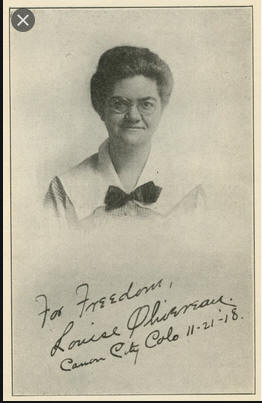

Louise

Olivereau (1884 - March 11, 1963) was a Seattle anarchist, poet and teacher;

Emma Goldman called her ”An

idealist of the finest type of American womanhood”; she worked at the Ferrer

Modern Day School in Portland, and for the I.W.W. in Seattle; she helped

organize Goldman’s lectures in Portland. She served two years in prison for

anti-conscription activism, and corresponded with Goldman in Jefferson City

Prison when Olivereau was in Canyon City, CO. She contributed to Mother

Earth Bulletin after Goldman was imprisoned and Mother Earth

closed down.

Louise

Olivereau (1884 - March 11, 1963) was a Seattle anarchist, poet and teacher;

Emma Goldman called her ”An

idealist of the finest type of American womanhood”; she worked at the Ferrer

Modern Day School in Portland, and for the I.W.W. in Seattle; she helped

organize Goldman’s lectures in Portland. She served two years in prison for

anti-conscription activism, and corresponded with Goldman in Jefferson City

Prison when Olivereau was in Canyon City, CO. She contributed to Mother

Earth Bulletin after Goldman was imprisoned and Mother Earth

closed down.

Louise Olivereau was the daughter of immigrants, with a French father,

a minister, and a German mother. She was born around 1884 in Wyoming and

educated as a stenographer at what later became Illinois State University.

She worked in resort camps as a cook. An anarchist and poet, she acted as

assistant to William Thurston Brown in setting up a Modern Schol in

Portland, run on the principles of Francisco Ferrer. In March 1915 she and

H.C. Uthoff set up the Portland Birth Control League, holding meetings and

distributing literature, following local agitation by Emma Goldman. She

moved to work as a stenographer in the offices of the Industrial Workers

of the World (IWW) in Seattle later in the year.

When the United

States went to War on the side of the Allies in 1917, Congress passed The

Espionage Act in June of that year, making it a crime to incite

insubordination in the armed forces, to obstruct the recruitment of

soldiers, and to use the mails to do so. The IWW took an anti-war

position, and already targeted by the authorities because of their

agitation among workers, now became seen as even more of a threat.

In August 1917, Olivereau spent $40 of her own money (she only earned

around $15 dollars a week) to mimeograph and post letters and circulars

encouraging young men to refuse the draft and become conscientious

objectors. On September 5, 1917, Bureau of Investigation agents, raided

the Seattle IWW and confiscated literature.

Two days later, Olivereau went to the agents' office to retrieve her

property. The agents attempted to get Olivereau to admit that the IWW was

behind the circulars, but she insisted that she acted alone. They went

with her to her home where they confiscated more documents and then

arrested her. She later said that she had told the agents that “if out of

2,000 circulars I could persuade five men to consider the connection

between the individual and government and war, I would consider myself

quite successful”.

Olivereau was indicted on three counts of

violation of The Espionage Act in connection with a letter and circular

posted to one man in Bellingham. At the trial, she defended herself,

saying that an attorney "would worry more over getting me a light sentence

than over the preservation of the ideals I care for more than for my own

liberty."

In court she readily admitted her actions, defended her

concept of Anarchism and described the American government as an apparatus

to protect the property of the rich. The jury convicted Olivereau and the

judge sentenced her to 10 years in prison on November 30th 1917. He

finished by declaring Miss Olivereau a woman above the average in

intelligence, and hoped she would change her ideas to conform to organized

government.

She served 28 months in the state penitentiary in Cañon

City, Colorado, before being paroled. The first year she was not allowed

to receive any letters, magazines or newspapers.The IWW provided no

support for Olivereau or her case because of her openly professed

allegiance to anarchism in court. Her case was hardly mentioned in IWW

newspapers and no other IWW member attended her trial. Only

Anna Louise Strong,

whom she knew from her visits to the IWW offices, appeared in court to

support her. As a result she lost her job with the Seattle School Board

and subsequently started working as a radical journalist.

Despite

this, Olivereau , once the ban on newspapers was lifted, always looked

forward to receiving IWW newspapers in jail. She ran classes in prison

teaching other prisoners English.

Released in March 1920, Olivereau

stayed with a friend in Portland, Oregon, where she spoke to union

meetings and women’s clubs, distributed pamphlets and supported herself

with secretarial work. She spoke to Finnish workers in Portland on May

Day. She planned on giving the proceeds of her meetings to support the

movement in Mexico inspired by the anarchist Ricardo Flores Magon. She got

a job as a stenographer but was disgusted that as an anarchist she had to

type out a book on accounting. When she told the boss that he should give

his workers a pay rise she was sacked. She then was contemplating,

according to the last letter she wrote to friends in the movement, looking

to work in a delicatessen or a café. These last few letters of hers reveal

her sadness at the way so many of her old friends would have nothing to do

with her because of her anti-war stance. She now disappeared into

obscurity, continuing to work at a variety of clerical and sales jobs in

Oregon and California. She settled in San Francisco in 1929 and worked as

a stenographer. She died there on March 11th 1963.

My published books: