Queer Places:

39 Royal Ave, Chelsea, London SW3 4QE, UK

Golders Green Crematorium

Golders Green, London Borough of Barnet, Greater London, England

Elinor Glyn (née Sutherland; 17 October 1864 – 23 September 1943) was a British novelist and scriptwriter who specialised in romantic fiction, which was considered scandalous for its time, although her works are relatively tame by modern standards. She popularized the concept of the It-girl, and had tremendous influence on early 20th-century popular culture and, possibly, on the careers of notable Hollywood stars such as

Rudolph Valentino, Gloria Swanson and, especially,

Clara Bow.

Elinor Glyn (née Sutherland; 17 October 1864 – 23 September 1943) was a British novelist and scriptwriter who specialised in romantic fiction, which was considered scandalous for its time, although her works are relatively tame by modern standards. She popularized the concept of the It-girl, and had tremendous influence on early 20th-century popular culture and, possibly, on the careers of notable Hollywood stars such as

Rudolph Valentino, Gloria Swanson and, especially,

Clara Bow.

Elinor Sutherland was born on 17 October 1864 in Saint Helier, Jersey, in the Channel Islands. She was the younger daughter of Douglas Sutherland (1838–1865), a civil engineer of Scottish descent, and his wife Elinor Saunders (1841–1937), of an Anglo-French family that had settled in Canada. Her father was said to be related to the Lords Duffus.[1][2]

Her father died when she was two months old; her mother returned to the parental home in Guelph, in what was then Upper Canada, British North America (now Ontario) with her two daughters.[3] Here, young Elinor was taught by her grandmother, Lucy Anne Saunders (née Willcocks), daughter of Sir Richard Willcocks, a magistrate in the early Irish police force, who helped to suppress the Emmet Rising in 1803.[4][5] Richard's brother Joseph also settled in Upper Canada, publishing one of the first opposition papers there, pursuing liberty, and dying a rebel in 1814. The Anglo-Irish grandmother instructed young Elinor in the ways of upper-class society. This training not only gave her an entrée into aristocratic circles on her return to Europe, it also led her reputation as an authority on style and breeding when she worked in Hollywood in the 1920s. Her grandfather on her mother's side, Thomas Saunders (1795-1873) was a direct descendant of the Saunders family who had possessed Pitchcott Manor in Buckinghamshire for several centuries.[6]

The family lived in Guelph for seven years at a stone home that still stands near the University of Guelph.[3] By 1872, their mother had remarried and took the sisters back to Britain. They were preteens at the time and years later, would build their careers in the United States. Glyn's elder sister grew up to be Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, famous as a fashion designer under the name Lucile.[7] Glyn's mother remarried in 1871 to David Kennedy, and the family returned to Jersey when Glyn was about eight years old.[8] Her subsequent education at her stepfather's house was by governesses.[9]

At the age of 28, the green-eyed, red-haired but dowryless Elinor married on 27 April 1892. Her husband was Clayton Louis Glyn (13 July 1857 – 10 November 1915), a wealthy but spendthrift barrister and Essex landowner who was descended from Sir Richard Carr Glyn, an 18th-century Lord Mayor of London.[10] The couple had two daughters, Margot and Juliet, but the marriage foundered on mutual incompatibility.

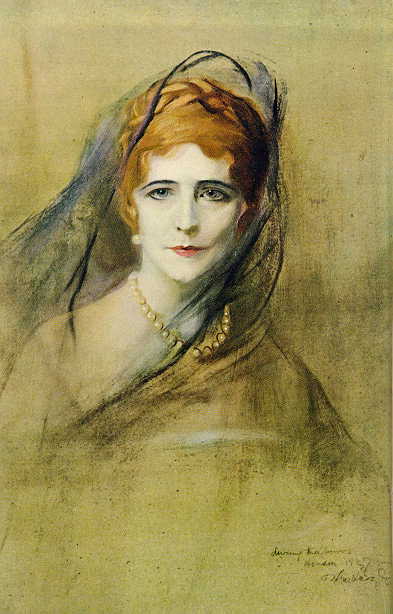

Glyn began writing in 1900, starting with Visits of Elizabeth, a book based on letters to her mother, although in her memoirs Lady Angela Forbes says that Glyn used her as the prototype of Elizabeth.[11] Her marriage was troubled, and Glyn began having affairs with various British aristocrats. Her Three Weeks, about an exotic Balkan queen who seduces a young British aristocrat, was allegedly inspired by her affair with 16-years junior Lord Alistair Innes Ker, brother of the Duke of Roxburghe, and it scandalized Edwardian society.[12] She had a long affair between circa 1907 and 1916 with George Curzon.[13] She was famously painted by society painter Philip de László at the age of 48.[14]

As her husband fell into debt from around 1908, Glyn wrote at least one novel a year to keep up her standard of living. Her husband died in November 1915, aged 58, after several years of illness.

Elinor Glyn 1912

Philip Alexius de Laszlo -- British painter (1869-1937)

1912

Elinor Glyn

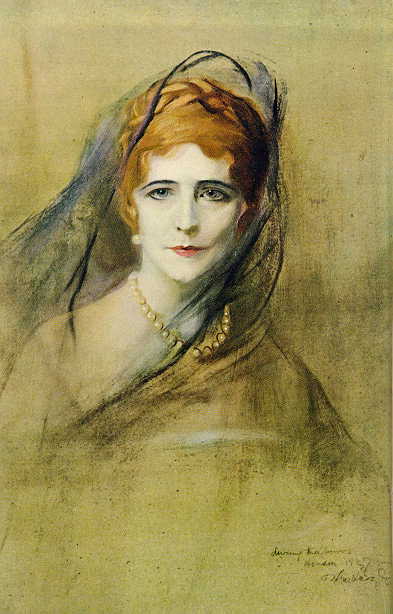

Philip Alexius de Laszlo -- British painter (1869-1937)

1927

Preparatory Sketch of a Lady

(Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon)

1913

Private Collection

Oil on Canvas board

16 x 13 in. (40.6 x 33 cm.)

Signed, dated and inscribed l.l. P. A. de László / 1913 London

Glyn pioneered risqué, and sometimes erotic, romantic fiction aimed at a female readership, a radical idea for its time—though her writing is not scandalous by modern standards. She coined the use of the word it to mean a characteristic that "...draws all others with magnetic force. With 'IT' you win all men if you are a woman–and all women if you are a man. 'IT' can be a quality of the mind as well as a physical attraction."[16] Her use of the word is often erroneously taken to be a euphemism for sexuality or sex appeal.[17]

In 1919 she signed a contract with William Randolph Hearst's International Magazine Company for stories and articles that included a clause for the motion picture rights.[18] She was brought over from England to write screenplays by the Famous Players-Lasky Production Company.[19] She wrote for Cosmopolitan and other Hearst press titles, advising women on how to keep their men and imparting health and beauty tips. The Elinor Glyn System of Writing (1922) gives insights into writing for Hollywood studios and magazine editors of the time.[20]

From the 1927 novel, "It": "To have 'It', the fortunate possessor must have that strange magnetism which attracts both sexes.... In the animal world 'It' demonstrates in tigers and cats—both animals being fascinating and mysterious, and quite unbiddable." From the 1927 movie, "It": "self-confidence and indifference as to whether you are pleasing or not".[21] Glyn was the celebrated author of such early 20th-century bestsellers as "It",[22] Three Weeks,[23] Beyond the Rocks[24] and other novels that were quite racy for the time. The screenplay of the novel It helped Glyn gain popularity as a screenwriter. However, she is only credited as an author, adapter, and co-producer on the project. She also made a cameo appearance in the film.[19]

On the strength of the popularity and notoriety of her books, Glyn moved to Hollywood to work in the movie industry in 1920. She was one of the most famous women screenwriters in the 1920s. She has 28 story or screenwriting credits, three producing credits, and two credits for directing.[25] Her first script was called The Great Moment and starred Gloria Swanson. She is credited[who?] with the re-styling of Swanson from giggly starlet to elegant star. The duo connected again when Beyond the Rocks was made into a silent film that was released in 1922; the Sam Wood-directed film stars Gloria Swanson and Rudolph Valentino as a romantic pair. In 1927, Glyn helped to make a star of actress Clara Bow, for whom she coined the sobriquet "the It girl". In 1928, Bow also starred in Red Hair, which was based on Glyn's 1905 novel.

Apart from being a scriptwriter for the silent movie industry, working for both MGM and Paramount Pictures in Hollywood in the mid-1920s, she had a brief career as one of the earliest female directors.[26] Her family established a company in 1924, Elinor Glyn Ltd, to which she signed her copyrights receiving an income from the firm and an annuity in later life. The firm was an early pioneer of cross-media branding.[27]

Glyn was responsible for many screenplays in the 1920s that included Six Hours (1923). Three Weeks (1924) was one of her most famous pieces about a Queen in a struggling marriage who while on vacation has a three-week affair with a man.[25] In addition to that, His Hour (1924), which was directed by King Vidor, Love's Blindness (1926), a movie about a marriage that is done strictly for financial reasons only, Man and Maid (1925), about a man who must choose between two different women, The Only Thing (1925), Ritzy (1927), Red Hair (1928), which was a comedy vehicle to demonstrate the passion of red-haired people, and The Price of Things (1930). Three screenplays based on Glyn's novels and a story in the mid to late twenties, Man and Maid, The Only Thing, and Ritzy did not do well at the box office, despite the success Glyn gained with her first project, The Great Moment, which was in the same genre.[25] In 1930 she wrote her first non-silent film, Such Men Are Dangerous, her last screenplay in the United States.[25]

Glyn returned home to England in 1929 in part because of tax demands. With her return she set out to form her own production company, Elinor Glyn Ltd. After she started the company, she began working as a film director as well. Paying out of her own pocket, she directed Knowing Men in 1930, which showed a more traditionalist view of men as sexual harassers. The project was a disaster, and the screenwriter Edward Knoblock sued Glyn so that the work could not be released. Elinor Glyn Ltd produced a second film in 1930, The Price of Things, which was also unsuccessful and was never released in the US. As her company failed and she exhausted her finances, Glyn decided to retire from film work and instead focus on her first passion, writing novels.[19]

After a short illness, Glyn died on 23 September 1943, at 39 Royal Avenue, Chelsea, London, aged 78,[28] and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium.[29] Her ashes lie above the door to the Jewish Shrine at the west end of the columbarium.

She was survived by two daughters. Her elder daughter Margot Elinor, Lady Davson OBE married Sir Edward Davson, 1st Baronet (14 September 1875 – 9 August 1937) in 1921 and had two sons: Geoffrey Leo Simon Davson, who inherited his father's baronetcy (created in 1927) but changed his name to Anthony Glyn (13 March 1922 – 20 January 1998), and Christopher Davson. Margot Elinor died on 10 September 1966 in Rome.[30]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

Elinor Glyn (née Sutherland; 17 October 1864 – 23 September 1943) was a British novelist and scriptwriter who specialised in romantic fiction, which was considered scandalous for its time, although her works are relatively tame by modern standards. She popularized the concept of the It-girl, and had tremendous influence on early 20th-century popular culture and, possibly, on the careers of notable Hollywood stars such as

Rudolph Valentino, Gloria Swanson and, especially,

Clara Bow.

Elinor Glyn (née Sutherland; 17 October 1864 – 23 September 1943) was a British novelist and scriptwriter who specialised in romantic fiction, which was considered scandalous for its time, although her works are relatively tame by modern standards. She popularized the concept of the It-girl, and had tremendous influence on early 20th-century popular culture and, possibly, on the careers of notable Hollywood stars such as

Rudolph Valentino, Gloria Swanson and, especially,

Clara Bow.