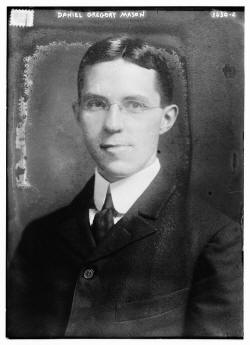

Daniel

Gregory Mason (November 20, 1873 – December 4, 1953) was an

American

composer and

music critic. His longtime companion was Virginian composer and pianist

John Powell (1882-1963).

Pierre de Chaignon la Rose’s set,

whose life centered on rooms in Matthews Hall that he shared with Daniel

Gregory Mason, could hardly have escaped notice as

boldly bohemian, and it included a wide range of types that showed the same

diversity of the Wildean and Whitmanic observable in The Cult of the Purple

Rose itself.

Daniel

Gregory Mason (November 20, 1873 – December 4, 1953) was an

American

composer and

music critic. His longtime companion was Virginian composer and pianist

John Powell (1882-1963).

Pierre de Chaignon la Rose’s set,

whose life centered on rooms in Matthews Hall that he shared with Daniel

Gregory Mason, could hardly have escaped notice as

boldly bohemian, and it included a wide range of types that showed the same

diversity of the Wildean and Whitmanic observable in The Cult of the Purple

Rose itself.

Mason was born in Brookline, Massachusetts. He came from a long line of notable American musicians, including his father Henry Mason, and his grandfather Lowell Mason. His cousin, John B. Mason, was a popular actor on the American and British stage. Daniel Mason studied under John Knowles Paine at Harvard University from 1891 to 1895, continuing his studies with George Chadwick and Percy Goetschius. He also studied with Arthur Whiting and later wrote a biographical journal article about him.[1] In 1894 he published his Opus 1, a set of keyboard waltzes, but soon after began writing about music as his primary career. He became a lecturer at Columbia University in 1905, where he would remain until his retirement in 1942, successively being awarded the positions of assistant professor (1910), MacDowell professor (1929) and head of the music department (1929-1940). He was elected a member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia fraternity, the national fraternity for men in music, in 1914 by the Fraternity's Alpha chapter at the New England Conservatory in Boston.

After 1907, Mason began devoting significant time to composition, studying with Vincent D'Indy in Paris in 1913, garnering numerous honorary doctorates and winning prizes from the Society for the Publication of American Music and the Juilliard Foundation.

He died in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Mason's compositional idiom was thoroughly romantic. He deeply admired and respected the Austro-Germanic canon of the nineteenth century, especially Brahms; despite studying under D'Indy, he disliked impressionism and utterly disregarded the modernist musical movements of the 20th century. Mason sought to increase respect for American music, sometimes incorporating indigenous and popular motifs (such as popular songs or Negro spirituals) into his scores or evoking them through suggestive titles, though he was not a thorough-going nationalist. He was a fastidious composer who repeatedly revised his scores (the manuscripts of which are now held at Columbia).

Mason wrote or co-wrote eighteen books on music, including an autobiography and a number of music appreciation works written for a general audience. His analyses of the chamber music of Brahms and Beethoven have been recognized as insightful. In his more polemical works, he attacked modern music, urged American composers to stop imitating Continental models and find an individual style, and criticized European conductors in America (such as Toscanini) for rarely including American works in their programs.

My published books: