Joseph

F. Beam (December 30, 1954 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – December 27, 1988

in Philadelphia) was an African-American gay rights activist and author who

worked to foster greater acceptance of gay life in the black community by

relating the gay experience with the struggle for civil rights in the United

States.

Joseph

F. Beam (December 30, 1954 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – December 27, 1988

in Philadelphia) was an African-American gay rights activist and author who

worked to foster greater acceptance of gay life in the black community by

relating the gay experience with the struggle for civil rights in the United

States.His father Sun Beam worked as a bank security guard in Philadelphia. His mother, Dorothy, became a wage earner while still an adolescent, and attended evening classes to obtain her high school diploma. She later earned a college degree in elementary education and a master's degree from Temple University. She worked for more than twenty years as a teacher and guidance counselor in the Philadelphia school system.

Baptised a Catholic, the young Beam studied mainly in parochial schools, including the Malvern Preparatory School, St. Thomas More High School and Franklin College, a small liberal arts college founded by American Baptists in Franklin, Indiana (20 miles south of Indianapolis). An only child, his boyhood was difficult and solitary; he was often the only non-white pupil in his classes. Later, at Franklin College, he was influenced by the civil rights and the Black Power movements, and played an active role in the local Black Student Union. Also, as a member of the Franklin Independent Men, he helped organize several conferences on campus and was active in college journalism and radio programming. After graduation in 1976, Beam remained in the Midwest, enrolling first in a Master's Degree program in communications and then working as a waiter in Ames, Iowa. He returned to Philadelphia in 1979.

Giovanni's Room in the Center City District in Philadelphia was one of the main bookstores and contact points for lesbians and gays in the 1970s and 1980s. Beam, himself gay, became well acquainted with local and national gay figures and institutions while employed there in the early 1980s. His articles and short stories began appearing around the same time in numerous gay newspapers and magazines, including Au Courant, Blackheart, Changing Men, Gay Community News, Philadelphia Gay News, The Advocate, New York Native, Body Politic and the Windy City Times. The Lesbian and Gay Press Association awarded him a certificate for outstanding achievement by a minority journalist in 1984. The following year, he was hired as a consultant by the Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Friends Service Committee. He joined the Executive Committee of the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays in 1985, and became the editor of their new journal Black/Out.

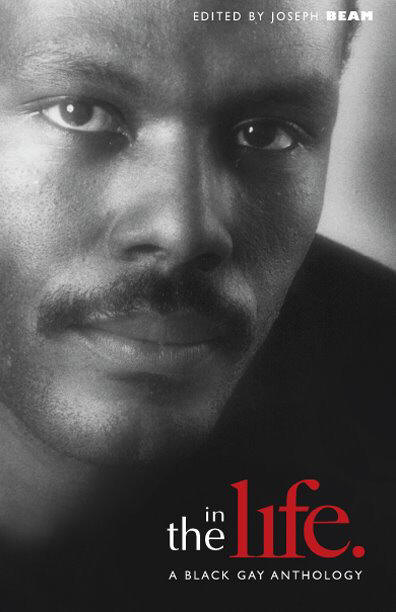

Beam began preparing and collecting materials for an anthology of writings by and about black gay men in 1982. His goal was to counteract the absence of positive images of gay men of color in the media and their exclusion from the cultural world of white gay rights activists. Inspired by the humanism of the black feminist and lesbian movement, he saw his work as part of a broad effort to correct and redefine the reality of race, sex, class and gender in the United States. Through his writings, he sought to alleviate the alienation of black homosexuals and help create a community of their own. In the Life was published by Allyson Press in 1986; it was the first anthology of writing by gay black men. It was ignored by most African-American critics and institutions, but was greeted as a literary and cultural milestone in the gay community.

Joseph F. Beam was working on a sequel to In the Life at the time of his death of HIV-related disease in 1988. This work was completed by Dorothy Beam and the gay poet Essex Hemphill, and published under the title Brother to Brother in 1991. Both books were featured in a television documentary, Tongues United, in 1991. “As a writer, Joe was more profound than prolific,” wrote his friend Craig Harris after his death. “His articles and essays were poetic, containing turned phrases and puns, metaphors in meters that made his writing musical with penetrating meaning. He took great pride in his skill and devoted time to multiple rewrites, crafting his work to create the style which other writers of the Black genre dubbed 'Beamesque'.”