Queer Places:

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

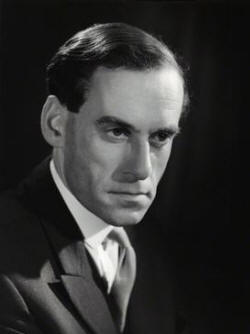

John Jeremy Thorpe (29 April 1929 – 4 December 2014) was a British politician who served as the Member of Parliament for North Devon from 1959 to 1979, and as leader of the Liberal Party from 1967 to 1976. In May 1979 he was tried at the Old Bailey on charges of conspiracy and incitement to murder his ex-boyfriend

Norman Scott, a former model. Thorpe was acquitted on all charges, but the case, and the furore surrounding it, ended his political career.

According to Michael Bloch's biography of the politician,

David Carritt had an affair with Jeremy Thorpe in the late 1950s.[12]

John Jeremy Thorpe (29 April 1929 – 4 December 2014) was a British politician who served as the Member of Parliament for North Devon from 1959 to 1979, and as leader of the Liberal Party from 1967 to 1976. In May 1979 he was tried at the Old Bailey on charges of conspiracy and incitement to murder his ex-boyfriend

Norman Scott, a former model. Thorpe was acquitted on all charges, but the case, and the furore surrounding it, ended his political career.

According to Michael Bloch's biography of the politician,

David Carritt had an affair with Jeremy Thorpe in the late 1950s.[12]

The political journalist Andrew Rawnsley described Thorpe as a "dandy, exhibitionist, superb showman, shallow thinker, wit and mimic, cunning opportunist, sinister intriguer, idealistic internationalist and a man with a clandestine homosexual life".[215] Thorpe never discussed his sexuality publicly, although throughout his political career he led a double life—responsible politician by day while, according to Douglas Murray, "by night he was not only very gay but rather carefree about being so."[210] The writer and broadcaster Jonathan Fryer, who was a gay activist within the Liberal Party in the 1970s, maintained that in the repressive climate of the time Thorpe "couldn't have come out, even if he'd wanted to". His double standard irritated and alienated the gay Liberals: "He wanted the best of both worlds—his fun and a family."[216] In his review of Michael Bloch's biography, Murray writes: "Jeremy Thorpe had hoped to be remembered as a great political leader. I suppose they all do. And perhaps he will be remembered longer than many other politicians of his age or ours. But it will always be for the same thing. Jeremy, Jeremy, bang, bang, woof, woof."[210]

Thorpe was the son and grandson of Conservative MPs, but decided to align with the small and ailing Liberal Party. After reading Law at Oxford University he became one of the Liberals' brightest stars in the 1950s. He entered Parliament at the age of 30, rapidly made his mark, and was elected party leader in 1967. After an uncertain start during which the party lost ground, Thorpe capitalised on the growing unpopularity of the Conservative and Labour parties to lead the Liberals through a period of notable electoral success. This culminated in the general election of February 1974, when the party won 6 million votes. Under the first-past-the-post electoral system this gave them only 14 seats, but in a hung parliament, no party having an overall majority, Thorpe was in a strong position. He was offered a cabinet post by the Conservative prime minister, Edward Heath, if he would bring the Liberals into a coalition. His price for such a deal, reform of the electoral system, was rejected by Heath, who resigned in favour of a minority Labour government. The February 1974 election was the high-water mark of Thorpe's career. Thereafter his and his party's fortunes declined, particularly from late 1975 when rumours of his involvement in a plot to murder Norman Scott began to multiply. Thorpe resigned the leadership in May 1976, when his position became untenable. When the matter came to court three years later, Thorpe chose not to give evidence to avoid being cross-examined by counsel for the prosecution. This left many questions unanswered; despite his acquittal, Thorpe was discredited and did not return to public life. From the mid-1980s he was disabled by Parkinson's disease. During his long retirement he gradually recovered the affections of his party, and by the time of his death was honoured by a later generation of leaders, who drew attention to his record as an internationalist, a supporter of human rights, and an opponent of apartheid.

Thorpe's homosexual activities from time to time came to the attention of the authorities, and were investigated by the police;[117] information was added to his MI5 file, but in no case was action taken against him.[118] In 1971 he survived a party inquiry after a complaint against him by Norman Scott, a riding instructor and would-be model. Scott maintained that in the early 1960s he had been in a sexual relationship with Thorpe, who had subsequently mistreated him. The inquiry dismissed the allegations.[119][120] but the danger represented by Scott continued to preoccupy Thorpe who, according to his confidant David Holmes, felt "he would never be safe with that man around".[121] Scott (known then as Norman Josiffe) had first met Thorpe early in 1961 when the former was a 20-year-old groom working for one of Thorpe's wealthy friends. The initial meeting was brief, but nearly a year later Scott, by then in London and destitute, called at the House of Commons to ask the MP for help.[122] Thorpe later acknowledged that a friendship had developed, but denied any physical relationship;[123] Scott claimed that he had been seduced by Thorpe on the night following the Commons meeting.[124] Over the following years Thorpe made numerous attempts to help Scott find accommodation and work,[19] but Scott became increasingly resentful towards Thorpe, threatening him with exposure.[125] In 1965 Thorpe asked his parliamentary colleague Peter Bessell to help him resolve the problem. Bessell met Scott and warned him that his threats against Thorpe might be considered blackmail; he offered to help Scott obtain a new National Insurance card, the lack of which had been a long-running source of irritation.[126] This quietened matters for a while, but within a year Scott came calling again. With Thorpe's agreement, Bessell began paying Scott a "retainer" of £5 a week, supposedly as compensation for the welfare benefits that Scott had been unable to obtain because of his missing card.[127] Bessell later stated that by 1968 Thorpe was considering ways in which Scott might be permanently silenced; he thought David Holmes might organise this.[128] Holmes had been best man at Thorpe's wedding, and was completely loyal to him.[129] When Scott unexpectedly married in 1968, it appeared that the problem might be over,[128] but by 1970 the marriage had ended.[129] Early in 1971 Scott moved to the village of Talybont, in North Wales, where he befriended a widow, Gwen Parry-Jones, to whom he recounted his tale of ill-treatment at the hands of Thorpe. She passed the information to Emlyn Hooson, who was MP for the adjoining Welsh constituency; Hooson precipitated the party inquiry which cleared Thorpe.[130] After Parry-Jones's death the following year, Scott fell into a depression and for a while was quiescent.[131] In time, he began to tell his story to anyone who would listen.[132] By 1974 Thorpe, at the crest of the Liberal revival, was terrified of exposure that might lose him the Liberal leadership. As Dominic Sandbrook observes in his history of the times: "The stakes had never been higher; silencing Scott had never been more urgent".[120]

Over the years Scott made several attempts to publicise his story, but no newspapers were interested. The satirical magazine Private Eye decided in late 1972 that the story "was defamatory, unproveable, and above all was ten years old".[133] From late 1974 Holmes took the lead in furthering plans to silence Scott; through various intermediaries he found Andrew Newton, an airline pilot, who said he would dispose of Scott for a fee of between £5,000 and £10,000.[134][135] Meanwhile, Thorpe procured £20,000 from Sir Jack Hayward, the Bahamas-based millionaire businessman who had previously donated to the Liberal Party, stating that this was to cover election expenses incurred during 1974. Thorpe arranged for these funds to be secretly channelled to Holmes rather than the party.[136] He later denied that this money had been used to pay Newton, or anyone else, as part of a conspiracy.[137][n 11] In October 1975, Newton made a bungled attempt to shoot Scott that resulted in the killing of Scott's Great Dane. Newton was arrested on charges of possession of a firearm with intent to endanger life, yet the press remained muted, possibly awaiting the bigger story that they hoped would break.[135] Their reticence ended in January 1976 when Scott, in court on a minor social security fraud charge, claimed he was being hounded because of his previous sexual relationship with Thorpe. This statement, made in court and thus protected from the libel laws, was widely reported.[139] On 29 January the Department of Trade published its report into the collapse of London & County Securities. The report criticised Thorpe's failure to investigate the true nature of the company before involving himself, "a cautionary tale for any leading politician".[140] Thorpe received some relief when his former colleague Peter Bessell, who had resigned from parliament and relocated to California to escape from a string of business failures, re-emerged in early February after discovery by the Daily Mail. Bessell gave muddled accounts of his involvement with Scott, but insisted that his former chief was innocent of any wrongdoing.[141] On 16 March 1976 Newton's trial began at Exeter Crown Court, where Scott repeated his allegations against Thorpe despite the efforts of the prosecution's lawyers to silence him. Newton was found guilty and sentenced to two years' imprisonment, but did not incriminate Thorpe.[142] The erosion of public support for the Liberal Party continued with several poor by-election results in March,[143] which the former leader Grimond attributed to increasing lack of confidence in Thorpe.[144] On 14 March, The Sunday Times printed Thorpe's answer to Scott's various allegations, under the heading "The Lies of Norman Scott".[145] Nevertheless, many of the party's senior figures now felt that Thorpe should resign.[143][146] Thorpe's problems multiplied when Bessell, alarmed by his own position, confessed to the Daily Mail on 6 May that in his earlier statements he had lied to protect his former leader.[147] Scott was threatening to publish personal letters from Thorpe who, to forestall him, arranged for The Sunday Times to print two letters from 1961. Although these did not conclusively indicate wrongdoing, their tone indicated that Thorpe had not been frank about the true nature of his friendship with Scott.[148] On 10 May 1976, amid rising criticism, Thorpe resigned the party leadership, "convinced that a fixed determination to destroy the Leader could itself result in the destruction of the Party".[149]

Although the press was generally quiet following Thorpe's resignation, reporters were still investigating him. The most persistent of these were Barry Penrose and Roger Courtiour, collectively known as "Pencourt", who had begun by believing that Thorpe was a target of South African intelligence agencies,[157] until their investigations led them to Bessell in California. Bessell, no longer covering for Thorpe, gave the reporters his version of the conspiracy to murder Scott, and Thorpe's role in it.[158] Pencourt's progress was covered in Private Eye, to Thorpe's extreme vexation; when the pair attempted to question him outside his Devon home early in 1977, he threatened them with prosecution.[159] Thorpe's relatively peaceful interlude ended in October 1977 when Newton, released from prison, sold his story to the London Evening News. Newton's claim that he had been paid "by a leading Liberal" to kill Scott caused a sensation, and led to a prolonged police investigation.[160] Throughout this period Thorpe endeavoured to continue his public life, in and out of parliament.[161] In the House of Commons on 1 August 1978, when it appeared certain he would face criminal charges, he asked the Attorney-General what sum of capital possessed by an applicant would prevent him from receiving legal aid.[162] The next day he made his final speech in the House, during a debate on Rhodesia.[163] On 4 August, Thorpe, along with Holmes and two of Holmes's associates, was charged with conspiracy to murder Scott. Thorpe was additionally charged with incitement to murder, on the basis of his alleged 1968 discussions with Bessell and Holmes. After being released on bail, Thorpe declared his innocence and his determination to refute the charges.[164][165] Although he remained North Devon's MP he withdrew almost completely from public view, except for a brief theatrical appearance at the Liberals' 1978 annual assembly on 14 September—to the annoyance of the party's leaders who had asked him to stay away.[166][167]

In November 1978, Thorpe, Holmes and two of the latter's business acquaintances, John le Mesurier (a carpet salesman, not to be confused with the actor of that name) and George Deakin, appeared before magistrates at Minehead, Somerset, in a committal hearing to determine whether they should stand trial. The court heard evidence of a conspiracy from Scott, Newton and Bessell;[168] it also learned that Bessell was being paid £50,000 by The Sunday Telegraph for his story.[169] At the conclusion, the four defendants were committed for trial at the Old Bailey.[170] This was set to begin on 30 April 1979, but when in March the government fell, and a general election was called for 3 May, the trial was postponed until 8 May.[171] Thorpe accepted the invitation of his local party to fight the North Devon seat, against the advice of friends who were certain he would lose. His campaign was largely ignored by the national party; of its leading figures only John Pardoe, the MP for North Cornwall, visited the constituency. Thorpe, supported by his wife, his mother and some loyal friends, fought hard, although much of his characteristic vigour was missing. He lost to his Conservative opponent by 8,500 votes.[172] Overall, the Conservatives obtained a majority of 43 seats, and Margaret Thatcher became prime minister. The Liberal Party's share of the national vote fell to 13.8%, and its total seats from 13 to 11. Dutton attributes much of the fall in the Liberal vote to the lengthy adverse publicity generated by the Thorpe affair.[173]

The trial, which lasted for six weeks, began on 8 May 1979, before Mr Justice Cantley.[174] Thorpe was defended by George Carman.[175] Carman quickly undermined Bessell's credibility by revealing that he had a significant interest in Thorpe's conviction; in the event of an acquittal, Bessell would receive only half of his newspaper fee.[176] During his cross-examination of Scott on 22 May, Carman asked: "You knew Thorpe to be a man of homosexual tendencies in 1961?"[177] This oblique admission of his client's sexuality was a stratagem to prevent the prosecution from calling witnesses who would testify to Thorpe's sex life.[178] Nevertheless, Carman insisted, there was no reliable evidence of any physical sexual relationship between Thorpe and Scott, whom Carman dismissed as "this inveterate liar, social climber and scrounger".[179] Following weeks in which the court heard the prosecution's evidence from the committal hearings, the defence opened on 7 June. Deakin testified that although he introduced Newton to Holmes, he had thought that this was to help deal with a blackmailer—he knew nothing of a conspiracy to kill.[180] Deakin was the only defendant to testify; Thorpe and the others chose to remain silent and call no witnesses, on the basis that the testimonies of Bessell, Scott and Newton had failed to make the prosecution's case.[181] On 18 June, following closing speeches from prosecution and defence counsel, the judge began his summing-up. While emphasising Thorpe's distinguished public record,[182] he was scathing about the principal prosecution witnesses: Bessell was a "humbug",[183] Scott a fraud, a sponger, a whiner, a parasite—"but of course he could still be telling the truth."[184] Newton was "determined to milk the case as hard as he can."[185] On 20 June the jury retired; they returned two days later and acquitted the four defendants on all charges. In a brief public statement, Thorpe said that he considered the verdict "a complete vindication."[186] Scott said he was "unsurprised" by the outcome, but was upset by the aspersions on his character made by the judge from the safety of the bench.[187]

In 1999 Thorpe published an anecdotal memoir, In My Own Time, an anthology of his experiences in public life. In the book he repeated his denial of any sexual relationship with Scott,[123] and maintained that the decision not to offer evidence was made to avoid prolonging the trial, since it was clear that the prosecution's case was "shot through with lies, inaccuracies and admissions".[201] In the 2005 general election campaign Thorpe appeared on television, attacking both the Conservative and Labour parties for supporting the Iraq War.[202] Three years later, in 2008, he gave interviews to The Guardian and to the Journal of Liberal History. York Membery, the Liberal journal's interviewer, found Thorpe able to communicate only in a barely audible whisper, but with his brain power unimpaired.[82] Thorpe asserted that he "still had steam in my pipes"; reviewing the current political situation, he considered the Labour prime minister Gordon Brown "dour and unimpressive", and dubbed the Conservative leader David Cameron "a phoney ... a Thatcherite trying to appear progressive".[200] Some of Thorpe's pro-Europeanism had been eroded over the years; In his final years, he thought that the European Union had become too powerful, and insufficiently accountable.[82]

Thorpe's last public appearance was in 2009, at the unveiling of a bust of himself in the Grimond Room at the House of Commons.[203] Thereafter he was confined to his home, nursed by Marion Stein, his second wife, until she became too infirm.[204] She died on 6 March 2014; Thorpe survived for nine more months, dying from complications of Parkinson's disease on 4 December, aged 85. His funeral was at St Margaret's, Westminster, on 17 December.[205]

In 2009, the BBC attempted to film a TV biopic of Thorpe's life, with Rupert Everett in the title role, but this was subsequently abandoned after legal threats from Thorpe.[217] A Very English Scandal, a true crime non-fiction novel covering the Thorpe/Scott affair, by John Preston, was published on 5 May 2016 by Viking Press.[218] The book was described as "a political thriller, with urgent dialogue, well-staged scenes, escalating tension and plenty of cliffhangers, especially once the trial begins".[219] A British three-part television series, also titled A Very English Scandal, based on Preston's novel, aired on the BBC in May 2018, directed by Stephen Frears, with actor Hugh Grant starring as Thorpe and Ben Whishaw as Norman Scott.[220]

My published books: