Queer Places:

Yale University (Ivy League), 38 Hillhouse Ave, New Haven, CT 06520

29 Beekman Pl, New York, NY 10022

Russell Wheeler

“Mitch” Davenport (1899 – April 19, 1954) was an American publisher

and writer. He was part of the

Literary Ambulance

Drivers during WWI. Russell Wheeler Davenport and Max Foster were

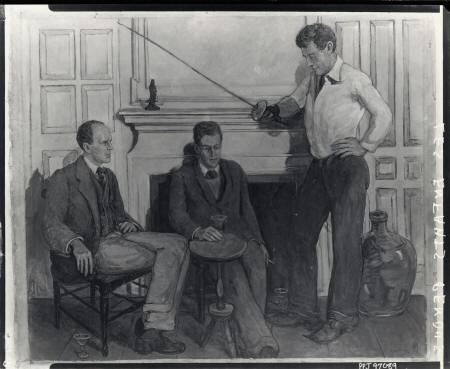

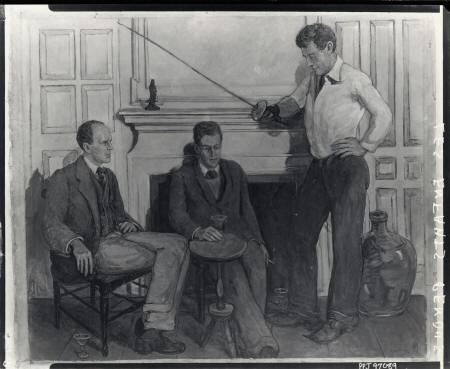

immortalized in Phelps Putnam’s poetry (and in a painting by

Russell Cheney) as “Les Enfants Pendus,”

which the poet translated as “the hung-up children.” The three of them are

depicted in the poem as hanging by their necks from a tree, although they are

not dead. Putnam wasn’t alone in his sexual conflicts. Among his close

friends, at least two, Mitch Davenport and

Farwell Knapp, offer striking

parallels to his own life: both were trapped in unhappy marriages and only

truly content when in the company of men they loved. In Davenport’s case, his

letters and journals reveal homosexual experiences in college, as well as a

lifelong sexual struggle that often left him depressed and bitter. In

addition, a third member of their group,

Charlie Walker (who’d also marry and

have children), was arrested in 1916 on an apparent morals charge, which

usually meant public homosexual activity. People like Putnam and Davenport,

who could never conceive of themselves as homosexual, despite their love for

other men. Homosexuals were fairies, pansies, or “little boys”—a label Cheney

once angrily derided as “filthy” when a friend used it to describe his largely

gay circle of friends. The number of suicides in Putnam’s circle is striking:

Farwell Knapp put a gun to his head;

Parker Lloyd-Smith, boon companion of Mitch Davenport, leaped from the

twenty-third floor of a building. Even

F.O. Matthiessen, the most

grounded of the whole group, plunged from the twelfth floor of a Boston hotel

in 1950, depressed over Cheney’s death and weary of being hounded for both his

homosexuality and his political views. Mitch Davenport professed to be in love

with Laura Barney Harding

and probably would have divorced his wife if Laura had given the nod. But

Mitch’s anguish over the suicide of his friend Parker Lloyd-Smith, with whom

he admitted he’d been “more than intimate,” seems to have given Laura pause.

Russell Wheeler

“Mitch” Davenport (1899 – April 19, 1954) was an American publisher

and writer. He was part of the

Literary Ambulance

Drivers during WWI. Russell Wheeler Davenport and Max Foster were

immortalized in Phelps Putnam’s poetry (and in a painting by

Russell Cheney) as “Les Enfants Pendus,”

which the poet translated as “the hung-up children.” The three of them are

depicted in the poem as hanging by their necks from a tree, although they are

not dead. Putnam wasn’t alone in his sexual conflicts. Among his close

friends, at least two, Mitch Davenport and

Farwell Knapp, offer striking

parallels to his own life: both were trapped in unhappy marriages and only

truly content when in the company of men they loved. In Davenport’s case, his

letters and journals reveal homosexual experiences in college, as well as a

lifelong sexual struggle that often left him depressed and bitter. In

addition, a third member of their group,

Charlie Walker (who’d also marry and

have children), was arrested in 1916 on an apparent morals charge, which

usually meant public homosexual activity. People like Putnam and Davenport,

who could never conceive of themselves as homosexual, despite their love for

other men. Homosexuals were fairies, pansies, or “little boys”—a label Cheney

once angrily derided as “filthy” when a friend used it to describe his largely

gay circle of friends. The number of suicides in Putnam’s circle is striking:

Farwell Knapp put a gun to his head;

Parker Lloyd-Smith, boon companion of Mitch Davenport, leaped from the

twenty-third floor of a building. Even

F.O. Matthiessen, the most

grounded of the whole group, plunged from the twelfth floor of a Boston hotel

in 1950, depressed over Cheney’s death and weary of being hounded for both his

homosexuality and his political views. Mitch Davenport professed to be in love

with Laura Barney Harding

and probably would have divorced his wife if Laura had given the nod. But

Mitch’s anguish over the suicide of his friend Parker Lloyd-Smith, with whom

he admitted he’d been “more than intimate,” seems to have given Laura pause.

Les Enfants Pendus [painting], "Russell Cheney, 1881-1945: A Record of his Work with notes by F. O. Matthiessen," New York: Oxford University Press, 1947.

.jpg)

Yale University, New Haven, CT

Davenport was born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, the son of Russell W.

Davenport, Sr., a vice president of Bethlehem Steel, and Cornelia Whipple

Farnum.

In his journals, he writes of love for women, particularly his first

fiancée, in an idealized way. Since love for women was so sacred, Davenport

wrote, he “suppressed” his “animal desires” for them—which, he then

rationalized, came out “highly unnaturally,” that is, through sex with men. In

college, he had a sexual relationship with his classmate

Robert Chapman "Bob" Bates, later

a professor of French literature at Yale. Bates seems to have wanted the

relationship to continue, writing love sonnets to Davenport. He asked him at

one point, after clearly being rebuffed, “Ah, Mitch—are you still seeking

‘experience’? Are you still looking for material for novels—are you still that

same strange self of yours, forever just not happy?”

He served with the U.S. Army in World War I and received the Croix de

Guerre. He enrolled at Yale University and graduated in 1923, where he was

classmate of Henry Luce and Briton Hadden, who founded Time magazine. While at

Yale he became a member of the secret society Skull and Bones.[1]

In 1929, he married the writer Marcia Davenport (Marcia Davenport’s novel, Of

Lena Geyer, is based on her mother, Alma

Gluck’s longterm lesbian relationship); they divorced in 1944. Marcia and Russell Davenport had a daughter, Cornelia Whipple Davenport, in 1934. He

joined the editorial staff of Fortune magazine in 1930 and became managing

editor in 1937.

At age forty-one, he turned to politics and became a personal and political

advisor to Wendell Willkie. Willkie was the Republican nominee for the 1940

presidential election and lost the election to Franklin D. Roosevelt. After

Willkie's death in 1944, Davenport became a defacto leader of the

internationalist Republicans.

Following World War II, he was on the staff of Life and Time

until 1952. In 1944, Simon and Schuster published one of his works, "My

Country, A Poem of America". His book The Dignity of Man was

published posthumously in 1955.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

Russell Wheeler

“Mitch” Davenport (1899 – April 19, 1954) was an American publisher

and writer. He was part of the

Literary Ambulance

Drivers during WWI. Russell Wheeler Davenport and Max Foster were

immortalized in Phelps Putnam’s poetry (and in a painting by

Russell Cheney) as “Les Enfants Pendus,”

which the poet translated as “the hung-up children.” The three of them are

depicted in the poem as hanging by their necks from a tree, although they are

not dead. Putnam wasn’t alone in his sexual conflicts. Among his close

friends, at least two, Mitch Davenport and

Farwell Knapp, offer striking

parallels to his own life: both were trapped in unhappy marriages and only

truly content when in the company of men they loved. In Davenport’s case, his

letters and journals reveal homosexual experiences in college, as well as a

lifelong sexual struggle that often left him depressed and bitter. In

addition, a third member of their group,

Charlie Walker (who’d also marry and

have children), was arrested in 1916 on an apparent morals charge, which

usually meant public homosexual activity. People like Putnam and Davenport,

who could never conceive of themselves as homosexual, despite their love for

other men. Homosexuals were fairies, pansies, or “little boys”—a label Cheney

once angrily derided as “filthy” when a friend used it to describe his largely

gay circle of friends. The number of suicides in Putnam’s circle is striking:

Farwell Knapp put a gun to his head;

Parker Lloyd-Smith, boon companion of Mitch Davenport, leaped from the

twenty-third floor of a building. Even

F.O. Matthiessen, the most

grounded of the whole group, plunged from the twelfth floor of a Boston hotel

in 1950, depressed over Cheney’s death and weary of being hounded for both his

homosexuality and his political views. Mitch Davenport professed to be in love

with Laura Barney Harding

and probably would have divorced his wife if Laura had given the nod. But

Mitch’s anguish over the suicide of his friend Parker Lloyd-Smith, with whom

he admitted he’d been “more than intimate,” seems to have given Laura pause.

Russell Wheeler

“Mitch” Davenport (1899 – April 19, 1954) was an American publisher

and writer. He was part of the

Literary Ambulance

Drivers during WWI. Russell Wheeler Davenport and Max Foster were

immortalized in Phelps Putnam’s poetry (and in a painting by

Russell Cheney) as “Les Enfants Pendus,”

which the poet translated as “the hung-up children.” The three of them are

depicted in the poem as hanging by their necks from a tree, although they are

not dead. Putnam wasn’t alone in his sexual conflicts. Among his close

friends, at least two, Mitch Davenport and

Farwell Knapp, offer striking

parallels to his own life: both were trapped in unhappy marriages and only

truly content when in the company of men they loved. In Davenport’s case, his

letters and journals reveal homosexual experiences in college, as well as a

lifelong sexual struggle that often left him depressed and bitter. In

addition, a third member of their group,

Charlie Walker (who’d also marry and

have children), was arrested in 1916 on an apparent morals charge, which

usually meant public homosexual activity. People like Putnam and Davenport,

who could never conceive of themselves as homosexual, despite their love for

other men. Homosexuals were fairies, pansies, or “little boys”—a label Cheney

once angrily derided as “filthy” when a friend used it to describe his largely

gay circle of friends. The number of suicides in Putnam’s circle is striking:

Farwell Knapp put a gun to his head;

Parker Lloyd-Smith, boon companion of Mitch Davenport, leaped from the

twenty-third floor of a building. Even

F.O. Matthiessen, the most

grounded of the whole group, plunged from the twelfth floor of a Boston hotel

in 1950, depressed over Cheney’s death and weary of being hounded for both his

homosexuality and his political views. Mitch Davenport professed to be in love

with Laura Barney Harding

and probably would have divorced his wife if Laura had given the nod. But

Mitch’s anguish over the suicide of his friend Parker Lloyd-Smith, with whom

he admitted he’d been “more than intimate,” seems to have given Laura pause.

.jpg)