Partner Bobbie Holmes

Queer Places:

Kinnerton Yard, 5 Kinnerton St, London SW1X 8EH, UK

Robert

Cunliffe "Robin" Ironside (1912 - November 2, 1965) was an English Neo-Romantic visionary painter. Despite having no formal training Ironside was one of the most individual artists working in Britain in the mid-twentieth centrury. A painter who was exhibited along side Paul Nash, Henry Moore and

Francis Bacon, Ironside was also a writer, illustrator and designer, Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery in London (1937-46) and Assistant Secretary of the Contemporary Art Society (1938-45). English art critic Brian Sewell described Ironside's work as "neo-classicism brought into neo-romanticism in beautiful alliance".

Robert

Cunliffe "Robin" Ironside (1912 - November 2, 1965) was an English Neo-Romantic visionary painter. Despite having no formal training Ironside was one of the most individual artists working in Britain in the mid-twentieth centrury. A painter who was exhibited along side Paul Nash, Henry Moore and

Francis Bacon, Ironside was also a writer, illustrator and designer, Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery in London (1937-46) and Assistant Secretary of the Contemporary Art Society (1938-45). English art critic Brian Sewell described Ironside's work as "neo-classicism brought into neo-romanticism in beautiful alliance".

The work of Broadway's gay and lesbian artistic community went on display in

2007 when the Leslie/Lohman Gay Art Foundation Gallery presents "StageStruck:

The Magic of Theatre Design." The exhibit was conceived to highlight the

achievements of gay and lesbian designers who work in conjunction with fellow

gay and lesbian playwrights, directors, choreographers and composers. Original

sketches, props, set pieces and models — some from private collections —

represent the work of over 60 designers, including Robin Ironside.

Robin died at 53, after a life devoted to the pursuit of art. After nine years as Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery, he gave it all up in 1946, driven by internal creative demons, to live in penury and devote himself to writing about art, and painting minutely detailed romantic pictures. He revived an interest in the Pre-Raphaelites almost single-handedly with his introduction to a book published by Phaidon, coined the term ‘neo-romantic’ in one of his many essays, and designed several opera and ballet sets, including Der Rosenkavalier in 1947, and, with Christopher

Ironside, his brother, Sylvia at Covent Garden in 1952. After his obituary in the Daily Telegraph, an anonymous contributor, probably Sir

Kenneth Clark, one-time Director of the National Gallery and Chairman of the Arts Council, wrote of Robin’s darker and more self-destructive side: “Conspicuous among Robin Ironside’s many talents was a talent for bad luck. If he did the designs for a theatrical production it was transferred to a new theatre at the last minute so that none of the scenery fitted or the management decided to cancel the production altogether; if he was an admirable portrait painter, his sitter became mortally ill and had to leave the country; if he collected his essays for publication, his publisher went bankrupt and lost the manuscripts. He belonged in spirit to France of the 1850s, to the world of Berlioz (whom he so strikingly resembled), Baudelaire, and Grandeville, but his lack of success was also the cause of his early death. Like Piero di Cosimo, he used to go for days with no food except a few boiled eggs.”

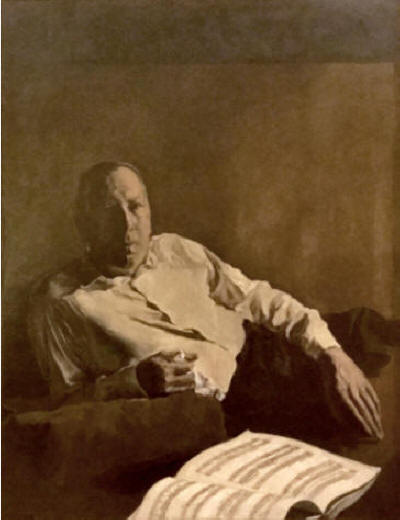

Robert Cunliffe "Robin" Ironside and Alan John Ross by

Rollie McKenna

Graham Eyres-Monsell

Date unknown

Oil on canvas

Size unknown

Private Collection

Portrait of Colette Clark

c.1958/59; exhibited 1966 (No.3)

Oil on canvas

90.2 x 69.8 cm

Private collection

The Flaying of Marsyas

Exhibited 1957

Oil on canvas

105 x 150 cm

Private collection

Robin loathed his public school, Bradfield College, in Berkshire. A contemporary reported that Robin had once been held down on a table and raped by an older boy while others watched. True, the friend was notoriously unreliable, but something very nasty almost certainly happened to Robin in Bradfield’s woodshed. He detested the place and never mentioned it in Who’s Who. “The idea of razing the establishment to the ground and sowing the site with salt gave us both pleasure and spiritual refreshment,” said my father, later. Having failed to get a position at the Foreign Office in the Diplomatic Service – the problem was maths, for which he got one mark for neatness – Robin, aged 17, went to Grenoble to learn French. From there, he attended the Sorbonne. He then toured Germany where he met

Maurice Bowra. It was during this period that he became fluent in both French and German.“Robin was a wonderful sightseer,” said Bowra. “He would miss nine things but when he came to the tenth he would be fascinated by it. It was he who said you must never spend more than one hour in a museum and never see more than five things and you’re lucky if you see that number. Quite right.” Robin then attended a course at the Courtauld Institute of Art, and eventually landed a job at the Tate Gallery as Assistant Keeper in 1937, becoming number two under the Director, John Rothenstein. Sir Maurice Bowra, Warden of Wadham College, Oxford, said: “Johnny Rothenstein was like a great big Cheshire Cat. He was a great figure of fun at Oxford who always turned up at parties unasked. He seemed to appear through the walls and then back through them. His father was the same apparently.” Rothenstein was a tiny, shrivelled monkey of a figure with an ape-like grin.

Rothenstein recalled how he first met Robin Ironside: “Well, I arrived at the Tate, and Fincham, who was the senior of my two assistants who was a quite frightful man, introduced me to everyone except Robin. He, Fincham, then declared he was going on holiday the next day, just when I most needed him. So I looked around for someone to help me and came across this pale and unconventionally elegant young man of 26. I said: ‘Who are you?’ and he said: ‘My name’s Ironside.’ ‘And what are your duties?’ I said. ‘I haven’t any duties,’ he replied. ‘The day I arrived Fincham came into my office, shut the door, stood with his back to it and said: ‘Look here, Ironside, nobody wants you here so just stay in your office, keep your nose out of what doesn’t concern you and keep your bloody little mouth shut.’

So I had nothing to do except read Baudelaire and look at paintings and write the introduction to the catalogue for the Constables since there was no one in the gallery literate enough to write it. But apart from that I’ve done nothing at all and scarcely a word has been spoken to me. I didn’t do badly at the Courtauld, but my real education has been in this office. It’s an opportunity that doesn’t often occur, I suppose, to read for a year almost without interruption.’ And from that moment began a marvellous friendship with a man whose wit and learning was a constant delight.”

Even then, Robin’s behaviour was idiosyncratic. His brother

Christopher once said that during a Thames flood, the entire staff of the Tate was involved in trying to rescue the pictures in the basement. Wading through a long corridor Robin saw a young woman at one end struggling with some Turner drawings. To her consternation, she tore one by accident. Looking furtively around and seeing no one, she screwed it up and threw it away into the water. Robin was too astounded to do anything about it. Robin was sharing a bedsitter with

his father in Exhibition Road, near the museums in South Kensington, and he would return from the Tate dressed in a long black overcoat and black hat with a briefcase and an umbrella; but walking back from South Kensington station he always carried a small brown paper bag. This contained a Walnut Whip, which was eaten on arrival home with almost ritual solemnity. After dinner he would write and paint far into the night.

Nine years later, after the war, there came a moment when Robin’s loathing for the bureaucracy of the Tate and his passion for writing and painting set up an unbearable conflict inside him. He became increasingly driven, and art alone dominated his life. “The administrative needs of this very important but unhappy institution are such that, within its doors, I must largely renounce the pursuit of knowledge and that official occasions for enlarging my appreciations elsewhere hardly, if ever, occur,” he wrote. He became critical of the world in which he worked. He wrote: “Museum directors who, in their natural eagerness to compensate for their predecessors’ exclusive support of an obsolete representational manner, are perhaps unaware that to purchase a picture because it bears no resemblance to nature or because its resemblance to nature is perfect may be two courses equally mistaken.” He suggested to the Tate that they raise his salary to a decent wage, saying he’d leave if they didn’t; and when they did he resigned all the same. He argued in the monthly magazine, Horizon, in 1944, that the scandal of the Wilde trial and the early death of Beardsley had cut short the imaginative tradition which, he wrote: “had been kept flickering in England since the end of the eighteenth century, sometimes with a wild, always uneasy light, by a succession of gifted eccentrics.” He moved into a minuscule, freezing and wretched flat in Clarendon Street, a row of tiny peeling Victorian houses in a little road behind Victoria railway station. It has never become gentrified and is a grimy backwater full of dingy hotels. “The flat was tiny and messy but it didn’t smell because Robin was very hot on smells,” said

his sister-in-law. “He was a tremendous bather – he’d have about three baths a day. I remember him once saying, ‘I don’t smell do I?’ He had a tiny kitchen and a bathroom with a lavatory and no seat. And he always used George Dix’s father’s winding-sheet as a dressing-gown.” (George Dix was an influential New York art dealer.) “Of course I enormously regretted his leaving the Tate,” said John Rothenstein. “He’d often said to me that he painted and I had always thought rather vaguely, oh, he’s probably one those intellectuals who thinks he can paint but of course I was astonished when I saw these beautiful paintings, I was amazed at the beauty of them. As soon as I saw them I believed them to be the product of a minor but extremely rare and esoteric talent – a talent deriving nourishment from classical and baroque sculpture, from Gustave Moreau, Moore, Beardsley, the early Surrealists and Dali, but strong enough to assimilate many influences and to fuse them into a highly personal art.”

To execute his immensely detailed paintings, Robin often used a magnifying glass. His favourite painters were

Duncan Grant,

Roger Fry, Matthew Smith, Stanley Spencer, David Jones,

Edward Burra, Henry Moore, Samuel Palmer, and James Ward, and he was greatly influenced by John Piper, John Martin and perhaps Fuseli, classical sculpture and early Greek painters like Apelles, Polygnotus and Zeuxis. But the subjects of his own pictures were nearly all totally imaginary, usually with literary, scholarly or classical themes. In some there are hidden allusions which are neither evident nor easily interpretable to any onlooker but a classical scholar.

In his biographical notes to British Painting Since 1939, he announced various artists’ lack of training with the same fanfare as if they had received triple-firsts in draughtsmanship. Of

Francis Bacon he wrote: “Largely self-taught.” Of

Lucian Freud: “Mainly self-taught.” Frances Hodgkins: “Attended no art schools.” Victor Pasmore: “Attended no art schools.” Of Balthus he wrote (in Horizon in 1948) that “happily he was never a student at any art school. It is a modern commonplace that the poetic faculty cannot be acquired by study, yet, though painting has no agreed public functions, though the best modern painters have been concerned with communicating mysteries to initiates, and though the hermetic quality of fine art is not today wrapped in veils of equivocal intelligibility, intending painters are still encouraged to learn their art in schools. Here, at an age when they must be inclined to emulate in some degree the appointed authorities in their chosen profession, they may acquire some useful mechanical knowledge; but they will certainly be stuffed with precepts, portents, possibly in the minds of their teachers, but not necessarily of the slightest value elsewhere. Where it is a question of fine art as opposed to applied art, schools devoted exclusively to the training of painters for the production of works of art are of negligible, if not of ill-omened, significance.”

Sometimes the brothers worked together – Robin designing and Christopher executing

Frederick Ashton, Margot Fonteyn and Robin on the set of ‘Sylvia’ Memorial obelisk for Ian Fleming in Sevenhampton churchyard, 1964 the drawings. Along with various designs for scenery and costumes for ballets and operas, they designed the huge coat of arms which was the centrepiece of Whitehall’s Coronation decorations and one year they also designed the setting for the Ideal Home Exhibition, Robin having conceived a giant classical chariot with horses which leaped out above all the bungalows at Olympia threatening, it seemed, to stampede all the visitors beneath their hooves. Together they designed the half-crown postage stamp commemorating the Shakespeare Festival in 1964. “His contribution (and drawback) was that his ideas were not inhibited by any consideration or knowledge of how they could be realised in three dimensional terms,” wrote

Christopher Ironside, who often became maddened by Robin’s lavishly impractical designs. “I had to take on this part of the work whether the design originated with him or me: but as there was a mutual, but unspoken, taboo against quarrelling. I would modify his work with impunity and he had no hesitation in altering mine. Sometimes a design drawing would go back and forth between us each trying to supply what the other couldn’t manage. What made him very difficult to work with was his perfectionism. I suffer from this badly enough, but with Robin it was maniacal. He found it almost impossible to meet a deadline. He consulted his doctor as to whether he might be cured or relieved of this perfectionism by hypnosis. The doctor said it was unlikely and that Robin would probably put the hypnotist unwittingly into a trance himself. “Once when we were designing one of our stage design jobs we were already several hours behindhand for an appointment to deliver some work to the scene painters (and weeks behind time for the whole thing). We went by taxi (of course) and on the journey Robin was still painting a small bit of forest that showed through an open window on the set. On arrival at the studios, Robin continued to sit in the back of the cab painting away with a large drawing-board on his knee. I was hopping about out on the pavement counting my money as the clock on the taxi kept clicking up the fare and shouting at Robin: ‘For God’s sake stop! No one in the audience can possibly even see the bits you are now painting!’ This scene of urban bohemian life came to an end by my sweeping away the jar of paint water he’d brought with him in the cab and emptying it into the gutter.”

Apart from illustrations for his friends’ books, Robin carried out a variety of other commissions, from Rococo wallpaper for a music room to murals, usually for the benefit of rich friends who would patronise his work. For instance, he was commissioned by Ann Fleming to design a four-foot obelisk as a memorial to her husband Ian. It stands in Sevenhampton churchyard in Wiltshire. His over-excessive attention to detail did, however, slow down his rate of production. Often the owner of a country house in which he spent a weekend would hear a sinister rustling in the middle of the night, and come downstairs with a poker in hand only to find Robin, next to a wall, working by the light of a torch, obsessively touching up a picture that he had sold to his host years before. Yet, despite his slow rate of production, he did succeed in having fourteen exhibitions during his lifetime – including one at the Hanover Gallery in 1949 with Francis Bacon. On one such country house weekend Robin had been recommended a patent medicine called Dr Collis Browne’s Chlorodyne and had become addicted to it. Chlorodyne was a mixture of laudanum (an alcoholic solution of opium), tincture of cannabis, and chloroform. Robin used it for prolonged sessions of work throughout the night. It is difficult to say how much drugs influenced his obsessive behaviour and, indeed, the bizarre and darkly imaginative scenes he created in his work. His addiction became so great that he was constantly having to change chemists to get his supplies lest they become suspicious. “I remember Robin coming down to stay with a mutual friend in Dorset and there was this terrible snow storm and of course he brought his Collis Browne with him,” said Colette Clark, Sir Kenneth Clark’s daughter. “But then we got snowed up and Robin got more and more peculiar. I mean now I can see it was drug-withdrawal and we thought it must be because he couldn’t get his Collis Browne. He was quite irrational and mad. Anyway this friend took him upstairs to go to bed and watched over him all night and in the morning, I don’t know how we did it, but we got a taxi to take him to the station and just pushed him onto the train. I have no idea how he got back to London – God takes care of the sick! – but that night we had a call and it was Robin who was perfectly all right of course. No doubt he’d got more Collis Browne.” After that he would never travel anywhere without packing at least half a dozen remedies, each wrapped in tissue paper to prevent one from contaminating the other. “At night he used to take at least a dozen preventative measures for half a dozen different ailments,” said John Rothenstein. “Not that he’d ever walk or swim to keep himself healthy. No, that kind of thing was complete anathema to him.” “Robin was always interested in drugs,” said a doctor contemporary of his,

Patrick Trevor-Roper. “He was obsessed with mental distortion, he had a marvellous free-flowing conversation with his bright, inquisitive mind and his rapid conversation. He was interested in psychopathies and mental deviations and quirks and schizophrenia.

There is a picture he painted, Depressed People Waiting for a Lift. For long periods he was on heavy doses of amphetamines like Benzedrine – I wasn’t sure how much his bird-like mind was due to the amphetamines or its true nature. I tried to rail at him against it but it was impossible, he knew all the answers, he was always ready with them. He would say that they gave him enhanced perception, suited his psyche and that he took them for positive reasons rather because of a negative dependence. He certainly always had very dilated pupils, which might have been result of the amphetamines of course. “One day he asked me to have an evening with him taking mescaline and LSD. I think it was

Gerald Heard – a strange esoteric philosopher – who’d sparked the idea off with a letter to

Raymond Mortimer, who was editing the New Statesman at the time. He implied that when he’d taken it, he’d seen God, although he was of course a convinced atheist – this was long before

Aldous Huxley had written his book, of course. “I got, without any difficulty, some mescaline from the hospital where I worked saying it was for medical research and Raymond and I took some. We didn’t know how much to take or anything. I had a medical student handy in case things went wrong. We took far too much, knocking it back and I was very ill, with a temperature of 107. Then Raymond wrote an article about it for The Times and I think that was how Robin became interested and said: ‘I must have it’ so he and I took some and this time I got it from the hospital again, I can’t remember how, but we knew the right dose, roughly, anyway. Robin gave me dinner at the Jardin des Gourmets and as I dropped him off at Pimlico we parted and said what a pity it seemed to have no effect at all, and I said I was awfully sorry. But as he later told me, as soon as he had shut the door to his flat and was on his own (because this is how the drug works – the presence of other people often inhibits its effect) he was astonished at the myriads of colours he could see and he said he saw the most wonderful textures in the folds of the curtains and the most beautiful colours and walked round Victoria Station and found it exciting, picaresque and romantic – in a funny way an altogether a compelling experience. He also had the utmost difficulty in preventing himself from clutching passers-by in order to point out the ineffable beauty of St George’s Hospital at Hyde Park Corner at night. He said it looked like a gigantic quinquireme floating in the sky with every window lit up in a different colour. “Then he said: ‘Let’s have some more.’ I think it was LSD this time. It was about six months later. We had supper and then went to some louche queer bar down the Fulham Road and all our friends later told us how oddly we were behaving because we were totally absorbed in ourselves, and we then went home together thinking how boring other people were and how exciting our own world was. But when he was alone he told me later it had a greater effect on him and he was tempted to take a taxi down to the Thames and every few moments he stopped the taxi and had a good look at the river, excited by its colours. “On the fourth occasion, when he stood transfixed by the wonder of it all, leaning for some time over the parapet, the taxi still ticking away by the kerb, he heard the driver calling out: ‘Don’t do it, guv. Go home to bed. It’s not worth it. Life’s too good. Things always seem better in the morning.’ And Robin had the greatest difficulty in explaining to this kind man that he wasn’t considering committing suicide.”

Robin was always chronically short of money. In 1953 he wrote in answer to

a questionnaire entitled ‘The Cost of Letters’ in Horizon: “I require, for the

satisfaction of my aspirations and having due regard to the present cost of

living, a net income of £15 a week, an amount I have never possessed and am

never likely to possess … Because I am too poor,” he added, sadly, considering

his extensive knowledge of Greek Classical history, poetry and myths, “I have

never been to Greece.” His only extravagances were taxis and the occasional

meal out.

Robin’s enormous anxieties about money, however, were partly answered. In 1960, just when he was at the end of his financial tether, his father died. Reginald had been struck off as a doctor but had got a job as a private anaesthetist. One of his patients was a hideously unattractive millionairess called Dolly. The moment this wealthy creature woke up from an operation for which Reginald had administered her anaesthetic, she saw the stunning good looks of

Robin's father staring down at her and decided to marry him. He spent the rest of his life in a mock-Tudor house in Esher, kept on an extremely tight rein with a very small allowance and never allowed up to London except in the company of her chauffeur, who dogged his every move. Thus the wicked Reginald got his come-uppance and, when he died, Robin got his reward in the form of a small legacy from his rich stepmother. He sold the last two years of the lease on his Clarendon Street flat and, on the proceeds and his stepmother’s money, he scraped up enough to buy the lease of a tiny flat in Kinnerton Yard in Knightsbridge which he painted a dark, shiny blue. Upstairs on his roof garden he tried, like Rex Stout’s great fictional hero, the detective Nero Wolfe, to grow tropical plants and orchids – in vain. Here he continued to paint and write through the night and read or sleep during the day. In her diary Ann Fleming wrote, on Monday 12 October 1959: “On polling day my first task was to collect a dropsical centenarian and his wife who live immediately opposite Robin Ironside. She was very maternal about Robin for the poor pair do not sleep well and wonder why the young painter’s light is always burning at all hours of the night. I immediately called on Robin who went whiter than his wont and said: ‘What else did she tell you?’ I fear I added to his general condition of anxiety.” Robin’s obsessional qualities hampered him as much in his writing as in his painting. Maurice Bowra told that

Cyril Connolly, the editor of Horizon, always thought that Robin was fearfully erudite but not a natural writer, but for Robin, poetry, writing and painting seemed to be inescapably intertwined.

In his preface to Pre-Raphaelite Painters there are quotations from Rossetti’s poems woven into the text which are difficult to spot because they appear to be part of the natural flow of his sentences, and he sometimes included lines from Tennyson in his prose. “It was, at first, as if the Brotherhood looked at the world without eyelids; for them a livelier emerald twinkled in the grass, a purer sapphire melted into the sea.” In ‘England’s Poets in Paint’ in Art News of October 1950, he wrote: “The history of English culture is largely a history of the achievements of poets, and there was no English school of painting comparable with anything that had been produced on the continent until English poets turned to the contemplation of natural forms as a chief source of inspiration. The paintings of Constable and Turner are, as it were, spontaneous versions in another medium of those passionate depictions of landscape in which the works of Wordsworth and Shelley abound.” About Paul Klee he wrote: “The art of Klee may be heard before it is seen; there is a throbbing of gold and silver wires, a loosening of notes, that fall upon the ear larghetto and whose delicate amplitude of sound is perpetually renewed among a thousand subtle and capricious discords.” And he wrote, in reply to criticism of his style in The Month in 1949: “You say that my style is exotic; but this element, and what various reviewers described as the preciosity of my language, is I believe due to a device which is the very reverse of exotic in the literal sense of that word. In my endeavour to convey the essential flavour of Pre-Raphaelite art, I made a diligent study of Pre-Raphaelite poetry and whole paragraphs of my essay are composed of a mosaic of phrases, metaphors, and sometimes entire lines from the poetry of Christina, Dante Gabriel, Morris, etc., pieced together with great labour to form, I hope, a harmonious prose entity.”

After Robin’s death, an entire edition of Apollo was devoted to him, and six of his articles were reproduced. A critic, writing in this edition, commented: “He could have been found among the poètes maudits of the fin de siècle or, perhaps, at some small German Rococo Court, where his strain of fantasy would have been appreciated by a ruler of like artistic caprice; nor would he have been out of place designing sets for Ludwig of Bavaria. His intense feeling for art was adequately matched by his intellectual prowess.” He was, however, never snobbish or pretentious in his writing or his encounters in the literary world. Robin’s friend Diana Witherby said: “I always remember him taking me to lunch with the author

Ivy Compton-Burnett and saying, typically: ‘Do remember to be nice to

Margaret Jourdain because since Ivy has become so famous she feels very out of the limelight.’ Margaret used to be a very famous expert on furniture and Ivy was just her friend you know, scribbling away and then suddenly it was Ivy who became successful and I think Margaret rather felt this.”

Unlike most of his contemporaries he was a fan of neither

T.S. Eliot nor

W.H. Auden (“complete frauds”), but he could, and did, discuss with equal vigour the merits of Virgil, the intricacies of the plot of a crime novel, and a short story by P.G. Wodehouse. Robin was extremely social – partly as a matter of necessity, for he would have found it hard to live without the patronage of well-off friends. Luckily, with his quick-silver charm, intelligence and courtesy, he was much sought-after as the extra man in the beau monde, or as a guest at a country house-party – but he would rarely go out of the house when he got there. Sir Kenneth Clark wrote of Robin: “His slender figure and rather exquisite clothes – these were wildly eccentrically elegant, but he had to dress cheaply – his pallor and elegance, his immense social gifts all suggested an aesthete to whom the open air was deeply repugnant.” He would often be asked as a last minute guest by the society hostess, Lady Emerald Cunard, Ann Fleming, Sir Edward and Lady Hulton or Lady Clementine Beit, but he would also stay frequently with Sir Kenneth Clark and his wife. He was, it was said, in love with their daughter Colette; certainly they had a very intense friendship. Or he would stay with another very close friend,

Graham Eyres Monsell, the brother of

Joan Leigh Fermor,

Patrick Leigh Fermor’s wife. “I always remember he never read the daily papers or listened to the radio or watched television,” said Joan. When dining out grandly Robin wore a double-breasted jacket, black jeans and black espadrilles. With a white shirt and a black bow tie he looked acceptable by artificial light; or so he claimed. John Rothenstein once persuaded him to become a member of the Athenaeum, “but I think he once came in wearing no socks or something and was frozen out. He was quite a socialist too, you know, in his velvet suits.” “I was terribly envious of him because he knew so many clever people,” said

his sister-in-law, who after her career as a dressmaker became Professor of Fashion at the Royal College of Art during the

1960s. “I remember him coming round and telling of having dinner with people like the famous fashion historian James Laver and thinking how I’d give my eye teeth to have lunch with James Laver.”

Robin also moved in more intellectual circles. As well as with Cyril Connolly and Maurice Bowra, he was very friendly with the writer

Angus Wilson. It was he who was responsible for getting Angus Wilson first published because he was so enthused and impressed by his stories that he took them to Connolly at Horizon who promptly printed them. On one occasion he sat next to

Evelyn Waugh, who wrote to Ann Fleming: ‘If you see Mr Ironside please chide him about his wrong opinion of Holman Hunt’s Shadow of Death (which he misnames Shadow of the Cross). I went to visit it in Birmingham last week – of course it is in the cellars – and found it a superb painting. The shadow on the legs is stunning. Had he examined it when he wrote so foolishly? He seemed to me a respectable young person and I am deeply shocked.”

“One occasion when staying away with friends for the weekend he had intended to leave on Monday morning,” said Diana Witherby, an old friend of his. “He was offered a lift back to London if he would stay until Tuesday. This would save him the railway fare: but he knew that Sir Oswald Mosley would be a guest for dinner on Monday. Should he spend the money for the fare and escape or save the money and have to shake hands with Mosley? Pressing financial necessity persuaded him to stay and shake hands but he always doubted whether this was an honourable decision. His clothes – he wore long, lineny, beigy jackets and a bow tie – like

Peter Watson, very elegant.”

Robin’s two greatest loves were Graham Eyres Monsell and Colette Clark. Graham was an elderly and charming bachelor with a long upper lip. He lived most of his time in the country except when he came up, Wednesdays and Thursdays, to his house in South Eaton Place in Belgravia. At one time he had taken a course in America to be a psychoanalyst, and had also reached near concert-pianist heights in Paris. His house was theatrically decorated with dark paintwork. On the hall-landing there was a golden table held up by a golden cherub, a couple of exquisite chairs and a huge vase of flowers on top of the piece, silhouetted against a window swathed in rich velvet curtains. The drawing room was a murky red, so dark you could hardly see, and the walls were packed with Robin’s pictures, including The Flaying of Marsyas, with Apollo preening himself in the background.

For a time, Ironside dated Bridget Parsons. Lady Bridget Parsons, something of an eccentric intellectual, was the daughter of the Earl of Rosse and a great friend of Robin’s at one point. With Christopher, Robin designed a fire-screen for her. A part-time friend was

Hugo Williams, the poet. They

first met at the London Magazine offices. It turned out they had lived near each other in Kinnerton Yard. “I always thought Robin looked iller every time I saw him. But he was so good-looking. He always seemed to me to be a rather lonely person. I remember his tiny flat in Kinnerton Yard and him showing me his studio and the pictures and quite honestly I thought they were awful. Oh, he was hooked on Collis Browne was he? That explains it. They’re very acid-trip pictures, really, aren’t they? They seemed to me to be just like architects’ drawings, just columns and pediments. I always felt a bit ill at ease with him. But I was at a stage in my life when I thought really good relationships were ones which made you feel ill at ease.”

Gradually, Robin did indeed look iller and iller. He apparently wanted to live for as long as possible, but he was burning himself out with non-stop creative activity. He never took care of himself, he smoked over 60 cigarettes a day, stayed up till all hours and slept less and less, he took drugs, had irregular meals which resulted in him getting progressively thinner, giving his eyes a nervous, glittering look, and he suffered regularly from acute indigestion. “Of course you know it was me who put the old boy onto Dr Collis Browne’s Chlorodyne, don’t you?” Maurice Bowra had said to me. “I was staying with the Clarks and he was suffering terribly from indigestion so I said, try this, old boy, and he adored it. You know you can get it without a doctor’s prescription. A lot of people say I killed him, but I think I saved him a lot of pain for ten years.”

After Robin died of an heart attack, his brother Christopher got the a letter from Angus Wilson: “Dear Christopher, Robin’s death has been the greatest shock to me so that I can form some idea of what a horrible loss it will be to you to whom he was so close. I owed him a great deal – directly, as I have written in The Wild Garden, my first appearance in print, more indirectly one of the most stimulating, loyal and valuably critical friendships I can ever hope to know. Robin was so rare a person for me – intensely interested in so many things I cared about, so awake to their relevance to each other, so not impatient but dismissive of all nonsense and cant. He was also a natural 19th century dandy – not the false kind that is so common to meet now. As a result one often had the curious feeling of hearing somebody witty and elegant who was able to speak out of two centuries at once – his own and France in the last century. He was so funny too and intensely aware of personal values and of the importance in them of shades of meaning. His death has made me sadder than usual at such times because he has so often told me of his wish to live as long as possible and also because in the last years he was living with a certain agreeableness that must have been a delight to him. I wonder if you ever saw him talking with me on tele about artists in novels. It was a very idiosyncratic performance and to those who knew him very endearing …” But then Angus Wilson dropped his bombshell. “In the last two years Robin had also been made very much happier because of his friendship with Bobbie Holmes. I simply do not know how much you know about this so please forgive me if I tread where only angels should. But Bobbie whom I only know a little is a very simple, tho’ lively young man who made a lot of difference to Robin’s life. Robin had helped him to go to night school and to get out of a dead end tho’ entirely respectable existence. Forgive me if I cause offence by writing all this but I can only think at the moment of what Robin would have wished and I am sure he would have wanted you to contact Bobbie now when he is feeling so very lost.”

It turned out that Holmes had been a waiter at Wheelers in Kensington, a branch of the fashionable fish restaurant, and that Robin had looked after him like a son. They had been planning to live together in a house in Gunter Grove when Robin died.

Bobbie was hastily hustled off the scene with a few measly mementoes and

perhaps some small sum of money, never to be seen or heard of again. Although

a few of Robin’s pictures are kept in museums, they’re rarely seen and most of

them are in private collections. One of his friends keeps her picture hidden

behind a door because she finds it so creepy.

My published books:/p>

BACK TO HOME PAGE

Robert

Cunliffe "Robin" Ironside (1912 - November 2, 1965) was an English Neo-Romantic visionary painter. Despite having no formal training Ironside was one of the most individual artists working in Britain in the mid-twentieth centrury. A painter who was exhibited along side Paul Nash, Henry Moore and

Francis Bacon, Ironside was also a writer, illustrator and designer, Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery in London (1937-46) and Assistant Secretary of the Contemporary Art Society (1938-45). English art critic Brian Sewell described Ironside's work as "neo-classicism brought into neo-romanticism in beautiful alliance".

Robert

Cunliffe "Robin" Ironside (1912 - November 2, 1965) was an English Neo-Romantic visionary painter. Despite having no formal training Ironside was one of the most individual artists working in Britain in the mid-twentieth centrury. A painter who was exhibited along side Paul Nash, Henry Moore and

Francis Bacon, Ironside was also a writer, illustrator and designer, Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery in London (1937-46) and Assistant Secretary of the Contemporary Art Society (1938-45). English art critic Brian Sewell described Ironside's work as "neo-classicism brought into neo-romanticism in beautiful alliance".