Partner Ralph Wormleighton

Queer Places:

Spadina Rd, Toronto, ON, Canada

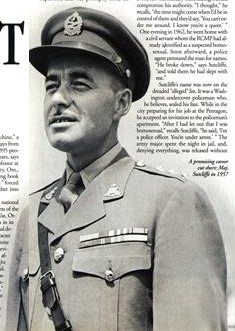

Herbert Sutcliffe (1917 - August 17, 2003) was a history teacher and decorated World War II veteran - awarded the Member of the Order of the British Empire for bringing his troops back from behind enemy lines at Calais, France, in 1944. While a 24-year-old lance-corporal posted to Britain, he had his first sexual encounter - with a Canadian Army sergeant - on New Year's Eve, 1941. As he moved through the ranks, he took care to avoid sex with military men, fearing it could compromise his authority.

Herbert Sutcliffe (1917 - August 17, 2003) was a history teacher and decorated World War II veteran - awarded the Member of the Order of the British Empire for bringing his troops back from behind enemy lines at Calais, France, in 1944. While a 24-year-old lance-corporal posted to Britain, he had his first sexual encounter - with a Canadian Army sergeant - on New Year's Eve, 1941. As he moved through the ranks, he took care to avoid sex with military men, fearing it could compromise his authority.

Afterward, he returned to his home town to pursue a history degree from the University of Toronto. But in 1950, he passed up graduate school at Yale in order to make the military his professional life. After rising through the ranks for the next dozen years, the ground beneath him fell away on June 1, 1962, leaving his career and personal life in shambles.

On the eve of being transferred to a new post at the Pentagon, he was discharged in 1962 for being gay, one of nearly 400 people who lost their jobs as the result of a 1959-1968 Canadian investigation to weed out homosexuals in the military and civil service because they were deemed national security threats.

Sutcliffe was in Ottawa that day readying himself for a prestigious post at the Pentagon in Washington when his commanding officer delivered the blow: the army had confirmed that he was a homosexual and, on that basis, was discharging him. Shocked and scared, Sutcliffe went home, had a drink and contemplated suicide.

Despite his feelings of isolation, Sutcliffe was not alone in his misfortune. Between 1959 and 1968, the Security Panel - a committee of RCMP officers and representatives from the Privy Council, National Defence and External Affairs - investigated 9,000 men and women suspected of homosexuality. The panel targeted the civil service, the military and the Mounties, spending millions of dollars in the process -- some of them on such bizarre measures as the "fruit machine," a device designed to differentiate gays from straights. Like Sutcliffe, at least 395 people lost their jobs.

Still angry: Herbert Sutcliffe, left, in the Spadina Rd. apartment he shares with Ralph Wormleighton, shows his companion the medals he won for service during World War II before he was exposed as a homosexual and his military career shattered. His anger has not dimmed.

After being drummed out of the military, he returned to Toronto and enrolled in teacher's college, later landing a job teaching history in a high school. In this, he sees more than a little irony: "The military had thrown me out because I'm a homosexual, and here I am teaching 18-, 19-, 20-year-old males." In his post-army life, Sutcliffe chose to keep his sexuality private until he retired in 1979. Finally, he says, "I reached the point where I wouldn't apologize for being gay. That's the way I am, and I'm comfortable with it."

When same-sex marriage became legal in Ontario, Herbert Sutcliffe and Ralph Wormleighton, his partner of 30 years, didn't rush to the altar. "We didn't see any point in our doing it. In terms of income tax, we were already regarded as a couple, and our wills and powers-of-attorney were drawn up to reflect that."

My published books: