Queer Places:

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 118-128 N Broad St, Philadelphia, PA 19102, Stati Uniti

Moore College of Art & Design, 1916 Race St, Philadelphia, PA 19103, Stati Uniti

Drexel University, 3141 Chestnut St, Philadelphia, PA 19104, Stati Uniti

1523 Chestnut St, Philadelphia, PA 19102

Red Rose Inn, 1308 Mt Pleasant Rd, Villanova, PA 19085

Cogslea, 617 St Georges Rd, Philadelphia, PA 19119, Stati Uniti

Cogshill, 601 St Georges Rd, Philadelphia, PA 19119

The Woodlands, 4000 Woodland Ave, Philadelphia, PA 19104, Stati Uniti

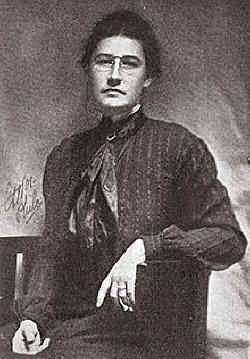

Jessie Willcox Smith (September 6, 1863 – May 3, 1935) was a prominent

female illustrator in the United States during the Golden Age of American

illustration[2]

and "one of the greatest pure illustrators".[3]

She was a prolific contributor to respected books and magazines during the

late 19th and early 20th centuries. Smith illustrated stories and articles for

clients such as Century, Collier's, Leslie's Weekly,

Harper's, McClure's, Scribners, and the Ladies' Home

Journal. She had an ongoing relationship with Good Housekeeping,

which included the long-running Mother Goose series of illustrations and also

the creation of all of the Good Housekeeping covers from December 1917

to 1933. Among the more than 60 books that Smith illustrated were

Louisa May

Alcott's Little Women and An Old-Fashioned Girl, Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow's Evangeline, and Robert Louis Stevenson's A

Child's Garden of Verses.

Jessie Willcox Smith (September 6, 1863 – May 3, 1935) was a prominent

female illustrator in the United States during the Golden Age of American

illustration[2]

and "one of the greatest pure illustrators".[3]

She was a prolific contributor to respected books and magazines during the

late 19th and early 20th centuries. Smith illustrated stories and articles for

clients such as Century, Collier's, Leslie's Weekly,

Harper's, McClure's, Scribners, and the Ladies' Home

Journal. She had an ongoing relationship with Good Housekeeping,

which included the long-running Mother Goose series of illustrations and also

the creation of all of the Good Housekeeping covers from December 1917

to 1933. Among the more than 60 books that Smith illustrated were

Louisa May

Alcott's Little Women and An Old-Fashioned Girl, Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow's Evangeline, and Robert Louis Stevenson's A

Child's Garden of Verses.

Jessie Willcox Smith was born in the Mount Airy neighborhood of

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She was the youngest girl born to Charles Henry

Smith, an investment broker, and Katherine DeWitt Willcox Smith.[4][5]

Jessie attended private elementary schools. At the age of sixteen she was sent

to Cincinnati, Ohio to live with her cousins and finish her education. She

trained to be a teacher and taught kindergarten in 1883. However, Smith found

that the physical demands of working with children were too strenuous for her.[4][6]

Due to back problems, she had difficulty bending down to their level.[5]

Persuaded to attend one of her friend's[7]

or cousin's art classes, Smith realized she had a talent for drawing.[5][8]

In 1884[8][9]

or 1885,[5]

Smith attended the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College

of Art and Design)[8]

and in 1885 attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in

Philadelphia under Thomas

Eakins' and Thomas Anshutz' supervision.[5][9][10]

It was under Eakins that Smith began to use photography as a resource in her

illustrations. Although Eakins' demeanor could be difficult, particularly with

female students, he became one of her first major influences.[10]

In May 1888, while Smith was still at the Pennsylvania Academy, her

illustration Three Little Maidens All in a Row was published in the

St. Nicholas Magazine. Illustration was one artistic avenue in which women

could make a living at the time.[5]

At this time, creating illustrations for children's books or of family life

was considered an appropriate career for woman artists because it drew upon

maternal instincts. Alternatively, fine art that included life drawing was not

considered "ladylike."[11]

Illustration partly became viable due to both the improved color printing

processes and the resurgence in England of book design.[12]

Smith graduated from PAFA in June 1888.[7]

The same year, she was hired for an entry-level position in the advertising

department of the first magazine for women, the Ladies' Home Journal.

Smith's responsibilities were finishing rough sketches, designing borders, and

preparing advertising art for the magazine.[6][13]

In this role, she illustrated the book of poetry New and True: rhymes and

rhythms and histories droll for boys and girls from pole to pole (1892) by

Mary Wiley Staver.[7]

During her time at the Ladies' Home Journal, Smith enrolled in 1894

in Saturday classes taught by Howard Pyle at Drexel University.[5][14]

She was in his first class, which was almost 50% female.[13]

Pyle pushed many artists of Smith's generation to fight for their right to

illustrate for the major publishing houses. He worked especially closely with

many artists whom he saw as "gifted". Smith would write a speech stating that

working with Pyle swept away "all the cobwebs and confusions that so beset the

path of the art-student."[15]

The speech was later compiled in the 1923 work "Report of the Private View of

Exhibition of the Works of Howard Pyle at the Art Alliance".[16]

She studied with Pyle through 1897.[17]

While studying at Drexel, Smith met

Elizabeth Shippen Green and

Violet Oakley, who

had similar talent and with whom she had mutual interests. They would develop

a lifelong friendship. The women shared a studio on Philadelphia's Chestnut

Street.[5]

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's Evangeline, illustrated by Oakley and

Smith, was published in 1897.[5]

At the turn of the twentieth century, Smith's career flourished. She

illustrated a number of books, magazines, and created an advertisement for

Ivory soap. Her works were published in Scribner's, Harper's Bazaar,

Harper's Weekly, and St. Nicholas Magazine. She won an award for

Child Washing.[18]

Green, Smith, and Oakley became known as "The Red Rose Girls" after the Red

Rose Inn in Villanova, Pennsylvania where they lived and worked together for

four years beginning in the early 1900s.[6][13]

They leased the inn where they were joined by Oakley's mother, Green's

parents, and Henrietta Cozens, who managed the gardens and inn.[5]

Alice Carter created a book about the women entitled The Red Rose Girls: An

Uncommon Story of Art and Love[19]

for an exhibition of their work at the Norman Rockwell Museum. Museum Director

Laurie Norton Moffatt said of them, "These women were considered the most

influential artists of American domestic life at the turn of the twentieth

century. Celebrated in their day, their poetic, idealized images still prevail

as archetypes of motherhood and childhood a century later."[11]

Green and Smith illustrated the calendar, The Child in 1903.[5]

Smith exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts that year and won the

Mary Smith Prize.[5][20]

When the artists lost the lease on the Red Rose Inn in 1904,[5][21]

a farmhouse was remodeled for them in West Mount Airy, Philadelphia by Frank

Miles Day.[22]

They named their new shared home and workplace "Cogslea", drawn from the

initials of their surnames and that of Smith's roommate, Henrietta Cozens.[5][21]

Cogshill, 601 St Georges Rd, Philadelphia, PA 19119

Though never a travel enthusiast, Smith finally agreed to tour Europe in

1933 with Isabel Crowder, who was both

Henrietta Cozens' niece and also a nurse.[48]

During her trip, her health deteriorated.[5]

Smith subsequently died in her sleep at her house at Cogshill in 1935 at the

age of 71.[49]

In 1936, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts held a memorial

retrospective exhibition of her works.[50]

In 1991, Smith became only the second woman to be inducted into The Hall of

Fame of the Society of Illustrators. Lorraine Fox (1979) had been the first

woman inductee. Of the small group of women inducted, three have been members

of The Red Rose Girls: Jessie Willcox Smith, Elizabeth Shippen Green (1994)

and Violet Oakley (1996).[11][51]

Smith bequeathed 14 original works to the Library of Congress' "Cabinet of

American Illustration" collection to document the Golden age of illustration

(1880-1920s).[52][53]

Smith's papers are on deposit in the collection of the Archives of American

Art at the Smithsonian Institution.[54]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jessie_Willcox_Smith#References

Jessie Willcox Smith (September 6, 1863 – May 3, 1935) was a prominent

female illustrator in the United States during the Golden Age of American

illustration[2]

and "one of the greatest pure illustrators".[3]

She was a prolific contributor to respected books and magazines during the

late 19th and early 20th centuries. Smith illustrated stories and articles for

clients such as Century, Collier's, Leslie's Weekly,

Harper's, McClure's, Scribners, and the Ladies' Home

Journal. She had an ongoing relationship with Good Housekeeping,

which included the long-running Mother Goose series of illustrations and also

the creation of all of the Good Housekeeping covers from December 1917

to 1933. Among the more than 60 books that Smith illustrated were

Louisa May

Alcott's Little Women and An Old-Fashioned Girl, Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow's Evangeline, and Robert Louis Stevenson's A

Child's Garden of Verses.

Jessie Willcox Smith (September 6, 1863 – May 3, 1935) was a prominent

female illustrator in the United States during the Golden Age of American

illustration[2]

and "one of the greatest pure illustrators".[3]

She was a prolific contributor to respected books and magazines during the

late 19th and early 20th centuries. Smith illustrated stories and articles for

clients such as Century, Collier's, Leslie's Weekly,

Harper's, McClure's, Scribners, and the Ladies' Home

Journal. She had an ongoing relationship with Good Housekeeping,

which included the long-running Mother Goose series of illustrations and also

the creation of all of the Good Housekeeping covers from December 1917

to 1933. Among the more than 60 books that Smith illustrated were

Louisa May

Alcott's Little Women and An Old-Fashioned Girl, Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow's Evangeline, and Robert Louis Stevenson's A

Child's Garden of Verses.