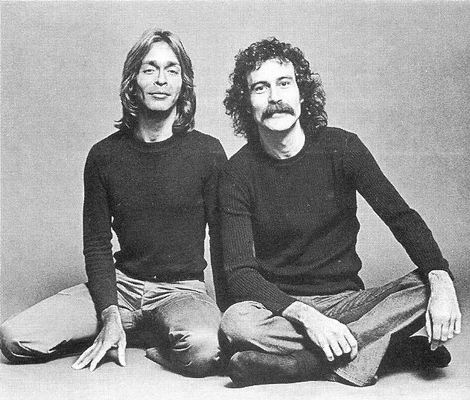

Partner Jack Nichols

Queer Places:

Cocoa, FL, USA

Elijah Hadyn "Lige" Clarke[1] (February 22, 1942 − February 10, 1975) was an American LGBT activist and journalist. Together with his partner Jack Nichols, Clarke created and wrote "The Homosexual Citizen" as a continuation to their original column written for The Mattachine Review beginning around 1965, however, the name "Homosexual Citizen" came from a newsletter originally written by Dr. Lilli Vincenz in the 1950s and then continued as the official newsletter of the Washington D.C. Mattachine Society. "The Homosexual Citizen", running in ''Screw'' magazine, was the first regular LGBT-interest column printed in a non-LGBT publication. As a result of the success of their column, Nichols and Clarke became known as the "most famous gay couple in America"—making them the first and only "Super-Stars" the gay community had ever known. In 1969, building on the success of the column, the two talked publisher Al Goldstein into publishing the first weekly national homosexual magazine called "Gay".

Elijah Hadyn "Lige" Clarke[1] (February 22, 1942 − February 10, 1975) was an American LGBT activist and journalist. Together with his partner Jack Nichols, Clarke created and wrote "The Homosexual Citizen" as a continuation to their original column written for The Mattachine Review beginning around 1965, however, the name "Homosexual Citizen" came from a newsletter originally written by Dr. Lilli Vincenz in the 1950s and then continued as the official newsletter of the Washington D.C. Mattachine Society. "The Homosexual Citizen", running in ''Screw'' magazine, was the first regular LGBT-interest column printed in a non-LGBT publication. As a result of the success of their column, Nichols and Clarke became known as the "most famous gay couple in America"—making them the first and only "Super-Stars" the gay community had ever known. In 1969, building on the success of the column, the two talked publisher Al Goldstein into publishing the first weekly national homosexual magazine called "Gay".

Born in 1942

in Cave Branch, a hollow

in

Knott

County

just outside

the town of Hindman, Lige Clarke had

deep roots in

eastern Kentucky as the grandson of lawyer-educator George Clarke on his

father’s

side and

store owner

Elijah Hicks on his mother’s. His father, James Bramlette Clarke (1912-1977) operated the

town's general store and chaired the county Republican Party. His uncle John

was the postmaster. His mother was

Corinne Hicks (1909–1965).

Clarke

spent his early

years dividing his time between

a little white

house on

Cave Branch

and a residence above his grandfather’s (Hicks’s) store at “the forks of

Troublesome Creek”. Clarke’s father was a

Merchant

Marine

in World

War Two who, upon returning

home when the boy

was seven,

built a large building

on the main

street of

Hindman,

where he operated

a general

store and

moved

the family

into a

downstairs apartment.

An aspiring actor

who

spent summers as a

teen at Bard’s Theatre in Abingdon,

Virginia,

Clarke thrived

at

Knott County

High School

(now the Kentucky

School

of Craft,

58 Education Lane,

Hindman).

He was also a religious youth who

was involved

with the Ivis Bible Church,

now Hindman First Methodist Church. Clarke graduated from

Eastern Kentucky

University and then

left

to join the U.S.

Army.

Clarke felt

loved and affirmed in

his home community,

where he had

been since childhood

and

remained

“everyone’s favorite.”

He returned frequently to

Hindman and /span>

often wrote

and spoke

affectionately of

it. His memories reflect

a

warmth and

an attachment to

the place and

people of

his upbringing,

but also an

ambivalence— in

part, perhaps, due to the economic decline he witnessed

in eastern

Kentucky

in those years,

which

fueled

his outrage at any injustice.

Four years before Stonewall, Lige Clarke—who worked at the Pentagon

in

the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff— became part of a small band of

Washington

D.C. Mattachine Society activists who staged the first openly gay picket in

front of

the White House on April 17, 1965—at a time when, as one of their peers put

it,

“picketing

was still

the

extreme expression of

dissent.”

Clarke allegedly

hand-lettered

nine

of the ten picket signs himself,

some of which

read “Gay is good!”—

which

in those mid-sixties years became a kind

of rallying cry

to combat the guilt

and shame heaped on gay people

by the larger society.

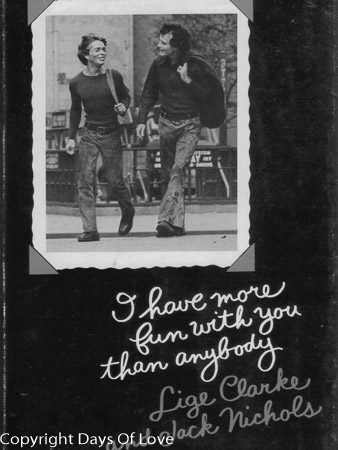

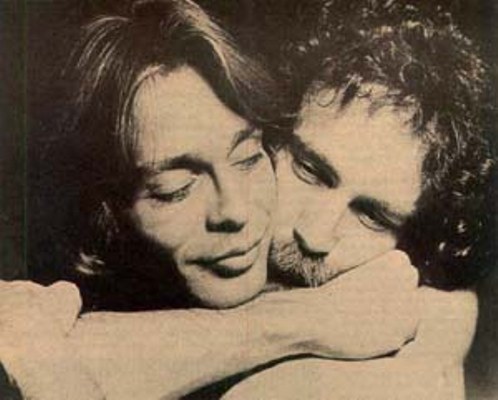

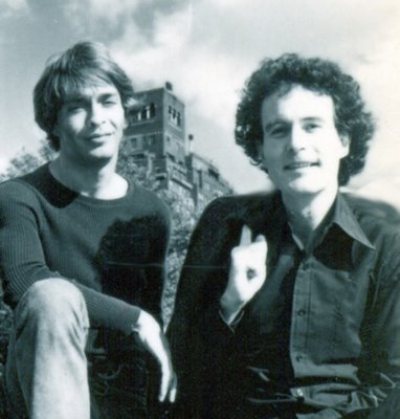

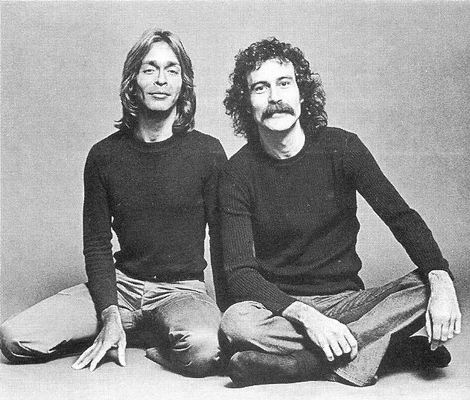

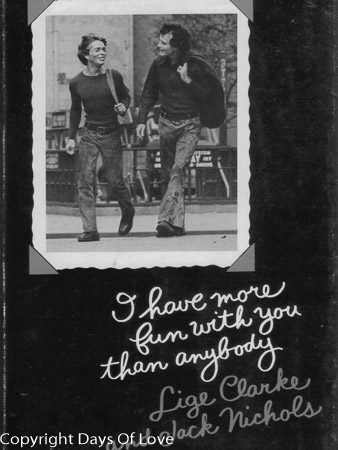

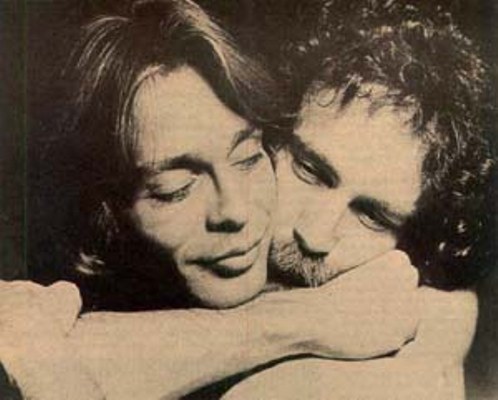

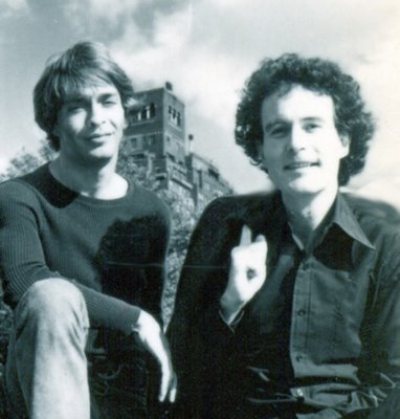

Lige and Jack by Eric Stephen Jacobs

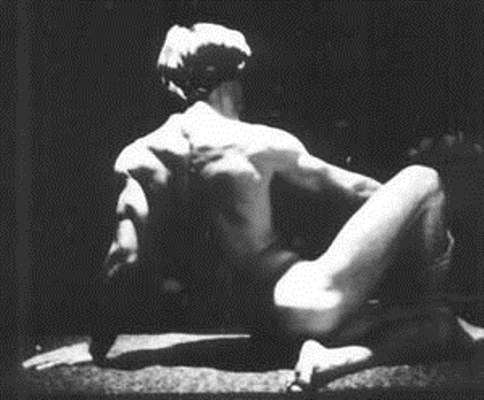

by by Roy Blakely

Lige Clarke in New York (2nd from L) with partner Jack Nichols (3rd from L) and other gay liberationists, circa 1970. Photos courtesy of Shelbiana Rhein.

Jack Nichols met Lige at the Hideaway in Washington, DC, in 1964. Jack spotted a

shapely army man wearing "a blue shirt that showed his absolute definition.

His face had classic simmetry, his cheekbones high, his jaw strong, his eyes

hazel with lips full. He was blonde, his hair styled in a civilian mode, a

handsome wave directly above his forehead. I'd never seen anyone like him. The

description penned by Old Walt in his Leaves came to mind: "Dress

does not hide him / The strong sweet quality he has strikes through."

Nichols and Clarke had a break in mid-1967, when an exasperated Lige walked

out on the "first and only man I've ever loved," due to Jack's deepening

political focus on "saving the world" instead of savoring the relationship

they shared. When they came back together, they moved to New York and lived in a East Village apartment, near Tompkins

Square Park. Jack worked for Countrywide Publications where he edited

magazines like Strange Unknown and Companion; Lige occasionally modeled and

wrote for Countrywide. They became friends of Al Goldstein, an editor who

dreamed of creating a magazine that capitalized on the sexual revolution. In

November 1968, Screw hit the newsstands. In June 1969 Nichols and Clarke moved

to Lower East Side across from Fillmore East. In 1969 they launched GAY. The

cover of the first issue featured Lige wearing a white fish-net tank and

standing near an ocean vessel.

Clarke did not fully come out

to most members of his family. The exception was his

sister,

Shelbiana,

to whom he was extremely

close, and who with her young son and

daughter had

visited

their “Uncle Lige”

and “Uncle Jack”

in their East Village

apartment.

And even with Shelbi,

Clarke waited

until the 1970s,

long after she had

inferred his sexual path, to make it

plain. Afterwards, he told

her that he would

not

be surprised if her twelve-year-old son Eric also turned

out to be

gay, and in fact,

Lige’s reputed

clairvoyance appeared

to be validated

in that case.

As a young adult,

Eric Rhein later became

among

the nation’s first visual artists to come out publicly

as being HIV-positive (in 1987). Although Eric Rhein

never lived

in Hindman,

he spent part of

most summers there throughout

his childhood

and claimed

his

Kentucky

background

proudly,

most especially

the mentorship

provided

by his

uncle.

On February 10, 1975, Clarke was shot and killed near Veracruz, Mexico while driving toward Veracruz with his traveling companion, Charlie Black. For some reason, Black was only wounded while Lige Clarke was shot through the chest multiple times. Black and Clarke were pursued by two motorcycles who, with two riders each--one to drive the bike and one with an automatic machine gun--and eventually the vehicle crashed into a wall that was just outside the town square of San Julian de Vera Cruz. A man had just died in the village and the priest and doctor were standing in the village square when the shooting took place. The priest yelled at the gunmen and scared them off.

Lige was traveling from Cocoa Beach, Florida to Veracruz, Mexico in one of his

many round-the-world adventures. He was traveling with a man named Charlie

Black who he and Jack Nichols had met who worked for the United States Post

Office in the Cocoa Beach Branch. Since Charlie owned a Ford Pinto and offered

to drive, that was all the impetus that Lige seemed to need.

When they crossed the border into Mexico, the Mexican customs held both Clarke and Black longer than what seemed reasonable and they seemed unusually obsessed with the rough-draft of the newest book he and Jack Nichols had been working on together, "Men's Liberation: A New Definition of Masculinity", along with the other books that he and Jack had already done ("I have more fun with you than anybody" and "Roommates Can't Always Be Lovers"). It's possible that the Mexican government thought that, after checking Lige Clarke's background and discovering that he formerly held one of the United States' highest security clearances as a military adjunct to the Secretary of Defense during his service in the army, that he had been sent to Mexico as an "agitator" under the guise of a gay rights activist.

His father

and siblings,

with the help of

Kentucky

U.S. Rep. Carl

Perkins

(also a Hindman native), had

Clarke’s

body flown

home to

Hindman,

and Jack Nichols joined

them there at the family’s church for the funeral,

where he was treated

as if he were a

family

member.

Lige Clarke is buried

in the

Hicks Family

Cemetery,

which

lies on a

shaded hillside overlooking

Highway 550

just east of the Hindman city

limits.

Late in his life, Jack Nichols pondered whether the men who killed his soul mate might have worked for the Mexican Federales and killed Lige because they suspected he worked for the CIA and in other ponderings, he wondered whether Charlie Black might have worked for either the CIA or for the FBI and had in some way been involved with Jack's father, who was with the FBI and who had, many years before, threatened his life because he was a gay rights activist. He never found out the truth about what happened to Lige and why and it troubled him in his declining days.

After Lige's funeral in March 1975, (around April), Jack got a visit from Charlie Black who explained the circumstances of the murder. The circumstances he described did not match what Charlie had written to Shelbianna Rhein (Lige's sister) during his recovery.

Almost a year after Lige's murder, Jack received a postcard from Charlie dated January 18, 1976 which read:

"Jack, I trapped a butterfly and held it in my hand. I was blinded to its beauty as its wings struggled to escape. A ray of sun caught my eye and set the captive free. As it flew away it sprinkled its secrets on me."

Jack wrote in his memoirs, "What is Charlie trying to say?" It's likely that Charlie was taking responsibility for the murder of Clarke, as Lige Clarke often referred to himself as a "butterfly," from the ancient wisdom of Chang Choi: "I once dreamt that I was butterfly only to awake and wonder if I was a man who became a butterfly or a butterfly who dreamt he was a man."

The card was postmarked "San Francisco" but no one has seen or heard from Charlie since.

Jack's friend, Stephanie Donald, in one of many discussions with Nichols prior to his death in 2005, discussed Lige's death and Charlie Black with Jack. Nichols had for years wished to seek out Black and try to interrogate him more fully about what happened that night but he was both anxious and hesitant to resolve the matter, but felt sure that what happened had something to do with his father and felt that Charlie had been sent to destroy his life. At other times, he was just as sure that the murder had been carried out by Mexican authorities simply because they had discovered that Lige was gay when they searched his belongings at the Brownsville, Texas-Matamoros, Mexico border crossing.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

-

https://www.nps.gov/articles/upload/Statewide_LGBTQHeritageofKentucky-508-compliant.pdf

Elijah Hadyn "Lige" Clarke[1] (February 22, 1942 − February 10, 1975) was an American LGBT activist and journalist. Together with his partner Jack Nichols, Clarke created and wrote "The Homosexual Citizen" as a continuation to their original column written for The Mattachine Review beginning around 1965, however, the name "Homosexual Citizen" came from a newsletter originally written by Dr. Lilli Vincenz in the 1950s and then continued as the official newsletter of the Washington D.C. Mattachine Society. "The Homosexual Citizen", running in ''Screw'' magazine, was the first regular LGBT-interest column printed in a non-LGBT publication. As a result of the success of their column, Nichols and Clarke became known as the "most famous gay couple in America"—making them the first and only "Super-Stars" the gay community had ever known. In 1969, building on the success of the column, the two talked publisher Al Goldstein into publishing the first weekly national homosexual magazine called "Gay".

Elijah Hadyn "Lige" Clarke[1] (February 22, 1942 − February 10, 1975) was an American LGBT activist and journalist. Together with his partner Jack Nichols, Clarke created and wrote "The Homosexual Citizen" as a continuation to their original column written for The Mattachine Review beginning around 1965, however, the name "Homosexual Citizen" came from a newsletter originally written by Dr. Lilli Vincenz in the 1950s and then continued as the official newsletter of the Washington D.C. Mattachine Society. "The Homosexual Citizen", running in ''Screw'' magazine, was the first regular LGBT-interest column printed in a non-LGBT publication. As a result of the success of their column, Nichols and Clarke became known as the "most famous gay couple in America"—making them the first and only "Super-Stars" the gay community had ever known. In 1969, building on the success of the column, the two talked publisher Al Goldstein into publishing the first weekly national homosexual magazine called "Gay".