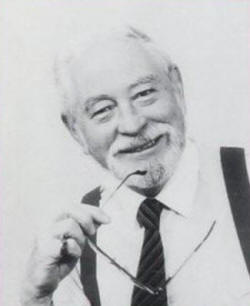

Partner Felix Brenner

Queer Places:

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

2 Callow St, London SW3 6BE, UK

64 Woodlands, Overton, Hampshire

David Herbert Shipman (4 November 1932 – 22 April 1996)[1] was an English film critic and writer best known for his book trilogy The Great Movie Stars and his book duology The Story of Cinema. He was described in an obituary as "the most influential writer on film in the world".[1] In 1964 he met the art director and editor Felix Brenner, and together in Chelsea and at their cottage retreat in Hampshire they made a formidable partnership.

David Herbert Shipman (4 November 1932 – 22 April 1996)[1] was an English film critic and writer best known for his book trilogy The Great Movie Stars and his book duology The Story of Cinema. He was described in an obituary as "the most influential writer on film in the world".[1] In 1964 he met the art director and editor Felix Brenner, and together in Chelsea and at their cottage retreat in Hampshire they made a formidable partnership.

David Herbert Shipman was born on 4 November 1932 at Lyndale, Waldemar Avenue, Upper Hellesdon, Norwich, the younger child and only son of Alfred Herbert Shipman (1898–1981), a commercial traveller in electrical appliances, and Ethel May Deakes (1903–1988), clerical worker and daughter of a piano-tuner. Both parents were Londoners, and the family moved back to the capital, to Eltham, in 1940, only for the children to be evacuated in the following year to Pensilva, Cornwall. David was educated variously at primary schools in London, then, on a junior county scholarship, at Callington county school, Cornwall, where he spent 'some of the happiest years of my life' (Shipman). With the end of the Second World War he went to Shooters Hill grammar school, which he left in 1949, aged sixteen, after taking his school certificate, to become a clerk in the architects' office of the London county council.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), seen on holiday in Great Yarmouth when he was five, was the film that ignited Shipman's cine-enthusiasm, but he might have been condemned to the 'sheer boredom' (Shipman) of town-planning paper pushing had it not been for national service. In 1951, against his will, he joined the RAF, on the clerical side, and in its democratic conviviality discovered a self-confidence that he never, despite many buffets and supposed buffets, entirely lost. The following year he spent in Singapore, in Changi, where an RAF chaplain, the Revd James Tinline, introduced him to the films of Greta Garbo and the Marx brothers, and persuaded him to take three A-levels and try for Oxford University. Shipman went up to Merton College in 1954 to read English and, although he failed his first-year preliminary examination twice and was sent down after only one year, he enjoyed himself thoroughly. He acted and sat on the Film Society committee, he fell in love with Judy Garland, and he had found a way out.

For the next ten years Shipman worked as a publisher's representative, first on staff, for Victor Gollancz, Methuen, and the Curtis Publishing Company, and after 1963 as a freelance, for Paul Hamlyn, Hale, and Panther. His favourite years were from 1961 to 1963, when he lived in Paris for Curtis, acting as European representative for Bantam Books, and travelled the continent, returning, sometimes just for a night, to London for performances at the National Film Theatre. In 1962 he started contributing to the magazine Films and Filming. In December 1964 he met Felix Otto Brenner (born 1923), the New York-born art director of Hamlyn, who was to be his partner for the rest of his life. He moved into Brenner's London flat, at 2 Callow Street, Chelsea, in March 1965, and in September he gave up travelling.

In 1968 he began his most popular book, the first volume of The Great Movie Stars, The Golden Years, and it became a best-seller on its publication in 1970. Two years later a second volume appeared, The International Years, drawing on the interest in non-Hollywood film that Shipman had developed during his time living in Paris. That same year he was commissioned by Phaidon to write a companion volume to Ernst Gombrich's The Story of Art. "I thought it would take me two years and it took 11, because I needed to see the 5,000 films discussed in it," he later wrote, determined that he would never write about a film unless he had himself seen it.

The massive two-volume work - some half a million words - was eventually published by Hodder & Stoughton with a preface by Ingmar Bergman. It was the book of which he (and his publisher) was most proud, and was a beguiling mixture of the authoritative and the idiosyncratic. Of Alfred Hitchcock, for instance, Shipman wrote: "I find almost all of his later films lumbering, literal and not nearly as clever in evoking thrills as they think they are." He described as "unequivocally the greatest film ever made" the Japanese three-parter The Human Condition (1959-61), directed by Masaki Kobayashi - while admitting that it was also the longest film ever shown.

Shipman said of himself that he was the only British film historian to make a living solely from books, and in the 1980s several shorter books helped him through what, financially, were difficult years: a short biography of Marlon Brando and studies of science fiction and sex and eroticism in the cinema. He also wrote a film and video guide entirely from his own experience, an extraordinary achievement when in 1995 alone some 419 new films were screened; and all his reference books he vigorously updated. A third volume of The Great Movie Stars, The Independent Years, appeared in 1991, by which time he was in much demand as lecturer, journalist and film consultant. He was a frequent adviser to the National Film Theatre, and in 1986 began writing obituaries for the Independent, becom-ing one of its most regular contributors.

In 1992 Shipman's biography Judy Garland appeared, to widespread acclaim. It showed he could write as well at length on a single individual as he could in brief in his works of reference. At the time of his death he was completing what promised to be an ambitious biography of Fred Astaire, and he was full of other plans, including a memoir of the screenwriter and director Joseph Mankiewicz.

Joe Mankiewicz and his wife Rosemary were just two of a number of Hollywood celebrities who became close friends. Sheila Grahame was another who would be a regular visitor at Shipman's stylish flat in Callow Street, in the heart of Chelsea. Shipman himself was a shy man, exceptionally kind while sensitive to criticism and watchful of his reputation. His exhaustive research methods and the lack of any regular means of income meant that he was never rich; but he was always sartorially elegant, and in his last public outing, attending the publication party for Kevin Brownlow's biography of David Lean (the appearance of which was due much to Shipman's influence), was dressed in a three-piece Savile Row suit and accompanying trilby.

Davd Shipman died in his sleep of a heart attack at home, in the house that had been his mother's, 64 Woodlands, Overton, Hampshire, on 22 April 1996. He was cremated at Aldershot crematorium on 2 May.

The world of film has lost not only one of its foremost champions and historians, but a man whose genial presence, warmth, generosity and boundless enthusiasm will be sorely missed by all who knew him, writes Tom Vallance.

A handsome man with, in recent years, a flock of white hair, David was always ready with a beaming smile and effusive greeting, his eyes twinkling as he disclosed some new piece of movie information or gossip. A man of strong opinions, he nonetheless showed genuine concern if one disagreed with his views, and would listen carefully to one's reasons. Unlike many historians, he refused to write critically of any film he had not personally seen, so, although his sometimes controversial judgements could raise hackles, at least they were his own opinions and not regurgitated from the writings of others.

He started keeping notes on the films he had seen when he was in his early teens and carried on throughout his life, compiling an enormous library of personal synopses and critical comments with which, like everything else, he was extremely generous. One had only to mention an obscure German silent recorded from satellite television and next morning's post would bring a copy of his detailed notes to aid one's viewing.

His The Good Film and Video Guide (first published in 1984) is notable for its inclusion of more detail and more foreign films than similar publications, and he was particularly proud of his giant opus the two- volume The Story of Cinema. It is a monumental achievement to be sure, distinguished by the diligent research and meticulous documentation that marks all his work, but his most important contribution to film literature may well be his wonderful trilogy The Great Movie Stars.

Unlike previous such reference books, which included a brief biography, then a (usually incomplete) list of credits, his pioneered the chronological career-filmography, contextualising the films so that one could chart the trajectory of each star, the changes in course and their fluctuating fortunes. It was an original idea, triumphantly followed through, and won instant acclaim from critics and public ("The best, and best-written, aide-memoire on the great stars," wrote Clive Hirschhorn). Consistent sellers, the three books are permanently in print, and there can be few film enthusiasts who do not have them on their shelves.

All of David Shipman's work was pervaded by his unquenchable love of cinema. When I last saw him, four days before his death, he was as enthusiastic as ever at the prospect of fresh films, both old and new, to be viewed over the coming days.

In the nine-and-a-half-year history of the Independent, David Shipman contributed more than 200 obituaries to the newspaper, most of them written on the run, writes James Fergusson. He was encyclopaedic, enthusiastic, fiercely loyal.

He could also be quite difficult. Sometimes his fastidiousness and high standards dictated a de-haut-en-bas style which might sit well on the experienced film critic he was but would not look so judicious in the sober light of the posthumous morning. As the editor of his obituaries one had to wrestle with him to persuade him of this, to recast and to rethink, to steer him towards a candour the right side of kindness. He endured such bouts stoically, and bounced straight back. His enthusiasm was real and invigorating.

Shipman embraced the ideals of the new newspaper - and particularly the liberations of its obituaries column - from the start. A former Daily Telegraph obituaries editor, in introducing an amusing anthology of that newspaper's obituaries, has boasted that it was the Telegraph which initiated the innovations to the obituary form which have revived it, across all newspapers, for the Nineties. Shipman would snort at this, properly, for it was the facility the Independent afforded for signed pieces, written accountably and with a personal authority by such contributors as David Shipman, in the style of an essay or a profile, and boldly illustrated (in Shipman's case with vivid Hollywood studio portraits and film-stills), which drew a new and young readership to the newspaper obituary. The Independent sought to demystify obituaries, to make them not so much a hilarious private joke as honest, catholic, authoritative, accessible.

David Shipman's last obituary, of Toms Gutierrez Alea, the Cuban director, producer and screenwriter, appeared the Thursday before Shipman's own death. His first, published on 16 October 1986, was of Keenan Wynn, "one of the last great character men, . . . with a licence to steal scenes from Garland or Gable, putting them down, putting up with them, moustache atwitch to whack his lines across before the camera returned to making them look good". The words could almost describe Shipman himself.

My published books: