Partner Kenneth Halliwell

Queer Places:

Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, 62-64 Gower St, Bloomsbury, London WC1E 6ED, UK

31 Gower St, Fitzrovia, London WC1E 6HG, UK

25 Noel Rd, London N1 8HQ, UK

Golders Green Crematorium, 62 Hoop Ln, London NW11 7NL, UK

John

Kingsley "Joe" Orton (1 January 1933 – 9 August 1967) was an English

playwright and author. His public career was short but prolific, lasting from

1964 until his death three years later. During this brief period he shocked,

outraged, and amused audiences with his scandalous black comedies. The

adjective Ortonesque is sometimes used to refer to work characterised

by a similarly dark yet farcical cynicism.[1]

John

Kingsley "Joe" Orton (1 January 1933 – 9 August 1967) was an English

playwright and author. His public career was short but prolific, lasting from

1964 until his death three years later. During this brief period he shocked,

outraged, and amused audiences with his scandalous black comedies. The

adjective Ortonesque is sometimes used to refer to work characterised

by a similarly dark yet farcical cynicism.[1]

Orton was born at Causeway Lane Maternity Hospital, Leicester, to William A. Orton and Elsie M. Orton (nėe Bentley). William worked for Leicester County Borough Council as a gardener and Elsie worked in the local footwear industry until tuberculosis cost her a lung. When Joe was two years old, they moved from 261 Avenue Road Extension in Clarendon Park, Leicester, to 9 Fayrhurst Road on the Saffron Lane council estate.[2] He soon had a younger brother, Douglas, and two younger sisters, Marilyn and Leonie.

Orton attended Marriot Road Primary School, but failed the eleven-plus exam after extended bouts of asthma, and so took a secretarial course at Clark's College in Leicester from 1945 to 1947.[3] He then began working as a junior clerk on £3 a week.

Orton became interested in performing in the theatre around 1949 and joined a number of different dramatic societies, including the prestigious Leicester Dramatic Society. While working on amateur productions he was also determined to improve his appearance and physique, buying bodybuilding courses, taking elocution lessons, and trying to redress his lack of education and culture. He applied for a scholarship at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in November 1950. He was accepted, and left the East Midlands for London. His entrance into RADA was delayed until May 1951 by appendicitis.

Orton met Kenneth Halliwell at RADA in 1951 and moved into a West Hampstead flat with him and two other students in June of that year. Halliwell was seven years older than Orton and of independent means, having a substantial inheritance. They quickly formed a strong relationship and became lovers.

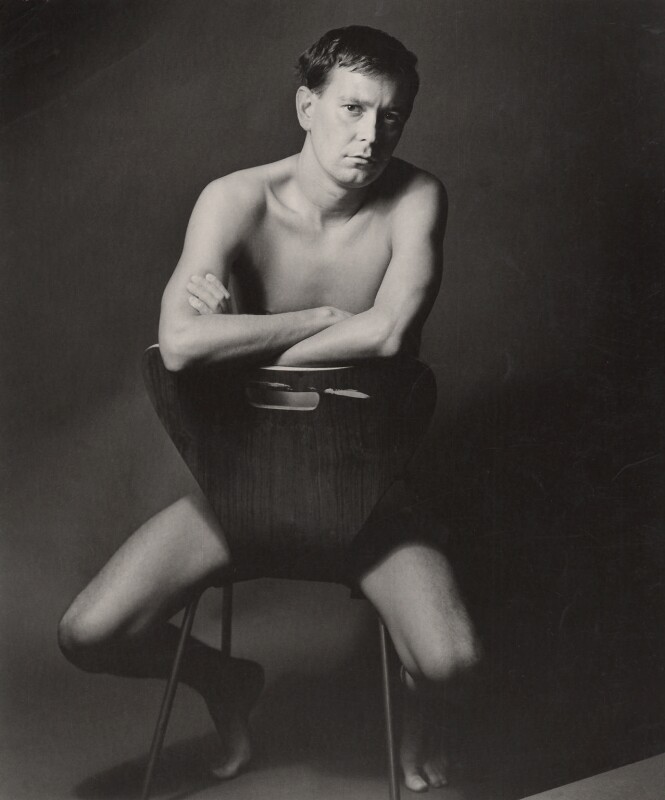

Joe Orton, by Lewis Morley, 1965

Joe Orton

by Lewis Morley

bromide print, 1965

20 in. x 16 1/8 in. (508 mm x 410 mm)

Given by the photographer, Lewis Morley, 1992

Primary Collection

NPG P512(16)

Joe Orton, by Patrick Procktor, 1967

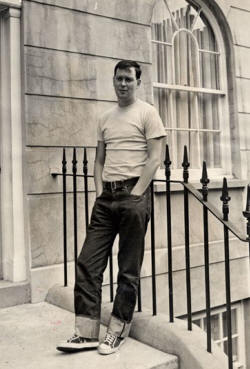

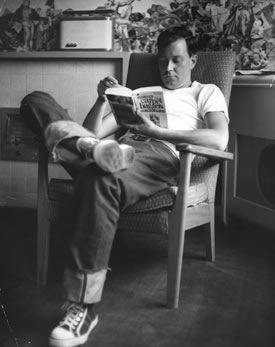

Joe in the flat at 25 Noel Rd in 1964, Courtesy The Leicester Mercury

joe-orton-in-islington-london-1967

interior-of-the-flat-at-25-noel-rd-showing-the-extent-of-the-collages

orton-halliwell-queens

orton-halliwell-secret

After graduating, both Orton and Halliwell went into regional repertory work: Orton spent four months in Ipswich as an assistant stage manager; Halliwell in Llandudno, Wales. Both returned to London and began to write together. They collaborated on a number of unpublished novels (often imitating Ronald Firbank) with no success at gaining publication. The rejection of their great hope, The Last Days of Sodom, in 1957 led them to solo works.[4] Orton wrote his last novel, The Vision of Gombold Proval (posthumously published as Head to Toe), in 1959. He would later draw on these manuscripts for ideas; many show glimpses of his stage-play style.

Confident of their "specialness", Orton and Halliwell refused to work for long periods. They subsisted on Halliwell's money (and unemployment benefits) and were forced to follow an ascetic life to restrict their outgoings to £5 a week. From 1957 to 1959, they worked in six-month stretches at Cadbury's to raise money for a new flat; they moved into a small, austere flat at 25 Noel Road in Islington in 1959.

A lack of serious work led them to amuse themselves with pranks and hoaxes. Orton created the alter ego Edna Welthorpe, an elderly theatre snob, whom he would later revive to stir controversy over his plays. Orton chose the name as an allusion to Terence Rattigan's "Aunt Edna", Rattigan's archetypal playgoer.

From January 1959, they began surreptitiously to remove books from several local public libraries and modify the cover art or the blurbs before returning them to the shelves. A volume of poems by John Betjeman, for example, was returned to the library with a new dustjacket featuring a photograph of a nearly naked, heavily tattooed, middle-aged man.[5] The couple decorated their flat with many of the prints. They were eventually discovered and prosecuted in May 1962. They were found guilty on five counts of theft and malicious damage, admitted damaging more than 70 books, and were sentenced to prison for six months (released September 1962) and fined £262. The incident was reported in the Daily Mirror as "Gorilla in the Roses".

Orton and Halliwell felt that that sentence was unduly harsh "because we were queers".[6] However, prison would be a crucial formative experience for Orton; the isolation from Halliwell would allow him to break free of him creatively; and he would clearly see what he considered the corruption, priggishness, and double standards of a purportedly liberal country. As Orton put it: "It affected my attitude towards society. Before I had been vaguely conscious of something rotten somewhere, prison crystallised this. The old whore society really lifted up her skirts and the stench was pretty foul.... Being in the nick brought detachment to my writing. I wasn't involved any more. And suddenly it worked."[7] The book covers that Orton and Halliwell vandalised have since become a valued part of the Islington Local History Centre collection. Some are exhibited in the Islington Museum.[8]

A collection of the book covers is available online.[9]

On 9 August 1967, Kenneth Halliwell bludgeoned 34-year-old Orton to death at their home in Islington, London, with nine hammer blows to the head, and then killed himself with an overdose of Nembutal.[25]

In 1970 The Sunday Times reported that four days before the murder, Orton had told a friend that he wanted to end his relationship with Halliwell, but did not know how to go about it.

Halliwell's doctor spoke to him by telephone three times on the day of the murder, and had arranged for him to see a psychiatrist the following morning. The last call was at 10 o'clock,[26] during which Halliwell told the doctor, "Don't worry, I'm feeling better now. I'll go and see the doctor tomorrow morning."

Halliwell had felt increasingly threatened and isolated by Orton's success, and had come to rely on antidepressants and barbiturates.[27] The bodies were discovered the following morning when a chauffeur arrived to take Orton to a meeting with director Richard Lester to discuss filming options on Up Against It. Halliwell left a suicide note: "If you read his diary, all will be explained. KH PS: Especially the latter part." This is presumed to be a reference to Orton's description of his promiscuity; the diary contains numerous incidents of cottaging in public lavatories and other casual sexual encounters, including with rent boys on holiday in North Africa. The diaries have since been published.[28]

Orton was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium, his maroon cloth-draped coffin being brought into the west chapel to a recording of The Beatles song "A Day in the Life".[26][29] Harold Pinter read the eulogy, concluding with "He was a bloody marvellous writer." According to Dennis Dewsnap's memoir, What's Sex Got To Do With It (The Syden Press, 2004), Orton and Halliwell had their ashes mixed and were buried together. Dewsnap writes about Orton's agent Peggy Ramsay: "...At the scattering of Joe's and Kenneth's ashes, his sister took a handful from both urns and said, 'A little bit of Joe, and a little bit of Kenneth. I think perhaps a little bit more of our Joe, and then some more of Kenneth.' At which Peggy snapped, 'Come on, dearie, it's only a gesture, not a recipe.'"[30] She described Orton's relatives as simply "the little people in Leicester",[31] leaving a cold, nondescript note and bouquet at the funeral on their behalf.

Orton's ashes lie in section 3-C of the Garden of Remembrance at Golders Green. There is no memorial.[32]

A pedestrian concourse in front of the Curve theatre in Leicester has been renamed "Orton Square".[33]

My published books: