Queer Places:

Vassar College (Seven Sisters), 124 Raymond Ave, Poughkeepsie, NY 12604

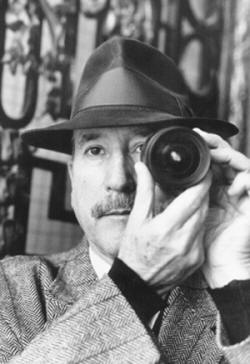

Néstor Almendros (October 30, 1930 - March 4, 1992) was an Academy Award-winning cinematographer.

He achieved his greatest renown working with

such directors as Eric Rohmer and François Truffaut, but he also directed several films himself, including

the blistering indictment of the persecution of homosexuals in Castro's Cuba, Improper Conduct (Mauvaise

conduite, 1984). In his autobiography,

Scotty Bowers claimed that Almendros bequeathed him his Oscar for his work

on Days of Heaven (1978). One of Manuel Puig's classmates was fellow gay

Nestor Almendros.

Néstor Almendros (October 30, 1930 - March 4, 1992) was an Academy Award-winning cinematographer.

He achieved his greatest renown working with

such directors as Eric Rohmer and François Truffaut, but he also directed several films himself, including

the blistering indictment of the persecution of homosexuals in Castro's Cuba, Improper Conduct (Mauvaise

conduite, 1984). In his autobiography,

Scotty Bowers claimed that Almendros bequeathed him his Oscar for his work

on Days of Heaven (1978). One of Manuel Puig's classmates was fellow gay

Nestor Almendros.

Almendros was born and grew up in Barcelona. Always an avid movie-goer, he joined a film society in 1946. The films that he saw there made him realize that movies could be an art form, not merely a source of entertainment. He later recalled his experience at the film society as his "entry into the world of cinema, my first moment of awareness." In 1948 he left Spain for Cuba, where his father had been living since going into exile after the Fascist victory in the Spanish Civil War in 1939. The young Almendros was delighted to discover the wide variety of international films shown in Cuba but disappointed by the absence of film societies and scholarly criticism. He therefore started the country's first film society. Among the other founding members were Guillermo Cabrera Infante, who went on to a career as a writer, and Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, who became a filmmaker. Almendros and several other members of the society aspired to a career in cinema but found the closed nature of the local media unions to be an obstacle. In any event, they hoped to make more serious films than the musicals and melodramas being produced in Cuba. In 1949 Almendros and Gutiérrez Alea made their first attempt at independent filmmaking with Una confusión cotidiana (A Daily Confusion), based on a story by Kafka. Almendros soon realized that he would need more training to succeed at his chosen profession. He enrolled in the Institute of Film Techniques at City College in New York. He was frustrated by the school's lack of resources, however, and in 1956 decided to pursue his studies at the Centro Sperimentale in Italy, but there he was disappointed by the quality of the instructors and their conservative views on cinematographic technique. Unwilling to return to the repressive political climate of either Batista's Cuba or Franco's Spain, Almendros went back to New York, where he got a job as a Spanish instructor at Vassar College. With the savings from his modest salary he bought a 16mm camera and began experimenting with the use and effect of light.

In 1959 Almendros returned to Cuba after the success of Castro's revolution. Although he eventually became bitterly disillusioned with Castro's policies, he initially embraced the hope that the new regime would bring positive changes. Almendros found a job with ICAIC, the Cuban government's department of cinematographic productions. He worked as a cameraman and as a director on propagandistic films with political or educational themes. Not satisfied with the nature of his official work, Almendros undertook an independent documentary project entitled Gente en la playa (People at the Beach). He experimented with the use of light, from the brilliant illumination of the sun at the beach to the relatively obscure interior of a crowded bus. Almendros was not reticent in expressing his ideas about film technique, which led to clashes with those in power at ICAIC. As a result, the materials for Gente en la playa were seized to prevent him from completing it. Eventually he was able to retrieve them, finish the editing, and sneak the film past the bureaucrats by retitling it Playa del pueblo (The Beach of the People). The film was later banned because it had been made without official sanctions. As a result of Castro's embrace of communism, the films being shown in Cuba came almost exclusively from the Soviet bloc. Moreover, Cuban film criticism was based on politics, rather than artistic merit. Almendros found this atmosphere stifling, and he again became an exile.

Almendros went to France, where he showed a smuggled copy of Gente en la playa at various film festivals. It was well received but did not lead to any offers of work. In 1964 Almendros was about to give up his dream of a career in cinema when he had a lucky break. He happened to be present when the director of photography on Eric Rohmer's Paris vu par... (Paris Seen By . . . ) quit. Almendros volunteered for the job. The producer, Barbet Schroeder, offered him a one-day trial, and then, pleased with his results, retained him. At that time Rohmer was working for French educational television. Knowing that Almendros needed work, he got him a job making educational documentaries. Between 1965 and 1967 Almendros made some two dozen such films. In 1966 Rohmer gave Almendros his first opportunity to be the director of photography on a feature film. La collectionneuse, which won a Silver Bear award at the Berlin Film Festival, brought Almendros to the attention of critics. He would go on to work on over fifty more films. Rohmer was the director of seven of these, including Ma nuit chez Maud (My Night at Maud's, 1969), Le genou de Claire (Claire's Knee, 1970), and Die Marquise von O. (The Marquise of O., 1975), which won the jury prize at the Cannes film festival in 1977. Almendros also had the opportunity to work on nine films with François Truffaut, whom he had long admired. Their first collaboration was on Domicile conjugal (Bed and Board, 1970). In the years to come, they would work together on such films as Histoire d'Adèle H. (The Story of Adèle H., 1975), L'homme qui aimait les femmes (The Man Who Loved Women, 1977), and Le dernier métro (The Last Métro, 1980), which was awarded the César prize for photography by the French Academy of Film Arts and Techniques. Almendros's work as a director of photography took him to Hollywood as well, where he was employed on a wide variety of projects, including Terence Malick's Days of Heaven (1976), which won him an Academy Award for best photography, Robert Benton's Kramer vs. Kramer (1978), Randal Kleiser's The Blue Lagoon (1979), Alan J. Pakula's Sophie's Choice (1982), and Robert Benton's Places in the Heart (1984). In his work as a cinematographer, Almendros was concerned above all with the question of light. Even in his earliest amateur film-making days, he studied and experimented with the use of natural available light. Critics have described him as painterly in his attention to light, color, and composition. This painterliness, combined with his willingness to take risks and attempt solutions to difficult lighting problems, made his work particularly attractive to nouvelle vague directors such as Rohmer and Truffaut, who sought verisimilitude rather than artificial effects in the appearance of their films. Rohmer praised Almendros for his precision and meticulousness, characteristics that are reflected in Almendros's discussion of his cinematographic work in his autobiography, A Man with a Camera (1984). With an artist's awareness, he explains what went into creating the ambiance needed for various scenes in his movies, always in the context of the director's vision of the story to be told. At the same time, he shows considerable technical expertise and ingenuity in meeting the challenges put to him.

In 1984 Almendros realized a project that combined several of his roots in filmmaking--directing, documentaries, and Cuba. Improper Conduct (Mauvaise conduite) uses filmed interviews with 28 Cuban exiles who had been interned in UMAP (Military Units to Aid Production) concentration camps. The former prisoners had been jailed for what the Castro regime considered dissidence, running afoul of the institutionalized homophobia of Cuban law. Almendros used this film as a vehicle to expose the persecution of gays, but he expressed the hope that viewers would understand that "this is only an aspect, perhaps the most absurd, of a greater repression." Critical reaction to the film was extremely positive. Improper Conduct was hailed as a powerful and important political documentary. It won several awards, including the Human Rights Grand Prix in Strasbourg. As an exposure of the Castro regime's brutal treatment of its homosexual citizens, Improper Conduct anticipates such works as Reinaldo Arenas's powerful account of his own persecution and imprisonment in Cuba, Before Night Falls (1993). In 1988 Almendros co-directed another documentary about repression in Cuba, Nobody Listened (Nadie escuchaba). Once again, the film drew its power from its directness--real people telling their horrifying stories in their own words. To Almendros, the words themselves and the expressive faces of the people uttering them were the most important elements of the film. He deliberately eschewed "arty lighting effects" and background music. An intensely private man, Almendros conducted his emotional and sexual life with great discretion. In his autobiography, he does not even mention his homosexuality. Almendros died at the age of 61 of AIDS-related lymphoma. He will be remembered as a master of using light to bring realism to films and of using films to bring harsh reality to light.

My published books: