Queer Places:

Erdmannstraße 6, 10827 Berlin, Germany

Chronicler of Berlin's lesbian club scene of the late 1920s, writer Ruth Margarete Roellig (December 14, 1878 – July 31, 1969) was part of the lively gay counterculture of Germany's Weimar era. Although she survived the rise to power of the Nazis and lived well past the end of World War II, Roellig's most popular work was done during the Weimar period.

Chronicler of Berlin's lesbian club scene of the late 1920s, writer Ruth Margarete Roellig (December 14, 1878 – July 31, 1969) was part of the lively gay counterculture of Germany's Weimar era. Although she survived the rise to power of the Nazis and lived well past the end of World War II, Roellig's most popular work was done during the Weimar period.

Roellig was born in Schwiebus, Germany on December 14, 1878, to a family in the restaurant and hotel business.

Her parents were Anna and Otto Roehlig. She was sent to exclusive schools in Berlin and Saxony, where she studied to become an editor.

After leaving school, Roellig first helped in the family's hotel business,

then in 1911– 1912 took up an apprenticeship with a Berlin publisher, and from

there moved into a post as editor. Like many educated women--even in later eras--she had to support herself with secretarial work before advancing in the publishing industry.

Roellig began her writing career by publishing in literary magazines and newspapers. At the age of 35, she published her first novel, Geflüster im Dunkel (Whispers in the Dark, 1913), about a poet and his muse. Her travels in Finland and Paris provided settings for two other works, Traumfahrt -- Eine Geschichte aus Finnland (Dream Journey: A Story from Finland, 1919) and Lutetia Parisorum (1920). The latter work, a novel, is set amidst Parisian theater and circus life.

After travelling in Finland, Germany and France, Roellig returned to Berlin

in 1927, where she worked for two popular lesbian-feminist journals, Die

Freundin (The Girlfriend), and Garçonne. She immersed herself in Berlin's "world of women." In her Schöneberg district home, where she lived with a much younger woman partner and a pet monkey, she hosted parties for writers and actresses, and pursued interests in spiritualism and the occult.

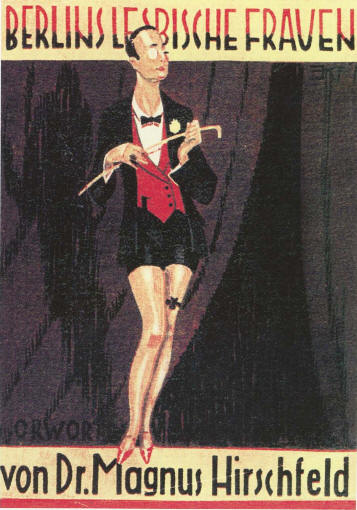

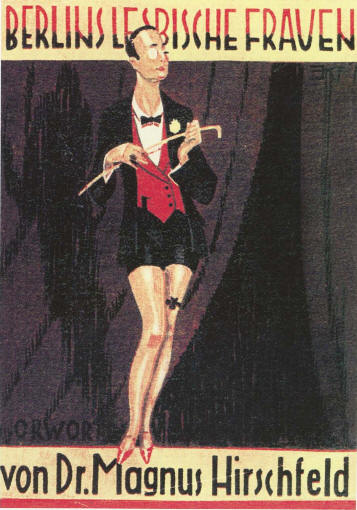

Roellig is best known for her guidebook to Berlin's lesbian clubs, Berlins lesbische Frauen (The Lesbians of Berlin, 1928), which featured a preface by pioneering German sexologist and activist

Magnus Hirschfeld.

After an introduction deploring religious attitudes toward lesbians and decrying discrimination against "priestesses of Sappho," Roellig describes the ambience and offerings of 14 Berlin clubs and dance halls that catered to lesbians. At this time in Germany, lesbians were not subject to criminal prosecution, but they faced ostracism and employment discrimination, and Roellig is keenly aware of such injustices. Indeed, her introduction must be considered a contribution to the literature of the Geman homosexual emancipation movement.

Hirschfeld's preface was featured prominently on the book's cover in order to characterize the book as a work of social significance rather than simply a guidebook for tourists. But perhaps the greatest function of Berlins lesbische Frauen was to alert isolated women to the presence of a larger lesbian community. As a measure of its success in this endeavor, the book underwent several printings.

In "Lesbierinnen und Transvestiten" (Lesbians and Transvestites), her contribution to

Agnes Countess Esterhazy's 1930 collection Das lasterhafte Weib (The Vices of Women), Roellig again attacks prejudices against lesbians and other sexual minorities.

Roellig also published poems, articles, and short stories in outlets such as the lesbian magazine Frauenliebe (Woman's Love, which later became Garçonne) into the early 1930s. Her 1930 short story "Ich Klage an" (I Accuse) deals with a lesbian struggling against authority; a novel, Die Kette im Schoss (The Chain in the Lap), about young Persian women living in Berlin, was published in 1931 and also features lesbian characters.

Roellig's career as a nonconformist writer was sidetracked when the Nazis came to power in 1933. Bowing to the political pressures of the new regime, Roellig joined the Reich Literature Association, membership in which was required for publishing during the Nazi period.

Under the Nazis watchful eyes, Roellig continued to write. Her novels, Der Andere (The Other, 1935), a mystery, and Soldaten, Tod, Tänzerin (Soldiers, Death, Dancer, 1937), a heroine tale set during World War I, complete with anticommunist and anti-Semitic references, include strong women characters who may be read as lesbian in highly coded terms, but they have generally been seen as pandering to romantic myths of the fatherland. The anti-Semitic references were probably necessary in order for Roellig to maintain good standing with the government; she is known to have offered shelter to a Jewish acquaintance on at least one occasion during this period.

Accommodationist strategies appear not to have helped Roellig very much. In 1938 Berlins lesbische Frauen was included on the government's list of "harmful writings" and banned from circulation. (In the 1980s and 1990s, however, it was reissued in German and French editions.)

Although her Berlin home was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1943, Roellig survived the war. After a brief period living in Silesia, she and her partner

Erika resided in Berlin with Roellig's sister in the post-war years.

Roellig lived to be 91. She died on July 31, 1969.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- Author: Pettis, Ruth M.

Entry Title: Roellig, Ruth Margarete

General Editor: Claude J. Summers

Publication Name: glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual,

Transgender, and Queer Culture

Publication Date: 2005

Date Last Updated August 16, 2005

Web Address www.glbtq.com/literature/roellig_rm.html

Publisher glbtq, Inc.

1130 West Adams

Chicago, IL 60607

Today's Date January 19, 2020

Encyclopedia Copyright: © 2002-2006, glbtq, Inc.

Entry Copyright © 2005, glbtq, inc.

- Robert Aldrich and Garry Wotherspoon. Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian

History Vol.1: From Antiquity to the Mid-Twentieth Century: From Antiquity

to the Mid-twentieth Century Vol 1 (p.376). Taylor and Francis. Edizione

del Kindle.

Chronicler of Berlin's lesbian club scene of the late 1920s, writer Ruth Margarete Roellig (December 14, 1878 – July 31, 1969) was part of the lively gay counterculture of Germany's Weimar era. Although she survived the rise to power of the Nazis and lived well past the end of World War II, Roellig's most popular work was done during the Weimar period.

Chronicler of Berlin's lesbian club scene of the late 1920s, writer Ruth Margarete Roellig (December 14, 1878 – July 31, 1969) was part of the lively gay counterculture of Germany's Weimar era. Although she survived the rise to power of the Nazis and lived well past the end of World War II, Roellig's most popular work was done during the Weimar period.