Queer Places:

Friedhof Zollikerberg

Zollikon, Bezirk Meilen, Zürich, Switzerland

Lucia

Moholy, born Lucia Schulz, (18 January 1894, in Prague, Austria-Hungary — 17

May 1989, in Zürich, Switzerland) was a photographer and publications editor.

Her photos documented the architecture and products of the Bauhaus, and

introduced their ideas to a post-World War II audience. However Moholy was

seldom credited for her work, which was often attributed to her husband László

Moholy-Nagy or to Walter Gropius.[1][2]

Lucia

Moholy, born Lucia Schulz, (18 January 1894, in Prague, Austria-Hungary — 17

May 1989, in Zürich, Switzerland) was a photographer and publications editor.

Her photos documented the architecture and products of the Bauhaus, and

introduced their ideas to a post-World War II audience. However Moholy was

seldom credited for her work, which was often attributed to her husband László

Moholy-Nagy or to Walter Gropius.[1][2]

In the early 1910s Lucia Moholy studied philosophy, philology, and art

history at the University of Prague.[3]

In 1915 she shifted her attention to publishing, and worked as an editor for

several publishing houses in Germany.[3]

In 1919 she published radical, Expressionist literature under the pseudonym

"Ulrich Steffen".[3][4]

She met Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy in 1920 in Berlin, and married him

on her 27th birthday in January 1921. The two would spend five years at the

Bauhaus school, where Lucia Moholy would explore her affinity with

photography.[3][4]

Her husband became a master teacher at the Bauhaus in 1923, with Lucia

Moholy as his primary darkroom technician and an important collaborator.[4]

She also became an apprentice in Otto Eckner’s Bauhaus photography studio.

Moholy studied at the Leipzig Academy for Graphic and Book Arts (Hochschule

für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig), where she became a skilled photographer.[4]

Moholy documented the interior and exterior of Bauhaus architecture and its

facilities in Weimar and Dessau,[5][6]

as well as the students and teachers. Her aesthetic was part of the Neue

Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement, which focused on documentation from a

straightforward perspective. Moholy’s Bauhaus photographs helped construct the

identity of the school and create its image.[4]

Lucia Moholy and her husband experimented with different processes in the

darkroom, such as making photograms.[2][7][8]

In numerous publications, all of the experimentation the couple had done was

credited solely to "László Moholy-Nagy", such as the book Malerei,

Photografie, Film (1925; Painting, Photography, Film), which was

published only under her husband’s name.[4]

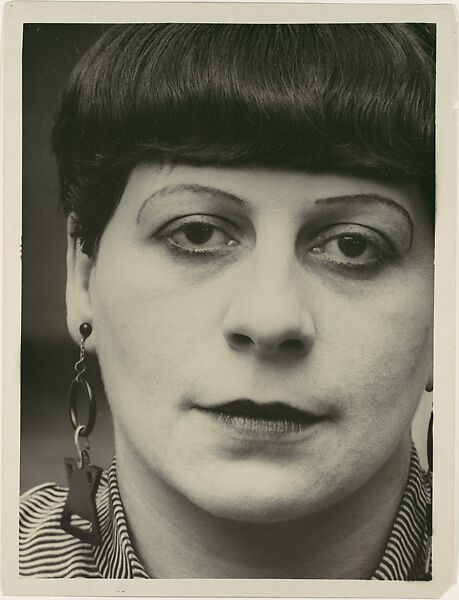

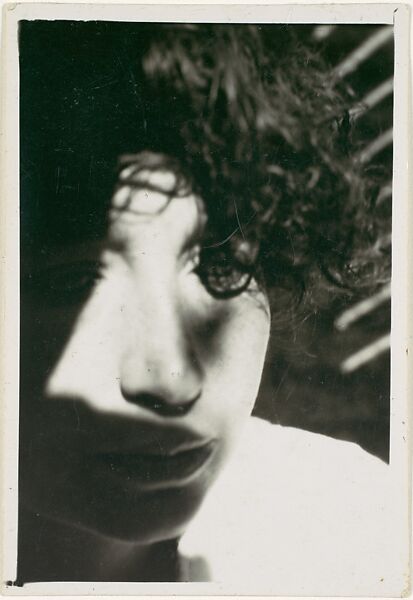

Florence Henri, 1927,

In her 1939 history of photography, Lucia Moholy cited Russian films as one source of inspiration for the new portraiture that emerged in the 1920s: "To the general public in Western Europe this style appears strange and exotic. They find it interesting and worth discussing, but few of them wish to have their portraits taken in the same way." In this formidable portrait of Florence Henri, a Paris-based painter who enrolled in Moholy-Nagy's summer course in 1927, Lucia Moholy employed the kind of extreme close-up that had recently thrilled Berlin audiences in Sergei Eisenstein's film Battleship Potemkin (1925).

Lucia Moholy

1920s

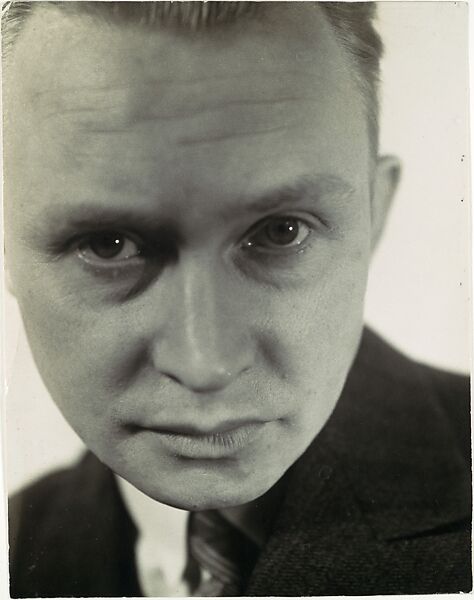

László Moholy-Nagy American, born Hungary

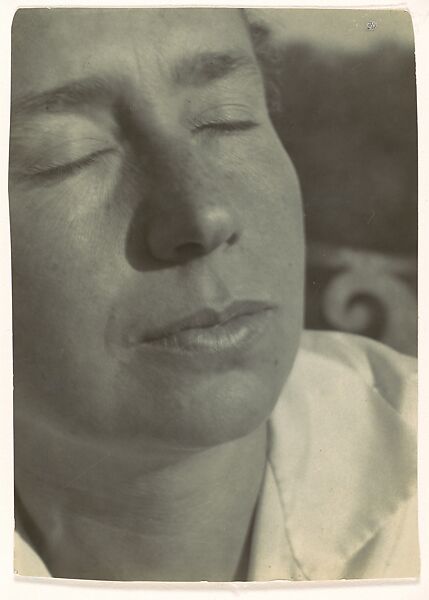

Franz Roh

1926

Lucia Moholy British, born Austria-Hungary

Roh was an art historian and a major apologist for the new vision. His trilingual book Foto-Auge (1929), published in the context of the Film und Foto exhibition, remains a most cogent summation of it. Lucia Moholy portrays him with eyes closed behind rimless glasses, as if to suggest the incompatibility of normal sight with insight. The portrait perfectly illustrated Andre Breton's 1925 statement: "...with closed eyes it is broad daylight to my silent contemplation."

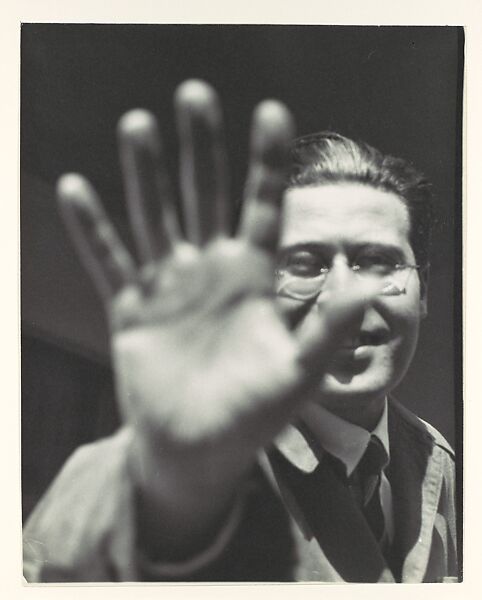

László Moholy-Nagy

1925–26

Lucia Moholy British, born Austria-Hungary

Lucia Moholy was one of the most prolific photographers at the Bauhaus between 1923 and 1928, while her husband, László Moholy-Nagy, was an instructor there. For both, photography was not simply a transparent window onto objective reality but a specific technology to be systematically explored in the modern spirit of exuberant experimentation. Here, illustrating the effect of selective focus, Moholy imprints his hand against the invisible picture plane that separates viewer and subject-a playful, disorienting gesture that collapses illusionistic depth into the concrete reality of the photographic image.

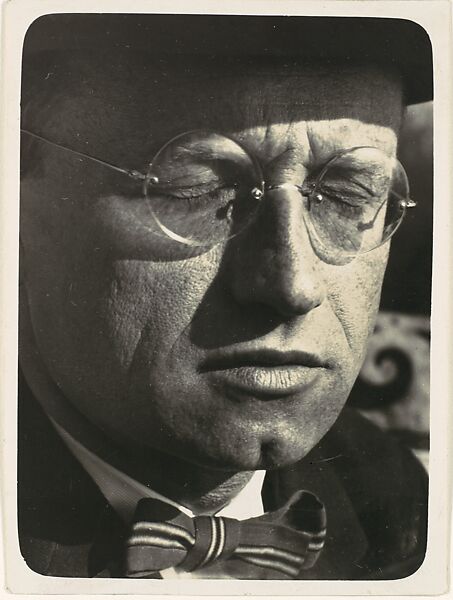

Georg Muche

1927

Lucia Moholy British, born Austria-Hungary

Lucia

1924–28

László Moholy-Nagy American, born Hungary

A professional photographer, Lucia Moholy taught her husband her craft and worked with him closely, developing and printing his pictures. She probably printed this photograph and was most certainly involved in the more complex process of creating a negative version of it, enabling a further exploration of the image's graphic and abstract qualities.

Margaret Goldsmith (Margaret Leland)

by Lucia Moholy

vintage bromide print, 1935

6 1/2 in. x 4 3/4 in. (164 mm x 120 mm) overall

Given by Bauhaus Archive, 1995

Photographs Collection

NPG x76390

In 1929 the couple separated. That same year Lucia Moholy was included in

the landmark exhibition in Stuttgart, Film and Foto. It featured artists working in the New Vision aesthetic

(Precisionism).[4]

Moholy then taught photography at a private art school in Berlin directed

by Johannes Itten. In 1933 when the Nazi Party rose to power, she emigrated to

London. There, she focused on commercial photography and teaching. She also

published a book, A Hundred Years of Photography, 1839-1939, written in English, which discussed in

depth the history of the medium.[1]

Moholy ran a microfilm operation based at the London Science Museum Library,

for the Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux (ASLIB),[9]

where she reduced the scale of photographic documents for storage at the

Library.[9]

She started a campaign to emigrate to the United States, but it never

succeeded, even though her ex-husband offered her a teaching position in

photography in Chicago around 1940.[2]

In 1946 to 1957, immediately after the World War II, she traveled to the

Near and Middle East for projects for UNESCO, where she did photographic

reproduction processes of graphic material and directed documentary films.[3]

Moholy moved in 1959 to Zollikon, Switzerland, where she wrote about her time

at the Bauhaus, and focused on art criticism.[4]

In 1972 she published Moholy-Nagy Notes[7]

which discussed the shared collaboration between herself and László

Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus, and attempted to reclaim artistic credit for her

photographs and experimentation.[4]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucia_Moholy

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265244

Lucia

Moholy, born Lucia Schulz, (18 January 1894, in Prague, Austria-Hungary — 17

May 1989, in Zürich, Switzerland) was a photographer and publications editor.

Her photos documented the architecture and products of the Bauhaus, and

introduced their ideas to a post-World War II audience. However Moholy was

seldom credited for her work, which was often attributed to her husband László

Moholy-Nagy or to Walter Gropius.[1][2]

Lucia

Moholy, born Lucia Schulz, (18 January 1894, in Prague, Austria-Hungary — 17

May 1989, in Zürich, Switzerland) was a photographer and publications editor.

Her photos documented the architecture and products of the Bauhaus, and

introduced their ideas to a post-World War II audience. However Moholy was

seldom credited for her work, which was often attributed to her husband László

Moholy-Nagy or to Walter Gropius.[1][2]