Partner Paul Levenglick

Queer Places:

Tanglewood, 297 West St, Lenox, MA 01240

Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum

Hartsdale, Westchester County, New York, US

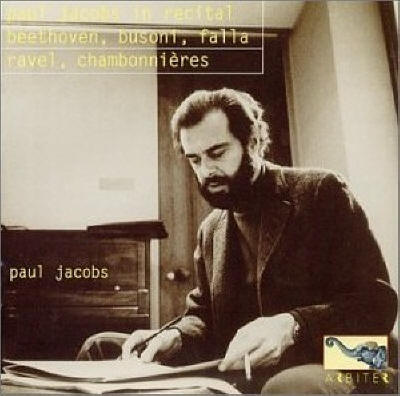

Paul Jacobs (June 22, 1930 – September 25, 1983) was an American pianist. He was best known for his performances of twentieth-century music but also gained wide recognition for his work with early keyboards, performing frequently with Baroque ensembles.

Paul Jacobs (June 22, 1930 – September 25, 1983) was an American pianist. He was best known for his performances of twentieth-century music but also gained wide recognition for his work with early keyboards, performing frequently with Baroque ensembles.

Paul Jacobs was born in New York City and attended PS 95 and DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx and studied at the Juilliard School, where his teacher was Ernest Hutcheson. He became a soloist with Robert Craft's Chamber Arts Society and played with the Composer's Forum.[1] He made his official New York debut in 1951. Reviewing that concert, Ross Parmenter described him in The New York Times as 'a young man of individual tastes with an experimental approach to the keyboard that he already has mastered.'[2]

He moved to France after his graduation in 1951. There he began his long association with Pierre Boulez, playing frequently in his Domaine musical concerts, which introduced many of the key works of the early twentieth-century to post-war Paris. At a single concert in 1954, which must have lasted close to five hours and also included works by Stravinsky, Debussy and Varèse, Jacobs contributed chamber music by Berg, Webern and Bartók and gave the première of a new work by Michel Philippot.[3] In a 1958 Domaine concert he played a work written for him by the 21-year-old Richard Rodney Bennett, his Cycle 2 for Paul Jacobs.[4] He acted as rehearsal pianist for the incidental music which Boulez wrote for Jean-Louis Barrault's production of the Oresteia in 1955.[5] Jacobs later said that meeting Boulez had put an end to his own composing ambitions: 'I just gave it up. I wouldn't have dared show anything of mine to Boulez.'[6] During his time in Europe he appeared as soloist with the Orchestre National de Paris and the Cologne Orchestra and made many radio broadcasts.[1] He played for the International Society for Contemporary Music in Italy and at the International Vacation Courses for new music at Darmstadt.[2] For the 1957 course, Wolfgang Steinecke invited him to give the European première of Stockhausen's Klavierstück XI, a key work in the development of 'controlled chance'[7] and this may have been at the composer's suggestion.[8] Like many musicians with a commitment to new music, his existence was frugal. For broadcasts he would be paid as little as $5, which went up to $25 when he played the premiere of the Henze Piano Concerto 'because of the special difficulty of the piece'. He lived in a hotel 'with a window facing a wall so that I had to go outside to see what the weather was. There was room only for a bed and a piano and a little alcohol burner to make stew on.'[6] Around this time he became a close friend of the French painter Bernard Saby, whom he described as an important influence.[9]

Tired of trying to live on $500 a year, he returned to New York in 1960 with the assistance of Aaron Copland who arranged for some teaching work at Tanglewood.[6] In November and December 1961 he gave a pair of Town Hall recitals, mixing Boulez and Copland, Stockhausen and Debussy. The New York Times described them as 'just about overwhelming ... make no mistake, Mr Jacobs is a virtuoso even in the traditional sense'.[10] He made his recital debut as a harpsichordist at Carnegie Hall in February 1966 with a programme which included Bach, Haydn, and Manuel de Falla's Harpsichord Concerto.[11] During the 1960s and 1970s he continued to give solo recitals and played frequently for the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. He performed with the Fromm Fellowship Players at Tanglewood, Gunther Schuller's Contemporary Innovations and Arthur Weisberg's Contemporary Chamber Ensemble. He taught at Tanglewood and at the Mannes and Manhattan music schools in New York. For the last fifteen years of his life he was Associate Professor of Music at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York.[1] Jacobs was the New York Philharmonic's official pianist (from 1961) and harpsichordist (from 1974) until his death. He held the post during the tenure of three music directors. He can be heard as soloist in Leonard Bernstein's recording of Messiaen's Trois petites liturgies[12] and both Boulez's[13] and Mehta's[14] recordings of Igor Stravinsky's Petrushka. He is the pianist in the NYPO recording of George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue (conducted by Mehta) used by Woody Allen in the opening of his film Manhattan.[15] He had a long collaboration with the American composer Elliott Carter, recording most of Carter's solo piano music and ensemble works with keyboard, including the Double Concerto for Harpsichord and Piano, With Two Chamber Orchestras, the Cello Sonata and the Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello and Harpsichord. He was one of the four American pianists who commissioned Carter's large-scale solo piano work Night Fantasies (1978–80), the others being Charles Rosen, Gilbert Kalish and Ursula Oppens (with whom Jacobs often performed two-piano works).[16] It was Jacobs who organised the consortium after he and Oppens realised that Carter's previous reluctance to accept a commission for a new solo piano work from one pianist might have been born out of a desire not to offend others.[17] He gave the New York premiere of the work in November 1981. All of Jacobs's Carter recordings were re-issued by Nonesuch in 2009 as part of a Carter retrospective set.[18] He also gave first performances of music by George Crumb,[19] Berio, Henze, Messiaen and Sessions[1] and commissioned Frederic Rzewski's Four North American Ballads in 1979.[20] Aaron Copland called him 'more than a pianist. He brings to his piano a passion for the contemporary and a breadth of musical and general culture such as is rare.'[2]

He died of an AIDS-related illness in 1983, one of the first prominent artists to succumb to the disease.[21] He was survived by Paul Levenglick, his lover of 22 years. At his funeral on September 27, 1983, Elliott Carter delivered a eulogy, recalling his friendship and collaboration with Jacobs dating back to the mid-1950s.[22] A memorial concert held at New York's Symphony Space on February 24, 1984 was attended by some of America's most eminent composers and interpreters.[23] The music ranged from Josquin to two new compositions dedicated to Jacobs (by William Bolcom and David Schiff).[24] Pierre Boulez wrote in the programme: 'twentieth-century music owes him thanks for all the talent he generously put at its disposal.' Bolcom included a lament for Jacobs as the slow movement of his 1983 Violin Concerto[25] and dedicated his Pulitzer Prize-winning 12 New Etudes to him. He had begun to compose them for Jacobs in 1977 and completed them after his death.[26] Jacobs was also one of the friends and colleagues commemorated by John Corigliano in his Symphony No. 1.[27]

My published books: