Partner Édouard de Max

Queer Places:

Pontcharra-sur-Turdine, 69490 Vindry-sur-Turdine, France

Pierre de Massot

(April 10, 1900 - January 3, 1969) was a French writer, linked to Dadaism and Surrealism. Pierre De Massot was in relationships with

André Breton and

Édouard de Max.

Pierre De Massot had an encounter with Glenway Wescott.

It is not known how Edward de Max met Pierre de Massot, his 31-year-old

younger partner, but a tender affection was to bind the two men. The latter

was present and assisted him on his deathbed: "It is to my beloved friend Edouard de Max, the illustrious Romanian tragedian, that I think especially. Having seen him die in October 1924, and on the last sigh, turning his face on the side of the wall to hide his agony from those around him, I will never forget the expression of his gaze and the impression I brought back from it." Massot will be painted by Picasso, Max Ernst, Picabia and Georges Malkine.

Pierre de Massot

(April 10, 1900 - January 3, 1969) was a French writer, linked to Dadaism and Surrealism. Pierre De Massot was in relationships with

André Breton and

Édouard de Max.

Pierre De Massot had an encounter with Glenway Wescott.

It is not known how Edward de Max met Pierre de Massot, his 31-year-old

younger partner, but a tender affection was to bind the two men. The latter

was present and assisted him on his deathbed: "It is to my beloved friend Edouard de Max, the illustrious Romanian tragedian, that I think especially. Having seen him die in October 1924, and on the last sigh, turning his face on the side of the wall to hide his agony from those around him, I will never forget the expression of his gaze and the impression I brought back from it." Massot will be painted by Picasso, Max Ernst, Picabia and Georges Malkine.

The sixth child of the Count and Countess of Massot de Lafond. His three brothers were killed by the Germans during the 1914-18 war. He had two sisters, one of whom was Genevieve, his twin. There is a 50-year gap between father and son. The father had no fortune; he was a simple thrift at the Hôtel-Dieu in Lyon. Pierre de Massot spent his childhood in a family home in Pontcharra-sur-Turdinne, in the Rhone. He studied at the Saint-Joseph Externat in Lyon, the current Lycée Saint-Marc. In several of his works, he has perpetuated the memory of Erik Satie, whom he knew through his Dadaist painter friend Francis Picabia. De Massot also devoted a monograph to Francis Picabia, published on the late of his life, to Seghers Publishing. Close to Jean Cocteau, Max Jacob and André Gide, of whom he was some time secretary, he was also linked with the painter Marcel Duchamp and the writer Tristan Tzara. Picabia got annoyed when he saw his young friend frequenting Cocteau: Pierre de Massot is a pretty butterfly that flutters with ease from flower to shit.

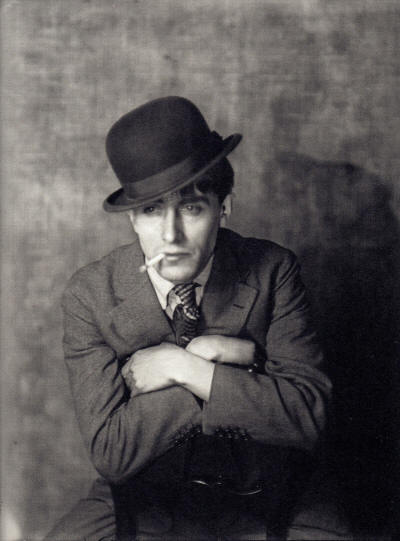

Pierre de Massot by Berenice Abbot

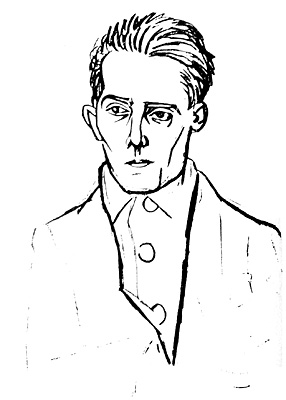

Pierre de Massot by Picasso

Pierre de Massot first met André Gide in 1922 at the Ballets Russes. He asked him to advise him on a novel he was writing. Gide was delighted to remove the 23-year-old from Cocteau's group. The correspondence (1923-1950) which was published by the Association of Friends of André Gide in 2001 thus begins in 1923. We read The letters of Massot as those of an admirer of love and tenderness, a bit like Andrée Hacquebaut of the Young Women, calling Gide "dear Master".

On July 6, 1923, a Dada party organized by Tristan Tzara, at the Michel Theatre, is heckled by the surrealists André Breton, Robert Desnos, Paul Éluard and Benjamin Péret. Pierre de Massot has a broken arm with a Breton cane, while Tzara appeals to the police. This evening, called the "Heart with a Beard" for posterity, marks the definitive rupture between Dadaists and Surrealists. Nevertheless, Pierre de Massot, who shared the revolutionary ideas of the surrealists, signed the manifesto The Revolution First in 1925. He published one-on-one studies on Saint-Just and Étienne Marcel that revealed his deep affinity with the thinking of André Breton's group. He published prose poems in the journal Manometer published by Emile Malespine in Lyon. He left the movement when he joined the French Communist Party in 1936. He left in 1956 during the Soviet invasion of Hungary.

Massot has a Scottish friend with whom he scrambled to end up marrying her. This lady was introduced to him by Man Ray. "Robbie, my only love after France and my flag," Massot wrote in "Foutaises," July 1924. He wrote half-word to Gide: "My dear Robbie, namely Miss Lila Robertson who played a big role in my life, who is the only woman I can bear and whom I will make known to you, for she can only seduce you (letter 27, March 30, 1928). On June 19, 1928, Massot wrote to Gide (letter 30): "I am writing to tell you one more secret thing: my marriage. And contrary to what one thinks at first, my freedom is increasing. I told you about a young English girl, Miss Robertson (...) We have known each other for 6 years and our love consists of a wonderful friendship (...) I entrust to you, alone, this: she knows what I love; herself likes what you know. His intelligence, which is singularly acute, leaves me with nothing to fear for the future. I just find a food for my loneliness. Unfortunately, when it comes to drugs, that is still a common thread. Yet I have high hopes that one day I will get out of it." On July 25, 1928, he married Lila "Robbie" Robertson, at the Church of the Madeleine. Jacques Maritain will be Massot's witness. They had one son, François de Massot. In a letter dated February 22, 1929 to Gide (letter 38), Massot writes: "Others will be amused to point out that I am united with an exquisite young woman whom I love without knowing what delicate and mysterious bond can embrace two hearts! And if they could assume that it is precisely to this soul, from which they hope my defeat, that I draw all my courage." His wife, to whom he was tenderly attached, died of a terrible illness in 1951. This death will plunge Massot into depression. After this death he wrote "heartbreaking" poems for her, including Visitation.

During the confused days of the Liberation in Paris, in 1945, Henry de Montherlant had asked Madame Elisabeth Zehrfuss (1907-2008) to warn some people in case something bad happened to her. Among them, Pierre de Massot. When one reads the first volume of de Montherlant's biography by Sipriot, he writes that Pierre de Massot was a "total" confidant of Montherlant. Montherlant quotes Pierre de Massot several times in his work and in particular in footnotes. However, he refers to Pierre de Massot in full text in his foreword to his play Malatesta. He confides that he spoke to Pierre de Massot about his play in 1944 before it was brought to the stage, and also in Le Solstice de Juin, where Montherlant recounts having seen with Pierre de Massot the parade of 600,000 Frenchmen on May 24, 1936 in the cemetery of the Pere-Lachaise. He concludes with this sentence: "My companion (Pierre de Massot) and I withdrew when the night was over. The parade continued, in the light of the newspapers lit as torches..."

During the war, he hid André Suarès, posing as his father. He was the one who led the writer's coffin in 1948. He also maintained fruitful ties with André Breton until his death. His homosexual experiences are recounted notably in his book My Body, This Sweet Demon (1959). Pierre de Massot was one of the signatories of the Manifesto of 121, subtitled "Declaration on the Right to Insubordination in the Algerian War", published in September 1960.

As he did not work, Massot was forced to join his parents in Pontcharra to survive. Picabia then offered to become the tutor of his two eldest daughters, which he accepted for a few months when he stayed in the Gaultret Castle inhabited by Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, in Tremblay-sur-Mauldre. He then returned to Paris and found a job with a bookseller. In 1961, he spent many months at the Sanatorium of Assy. In 1966, after André Breton's death, he fell into a deep depression that required hospitalization for several months. Pierre de Massot will end his life with his partner Micheline Kunosi who will allow him to live for a few more years. He died in extreme poverty in Paris on January 3, 1969, at the age of 68.

François de Massot, the son of Pierre de Massot and Robbie (Lila Robertson), will be a translator, a writer and a film industry. He was a believer in the extreme left, and had been close to Trotskyist circles since the end of the Second World War. He was a volunteer worker in Tito's Yugoslavia. Very close to the leaders of the International Communist Party, Marcel Bleibtreu and Pierre Lambert, he delivered the eulogy of Pierre Lambert at his funeral in 2008. He wrote a book on The General Strike of May-June 68 in France, published by L'Harmattan.

My published books: