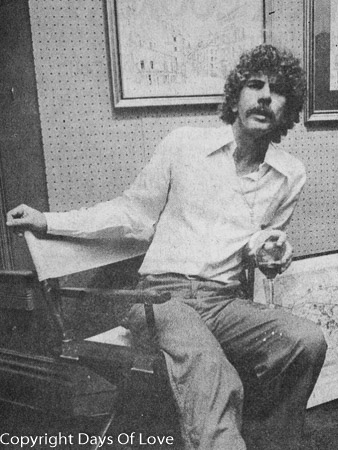

Robert Miles Parker (August 22, 1939 - April 17, 2012)

was a free-spirited artist who sparked an

architectural preservation movement in San Diego and translated the

personalities of Los Angeles and New York into distinctive pen-and-ink

drawings of their buildings.

Robert Miles Parker (August 22, 1939 - April 17, 2012)

was a free-spirited artist who sparked an

architectural preservation movement in San Diego and translated the

personalities of Los Angeles and New York into distinctive pen-and-ink

drawings of their buildings.

Parker published three collections of his drawings, which include

"Images of American Architecture" (1981), "L.A." (1984) and "The Upper

West Side: New York" (1988). The buildings that inspired him were

sometimes famous landmarks, such as Hollywood's Capitol Records Tower

and Pasadena's Gamble House. But more often, his sense of whimsy,

history and beauty led him to lesser-known subjects, many of which

have disappeared.

The urge to preserve grabbed him one day in 1969, when he

discovered that an abandoned redwood Victorian in his downtown San

Diego neighborhood was about to be leveled for a parking lot. He

tacked up a sign that read "Save This House" and added his phone

number to it.

To his surprise, he later recalled, "evidently a whole lot of people

felt the way I did." Shortly after he posted the sign, about 50 of them

crowded into his home to strategize about the 1887 structure known as the

Sherman-Gilbert house, owned by a prominent family that hosted

performances by artists such as dancer Anna Pavlova and pianist Arthur

Rubinstein. San Diego's Save Our Heritage Organization was born.

The city's oldest and largest preservation group, it has rescued many

historic buildings, including the Sherman-Gilbert house and several others

of similar vintage that have been restored and relocated to a "Victorian

preserve" called Heritage Park in San Diego's Old Town.

"Robert Miles Parker was preservation in San Diego," said Carol

Lindemulder, a founding member and past president of Save Our Heritage

Organization. "People flocked around to be with him. He gave a new

perspective on an old world."

A flamboyant personality who was more of an instigator than an

organizer, Parker provoked others, like Lindemulder, to drive the

campaign.

Parker "was good at inciting people," said Welton Jones, the San Diego

Union-Tribune's former critic-at-large. "Ultimately he changed the city in

his own way. He definitely was an agent of change."

Known to his friends as Miles, Robert Miles Parker Jr. was born in

Norfolk, Va., on Aug. 22, 1939. After his father died, his mother married

a Navy sailor and moved to San Diego, where Parker grew up.

After studying art at the College of William and Mary in Virginia and

earning a master's in art education from San Diego State College in 1963,

he taught junior high in Carlsbad and adult school in San Diego. In his

free time he recorded the "visual glories" of San Diego's Victorian

relics. He lived in one of them, which was located around the corner from

the Sherman-Gilbert house.

Later, as an art therapist in a mental health clinic, he often advised

clients to indulge their fantasies. In 1974, he decided to take his own

advice and embarked on a cross-country tour, making drawings of buildings

that captured his imagination. The results were collected in his first

book, "Images of American Architecture."

In the 1980s, he shifted his focus to Los Angeles and, finally, to New

York, where his renderings of theaters led the New York Times to compare

him to Al Hirschfeld, the renowned caricaturist of Broadway stars and

Hollywood celebrities.

"My way of understanding the city was simply to look at it," Parker wrote

in "L.A.," a collection of 195 drawings accompanied by his wry commentary.

Sitting in a director's chair with his drawing board on his lap and his

Norfolk terrier at his side, he used an old-fashioned dip pen and ink pot to

make art amid the distractions of urban life.

"Of course, you … swear because the pigeons fly over and the derelicts

drool on your drawings. Little children knock your ink over, and your dog

chases the little children and the mothers chase you. But all of that is

actually an adventure and all of that gets into the drawing," he told The

Times in 1984.

There are few straight lines in his black-and-white studies. He found what

he called "the wonderfulness of man" in a grand edifice like downtown's

Biltmore Hotel and the much humbler Casa Garcia, a defunct Montebello eatery

shaped like a wrapped tamale.

Another building that sprang to life in his hands was the Dog and Cat

Hospital, a small, two-story building in Los Angeles with a bas relief of bird

dogs hunting ducks and a stucco pediment topped with a neon Dalmatian. It is

still standing, minus some of the eccentric touches that had charmed Parker

and caused him to lament, "Nowadays you can't tell a dog and cat hospital from

a dentist's office."

"Los Angeles continually makes me smile," the artist wrote. "Even the

freeways are okay. Just don't drive during rush hours. And if you do, it's a

grand time for looking at buildings."

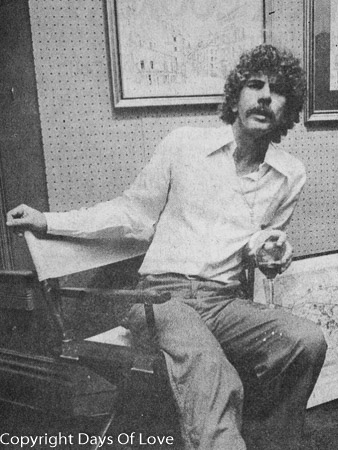

Robert Miles Parker (August 22, 1939 - April 17, 2012)

was a free-spirited artist who sparked an

architectural preservation movement in San Diego and translated the

personalities of Los Angeles and New York into distinctive pen-and-ink

drawings of their buildings.

Robert Miles Parker (August 22, 1939 - April 17, 2012)

was a free-spirited artist who sparked an

architectural preservation movement in San Diego and translated the

personalities of Los Angeles and New York into distinctive pen-and-ink

drawings of their buildings.