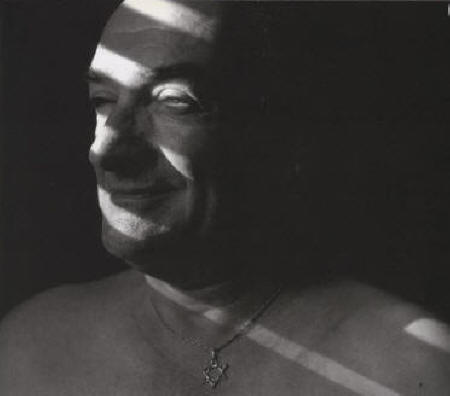

Joseph

Dittfeld (August 10, 1930 - December 18, 1999) was an Olocaust survivor. He

was featured in ''Family: a portrait of gay and lesbian America'', by Nancy

Andrews (1994).

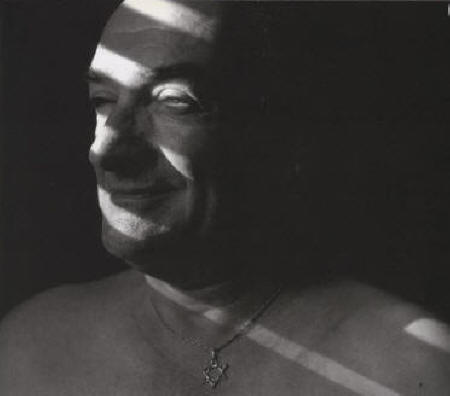

Joseph

Dittfeld (August 10, 1930 - December 18, 1999) was an Olocaust survivor. He

was featured in ''Family: a portrait of gay and lesbian America'', by Nancy

Andrews (1994).Queer Places:

1209 Decatur St, New Orleans, LA 70116

Joseph

Dittfeld (August 10, 1930 - December 18, 1999) was an Olocaust survivor. He

was featured in ''Family: a portrait of gay and lesbian America'', by Nancy

Andrews (1994).

Joseph

Dittfeld (August 10, 1930 - December 18, 1999) was an Olocaust survivor. He

was featured in ''Family: a portrait of gay and lesbian America'', by Nancy

Andrews (1994).

Joseph Dittfeld was born Joseph Gabler, a Jew, in 1930 in Germany. When he was eight years old he was picked up by the Nazis and placed in a concentration camp. Through bribery, his family bought false Italian citizenship papers that gave Joseph his freedom and a new name: Dittfeld. By the time he realized he was gay, Joseph had married, fathered a daughter, and divorced.

For ''Family: a portrait of gay and lesbian America'', he was photographed in his living room in New Orleans. Because of my experiences, I have never been afraid. The worst already happened to me. In late 1938, after Kristallnacht, I stayed with the nanny in Chemnitz, Germany. The early part of 1939, several months after I stayed with her, the Nazis found out who I was and picked me up and took me to a camp. I was eight. I knew what was happening. Eight-year-olds are not stupid. They picked me up with a lot of other people, put us on a truck, and took us to a train and took us to Leipzig, a collection camp. They numbered you, and collected you. They decided whether you should go to Auschwitz and be exterminated, or whether you should go to a labor camp as a slave. I just don't think about it. But it never leaves your mind. That picture is there. The first experience I had in the camp, a woman went into labor. She was just lying on the ground and two Nazis came over, and as the baby was coming out they grabbed it and pulled it out and took the baby and slammed it against the wall. Killed it. And the woman bled to death. I don't forget it. I mean you can't, but I don't think about it in my everyday life. After the whole thing was over, when I got off the boat in New York, the time was to make the decision to blot everything out and forget. Until recently, the last time I was in synagogue was when they burned it in Chemnitz, on Kristallnacht. The rabbi died in it. My grandfather, my aunt, my uncle—we stood there on the street across from the synagogue. The Germans were there cheering the Nazis on. I don't know what made me go back to the synagogue. It was probably a longing for tradition. Tradition means a Jewish way of life. There's a Jewish way of doing things: a Jewish way of cooking, a Jewish way of praying, a Jewish way of gathering. Tradition. You don't do it necessarily because you believe in God. I don't believe in God at all. Sometimes I envy people that have that belief. I go to synagogue because I am a Jew. I was born a Jew. I belong to these people. It's something I have to pass on to my children, my children's children. Just as the Jews are my people, the gays are my brothers and sisters. We, the Jews, wore the yellow star—the yellow star, which I wore, which my mother burned. They made the gays wear a pink triangle, which I didn't see. Now, gays have adopted this pink triangle. I disagree with that, to be used as it is, to walk around with the pink triangle on the lapel. A lot of people see the connection with the current persecution of gays and the extermination that the Nazis did. But it really doesn't fall into the same category. You take a group of people and you stick them in an oven—against being discriminated in housing. You can't just put the two together in the same category. You just can't do it. We have to put it in perspective. It is discrimination, period. And in this day and age, in this country, in this state, there shouldn't be any. Discrimination in any form is just not acceptable. "We are all created equal." That's the way it should be. Sadly enough, we are not.

My published books: