Partner Ani Königsberger

Queer Places:

1632 L St, Lincoln, NE 68508

Wyuka Cemetery

Lincoln, Lancaster County, Nebraska, USA

Louise

Pound (June 30, 1872 – June 28, 1958) was an American folklorist, linguist,

and college professor at the University of Nebraska. In 1955, Pound was the

first woman elected president of the Modern Language Association, and in the

same year, she was the first woman inducted into the Nebraska Sports Hall of

Fame. Louise Pound had an intimate relationship with Ani Königsberger, daughter of

the mathematician and historian of science Leo Königsberger,[3][4] in

which letters were regularly exchanged for over half a century; Krohn notes

that "since the letters that Louise wrote to Ani aren't available, the essence

of their friendship remains a mystery",[5] but

observes that their correspondence was characteristic of intimate

relationships between women of the time, which were "of great emotional

strength and complexity... intimacy, love, and erotic passion", even if the

exact nature of their friendship, "ardent on Ani's part, almost an

infatuation", meant that "that passion was not always fulfilled".

Nevertheless, Ani was Pound's "closest companion" and "most intimate and

enduring friend".[6] They

began their relationship as classmates who both loved the game of tennis

leading to their intense and emotional companionship. Both Pound and

Königsberger shared similar interests such as athletics and the outdoors.[7] The

two would spend time together; Königsberger bringing Pound on hikes and climbs

while Pound teaching Königsberger "the net game" in tennis. Pound, focusing on

her professional life in teaching and scholarship, did not continue her

intimate relationship with Königsberger, who later married a physician, Max

Phister, who practised at Hong Kong before the Second World War and later

at Beidaihe on the coast in North China. Although both German, the couple were

strongly anti-Nazi.[7][8]

Louise

Pound (June 30, 1872 – June 28, 1958) was an American folklorist, linguist,

and college professor at the University of Nebraska. In 1955, Pound was the

first woman elected president of the Modern Language Association, and in the

same year, she was the first woman inducted into the Nebraska Sports Hall of

Fame. Louise Pound had an intimate relationship with Ani Königsberger, daughter of

the mathematician and historian of science Leo Königsberger,[3][4] in

which letters were regularly exchanged for over half a century; Krohn notes

that "since the letters that Louise wrote to Ani aren't available, the essence

of their friendship remains a mystery",[5] but

observes that their correspondence was characteristic of intimate

relationships between women of the time, which were "of great emotional

strength and complexity... intimacy, love, and erotic passion", even if the

exact nature of their friendship, "ardent on Ani's part, almost an

infatuation", meant that "that passion was not always fulfilled".

Nevertheless, Ani was Pound's "closest companion" and "most intimate and

enduring friend".[6] They

began their relationship as classmates who both loved the game of tennis

leading to their intense and emotional companionship. Both Pound and

Königsberger shared similar interests such as athletics and the outdoors.[7] The

two would spend time together; Königsberger bringing Pound on hikes and climbs

while Pound teaching Königsberger "the net game" in tennis. Pound, focusing on

her professional life in teaching and scholarship, did not continue her

intimate relationship with Königsberger, who later married a physician, Max

Phister, who practised at Hong Kong before the Second World War and later

at Beidaihe on the coast in North China. Although both German, the couple were

strongly anti-Nazi.[7][8]

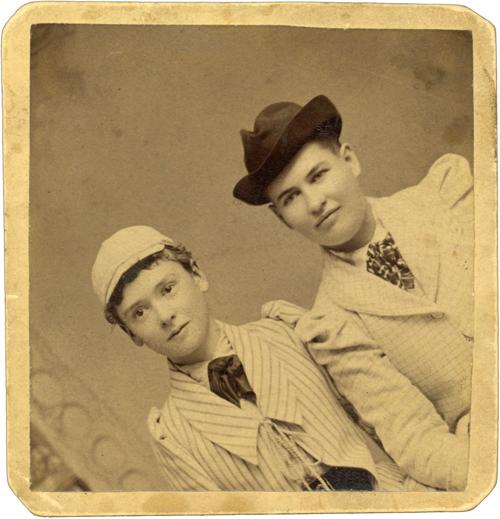

Louise Pound and Willa Cather, about 1890

Louise Pound as a preparatory school student.

Nebraska State Historical Society, rg0909 ph7 7

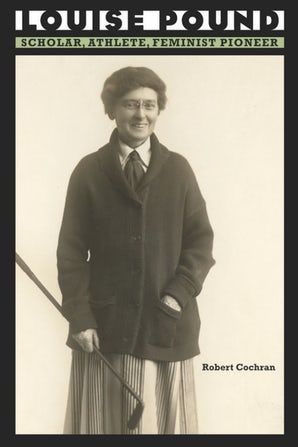

Studio portrait photograph of Louise Pound in profile, taken around 1902. Bernice Slote Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Pound was born in Lincoln, Nebraska to Stephen Bosworth Pound and Laura Biddlecombe, who had come to Lincoln in 1869. Alongside her older brother, noted legal professor Roscoe Pound, and her younger sister, Olivia Pound (who was to become a Lincoln High School administrator), Pound was instructed by her mother in various disciplines including the natural sciences, ancient and modern languages, and literature.[1] Pound studied at a preparatory school, the Latin School, in the School of Fine Arts, transitioning in 1888 to the University of Nebraska (B.B. 1892 and M.A., 1895).[1][2] Pound was an active student throughout the university. Along with her siblings and her colleague Willa Cather, she was a member of the University Union Literary Society at the University of Nebraska.[1] An orator for senior Class Day Exercises, Pound presented a speech entitled "The Apotheosis of the Common," an oration arguing the threat of prose to poetry, of the average to the individual. During her pursuit of a master's degree at the University of Nebraska, Pound began to teach at least one course in Anglo-Saxon in the English Department. In November 1892, Pound, Olivia, and Cather starred in two plays as part of the Union Branch of the University Drama club: one, a farce called The Fatal Pin; the other, Shakespeare Up to Date, a creative endeavor involving a plot of vengeance by Juliet (Pound), Ophelia (Olivia), and Macbeth (Cather).[1] A later production, A Perjured Padulion, was speculated to have been written by Louise Pound, as described by the Nebraskan and the Hesperian.[1] In January 1895, just before receiving her master's degree, Pound published a short story in the Nebraska State Journal, "By Homeopathic Treatment," describing an attempt at intervention for a socially conscious young woman, Matilda, by her friends, who attempt to introduce Matilda to Clementine, who believes woman's purpose is the selfless amelioration of society's evils. "By Homeopathic Treatment" was followed by "Miss Adelaide and Miss Amy" and "The Passenger from Metropolis," neither of which were published. Pound continued her studies at the University of Chicago and the University of Heidelberg, earning her PhD in philological studies in 1900. By then, she had authored "The Romaunt of the Rose: Additional Evidence that it is Chaucer's" (1896)—an essay on Chaucer's role in the English translation of Le roman de la rose—had read her paper "English Pronunciation in Shakespeare's Time" at a gathering of graduate students, and presented her paper "The Relation of the Finnsburg Fragment to the Finn Episode in Beowulf" at the fourth session of the Central Division of the Modern Language Association.[1] During her philological studies at the University of Chicago she also published "A List of Strong Verbs and Preterite Present Verbs in Anglo-Saxon" through the University of Chicago Press, an educational pamphlet meant to be used in her courses at the University of Nebraska. Pound completed her PhD at Heidelberg within a year, graduating magna cum laude.[1][2] Her dissertation, The Comparison of Adjectives in English in the XV and XVI Century, was supervised by Heidelberg's Professor Johannes Hoops. Shortly after attaining her PhD, Dr. Pound became an adjunct professor of English at the University of Nebraska—where she would stay for most of her career, becoming a full professor by 1912—under department chair Dr. Lucius Sherman, who had served as both her teacher and supervisor for her Master's.[1][2] Here her work would focus on American folklore and dialect studies.

Pound continued a correspondence with Ani Königsberger, her "most intimate and enduring friend", for fifty eight years.[24] Pound and Cather residence halls at the University of Nebraska (Lincoln) were named after Louise Pound and Willa Cather, with whom Pound maintained a close friendship. Some scholars argue that Louise Pound and Willa Cather's friendship verged on the romantic. Willa Cather biographers Phyllis C. Robinson and Sharon O'Brien argue that Pound was Cather's object of desire, O'Brien citing in her Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice (1987) Cather's 1892 and 1893 letters to Pound.[25][26] The 1892 letter expresses Cather's impression of Pound, Cather's feelings of strangeness around her, an anxiety of the "customary goodbye formality," and a noted disagreement with the perceived unnaturalness in "feminine friendships."[27] James Woodress, author of Willa Cather: A Literary Life (1987), argues that no evidence exists that Pound responded to Cather's affection.[28] Similarly, Marie Krohn, in Louise Pound: The 19th Century Iconoclast who Forever Changed America's views about Women, Academics and Sports (2008), notes that "Cather biographers always mention the Cather/ Pound relationship as an important chapter of Cather's life. Whether or not the friendship occupied an equally noteworthy place in Louise Pound's life is questionable", and observed that "as a woman who enjoyed freedom of movement and independence of thought, Louise would have felt emotionally suffocated by Cather's advances", which was a factor in the ending of their friendship by 1894.[29] Pound also maintained a distinct rivalry with Mabel Lee, a faculty member of the University of Nebraska physical education department.[1] Pound and Lee were initially cordial, yet differing perspectives on the role of athletics—Pound supported athletics as a field of competition, competition about which Lee maintained reservations—embittered their relationship.

Pound entered and won the Lincoln City Tennis Championship in 1890 and continued her tennis career competing against men for the University of Nebraska title in 1891 and 1892; winning both years.[30] At 18 years old, Louise competed and won the Women's Western Tennis Championship in 1897. Pound was not only the first and only female in school history to earn a men's varsity letter, she was also rated the top player in the country while working on her doctorate at Heidelberg University.[31] Very few times did Pound's tennis skills fall short. However, at the Ladies' Western Tennis Championship held in Chicago, Illinois, she was defeated playing a three-time U.S. Open singles champion, Juliette Atkinson.[7] Louise not only played tennis but also showed interest in golf, winning the state golf championship in 1916. Pound was an all-around athlete showing interest in figure skating, earning a 100-mile cycling medal in 1906, introducing skiing to Lincoln as well as being captain of her school's basketball team. She played center in their first women's basketball game in 1898 and continued to be involved with basketball by managing the university women's basketball team.[31] Pound is also the only woman in history to be inducted in the University of Nebraska Sports Hall of Fame, in 1955.[32] Pound continued her tennis journey by playing doubles with Carrie Neely, at the age of 43, and winning the 1915 Central Western and Western doubles championships. In 1926, at 54 years old, Pound won the Lincoln city championship, being the first women's state golf champion.[30]

Louise Pound died at a hospital in Lincoln on June 28, 1958, at the family home in Lincoln, after suffering from coronary thrombosis.[33] She was buried at Wyuka Cemetery.[34]

My published books: