Partner Dale Jennings, Bob Hull, Rodolfo Rentería

Queer Places:

756 Golden Gate Ave, San Francisco, CA 94102

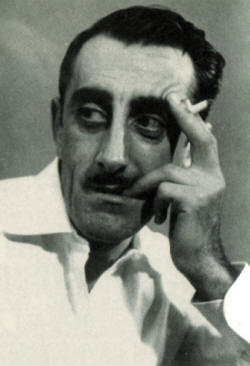

Paul Benard (April 24, 1916 – November 7, 1954) was one of the eight men, most of them early members of the Mattachine, pictured in the famous “Christmas tree” photograph taken by Jim Gruber in 1951. Benard turns out to have been considered for a role in the Mattachine’s leadership. He left the group and left Los Angeles but remained in contact with members, only to die in 1954.

Paul Benard (April 24, 1916 – November 7, 1954) was one of the eight men, most of them early members of the Mattachine, pictured in the famous “Christmas tree” photograph taken by Jim Gruber in 1951. Benard turns out to have been considered for a role in the Mattachine’s leadership. He left the group and left Los Angeles but remained in contact with members, only to die in 1954.

Benard was involved in the “little” and leftist theater endeavors of New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, and the members of the Mattachine saw him as a comrade. In early 1952 Mattachine cofounder Bob Hull took up with Paul Benard, an actor and writer who had become involved in the organization and was being considered for entry into the Fifth Order, the group’s top echelon.

Paul Charles Benard was born Charles Roy Coté Jr. on April 24, 1916 in Lowell, Massachusetts, to Lowell native Charles Roy Coté, a machinist, and mother Eleanor F. Smith, a native of Provincetown. His parents are listed in Lowell’s city directory for 1917 and 1918 but are absent in the directory thereafter. Charles Jr.’s mother died in Lowell in 1921, when he was about five years old. In 1930, a few days before his fourteenth birthday, he was living or staying in Lowell with his grandfather, also named Charles Coté, an ice company stableman, and grandmother Annie Baker. That June he graduated from Bartlett Junior High in Lowell, reciting in the ceremony “Our Flag”—“When you see the Stars and Stripes displayed, son, take off your hat. Some may titter”—attributed to Alvin M. Owsley, a past National Commander of the American Legion.

Mattachine Society cofounder Chuck Rowland remembered Paul Benard as “a radio/TV/movie/short-story writer, a brilliant man and a very fine person,” who was considered for admission as the “eighth member to top leadership” in the Mattachine. “He was Third Order and had demonstrated competence as a leader. I remember that I personally felt he had accepted fully and completely the Mattachine philosophy rather too quickly and too unquestioningly […].”

The only surviving photograph of the Mattachine founders (asterisked), Christmas 1951. Pictured are Harry Hay (upper left), then (l–r) Konrad Stevens, Dale Jennings, Rudi Gernreich, Stan Witt, Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland (in glasses), Paul Bernard. Photo by James Gruber. The photographer, James Gruber, with Stevens,

became the sixth and seventh to be admitted. Considered for, but denied membership, Benard is said to have drowned in 1954 after

moving to Mexico. Hull's friend Witt sometimes socialized with members, as on this occasion. (Photo courtesy James Gruber)

Benard is portrayed as a dissident by another Mattachine cofounder, Dale Jennings. Regarding the unity platform as espoused in the first of the Mattachine’s three-point Missions and Purposes, Jennings writes, “Early in the movement, Paul Benard, whose name deserves to be correctly spelled, and others clearly saw that it was a make-do unity that was not based on actuality”. Writing earlier, under the name Jeff Winters, Jennings describes Benard as: a lively, electrically intellectual bisexual who should have been admitted to the Inner Circle. He wasn’t for two reasons. First, he believed that the only true normality was a heterosexual-homosexual balance and, second because the Inner Five wanted to remain in firm control. Paul laughed and said, “Judas, you guys, we’re not a minority! We don’t want to be a minority! Acting like one and trying to institutionalize homosexuality is exactly what the lynchers want us to do! The thing they hate most is not knowing who’s straight and who isn’t. They’d dearly love to have us stand up and be counted! After that, they’ll offer us a little plaque in the sidewalk in return for trooping down to City Hall (as they do in West Hollywood) to register as carnivores and sphincter-stretchers! Our only job as an organization is to point out to the world that what we do in bed is our own business. All we’re after is equal rights with everybody else. Once we get them, we’ll disband!”

For his part regarding Benard, Chuck Rowland wrote that “I was on the brink of voting for” him as number eight of the Fifth Order “when someone asked the question about the extent to which he was devoted to the Cause. We had, finally, to agree that he was far too interested in Making It Big as a writer to be given top responsibility in the Mattachine.” Odd, for it was Mattachine cofounder Rudi Gernreich who had left town for a job in New York in August of 1951, returning in November, the Mattachine’s first anniversary. Nevertheless, Rowland called the decision about Benard “one discussion in which we came the closest we ever did to dissension.” And Harry Hay placed Benard in the “cast of ‘characters’ for the Foundation/Society-Inner-Sanctum rolls.”

How Benard came to the Mattachine is disputed. Timmons writes that Ruth Bernhard brought him in, but Hay, writing in 1986, said it was the reverse. Hay said in 1976 that Bernhard’s involvement began in July 1951; in 1956 he wrote she became involved that September. Since Bernhard was teaching at a radio and television school when she is said to have come to the Mattachine via Philip Cary Jones, she and Benard could have met at the school, Benard having taught radio production in Arizona just before his move to Los Angeles. It’s also quite possible that Benard had come to know Jones via their work in Vanguard Stage in 1945.

Again, writing in 1956, Hay said that Benard had radical backgrounds whose severings were troubled with undisciplined and reprehensible behaviors. Hay, continuing: During his brief but tempestuous career on the Mattachine Olympus he was first married to Dale, then he allowed himself to be seduced by Bob into deserting Dale and marrying Bob.

Jennings’s breakup with Hull is thought to be the catalyst for Jennings’s nighttime stroll in 1952 leading to his arrest for “lewd and dissolute conduct” and the decision by the Mattachine to support one of its founders. But Hay, again writing in 1956, provides an account of machinations on the part of Hull that would have exacerbated any melancholy engendered by the breakup: The first act of the Paul-Bob alliance was a concerted effort to kick Dale out of the top Mattachine echelon. (It was during the rebound and aforesaid consequence that Dale’s personality began exhibiting emphatic signals of distress, climaxed by his “entrapment”.)

Just at the time Hull and Benard were attempting to marginalize Jennings, his legal case became a cause célèbre for the Mattachine, leading to triumph and, ultimately, tribulation when its growth was accompanied by demands for a new direction.

Days before Dale Jennings was entrapped by police on March 21, 1952, the Mattachine already was involved in another dispute regarding the LAPD. The Mattachine leaders had decided to participate in a March 17 hearing conducted by the city’s Police Commission regarding police brutality. Harry Hay recalled attending the meeting with all the Mattachine founders except Jennings—but with Paul Benard in attendance—and speaking as members of the Mattachine (but not as homosexuals) in sympathy with brutality victims, especially Mexican Americans entrapped by plainclothes police. The Los Angeles Times covered the Monday, March 17 hearing, listing more than a dozen civic, labor, and political leaders, without any mention of the Mattachine members. Dale Jennings’s arrest that Friday would cause a change of course.

Paul Benard is mentioned only once in conjunction with his ex-boyfriend Dale Jennings’s legal fight. Harry Hay recalled, “Paul […] opposed my project to transform Dale’s defense into a [homosexual] Minority-wide civic campaign,—and in the middle of the [Mattachine] fund campaigns he panicked off to Mexico.”

As early as 1952, even before its formation, ONE (the magazine’s eponymous corporation) already had a fellow traveler of sorts in Mexico, one from north of the border: Paul Benard. Paul Benard’s occupation on his death report was listed as “newspaperman.” He was a journalist, but not necessarily a prolific one, with only two articles—regarding Mexico tourism—indexed. “He was writing travel articles for American magazines,” Kepner wrote in late 1954, “getting an average income of a little over a hundred [dollars] a month, about a quarter of which he was saving toward buying a home.” Given that Benard’s first indexed article is titled “Mexican Month: $112” in reference to the amount he spent in the country’s capital, he may have been able to make do on savings supplemented by his income from writing. To begin with, as he reported in “Mexican Month,” the bus trip from the Texas border to Mexico City—36 hours and 1,346 miles—cost a mere $11.15. Having stayed in the capital for four weeks, Benard concluded, “Why, it’s cheaper to go on a vacation than stay home and work—and certainly much more pleasant and enlightening.” Matters of thrift aside, Benard began his travelogue on a note of social commentary, perhaps not all that common in the pages of Travel magazine, for which he wrote: Contrary to popular opinion, I didn’t see one Mexican in serape and sombrero, snoozing under a towering cactus, during the whole trip. Whoever invents these jokes about lazy Mexicans should watch the farmers in every village along the Central Highway, working in the fields in mid-afternoon with a piece of rough board for a plow.

Benard’s second article for Travel, “Janitzio: Where Time Has Stopped,” takes readers through the folkways of a jewel in the state of Michoacán. “The Tarascan artist, noted throughout Mexico for his delicately beautiful lacquer work, rarely exhibits his wares in Patzcuaro’s two public marketplaces,” Benard wrote regarding the town bearing the name of the lake surrounding the island of Janitzio. “But a few words to the local policeman—and a few pesos tip—will take the traveler through the quaint, cobbled sidestreets to the private homes of the region’s leading craftsmen.”

Six months after Benard’s profile of the island of Janitzio, he drafted a travel itinerary for the ONE emissaries—Chuck Rowland, Bob Hull, and Jim Kepner—who came by car to pitch the formation of an organization for homosexuals in Mexico City. Their route took them through Michoacán (Uruapan, bypassing Janitzio), where they met three amateur bullfighters aged 18–20, eventually taking the trio to the capital. Kepner had not yet met Paul Benard. “I had been looking forward to spending a few days in his apartment with more than a little fear,” he wrote two months after the trip, “expecting some damned impossible bitch, but he was really a wonderful person.”

Jim Kepner, writing two months after having been there, remarked, “For eighty [dollars] a month [Benard] was living just next to lavishly, with a four room modern apartment in a fine part of town, two solid walls of picture windows with balcony, full time maid who brought her sister in now and then to help her, and throwing parties about once a week.” So Benard, after two years, presumably would have had the sort of connections that, when conveyed, would motivate the ONE emissaries to their mission. In fact, upon the arrival of Rowland, Hull, and Kepner, Benard “threw a lavish party for us,” Kepner recalled, “with about forty guests, all Latin, though most of them spoke English. A mad party, and a wonderful party.”

Paul Benard drowned on November 7, 1954—just days after Hull, Kepner, and Rowland returned from Mexico. Benard’s friend Rafael Salinas, a furniture salesman, wrote Kepner on the day of the drowning: Jim: listen carefully: This afternoon Paul Benard, or, Charles Coté died drowned in the sea in Acapulco Guerrero. I went to see Fred Erickson who lives in Sonora #13 in this city to tell him, so he went to the Embassy to have his body brought to Mexico City. I believe the body will be cremated for this was his last will. I received a Telegram from the fellow he went with, vacationing to Acapulco name of Rodolfo Rentería.— Paul told me previously about your accident in Tepic. Please tell the Boys about this fatal thing. I have no way to express how bad I feel. I only do things by mind for I wish I wouldn’t have had to be the one to tell you this awful news. Let the Lord keep his soul, for he was one of the best friends I have ever had. He also told me last Thursday the 4th that he had to pick up your broken car back to you all. Please answer this letter. I hope you all are OK by now. Best wishes and please let me know how are you all. I believe the Devil is loose, so I will stay home a little longer.

The U.S. State Department issued a report on Benard’s death, stating he died at noon that Sunday at Playa Revolcadero in Acapulco. Despite any effort in removing Benard’s remains to Mexico City, they were interred in the “common cemetery” in Acapulco according to the official report. A telegram was sent to his father Charles Roy Coté, who directed Benard’s effects to be deposited with Mudanzas Gou, an international moving and storage firm. Benard’s occupation is listed as Newspaperman, and his last known address in the U.S. was South Pasadena.

Two years after the 1954 Mexico trip, both Rentería and Rowland would remember Paul Benard with flowers at the midnight service of Rowland’s Church of One Brotherhood, December 24, 1956 (COOB). Rentería had been coaxed by Rowland to join him in Los Angeles, but their liaison grew to be thorny.

My published books: