Queer Places:

464 N Myrtle Ave, Monrovia, CA 91016

Helicon

Hall, Englewood, NJ 07631

Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

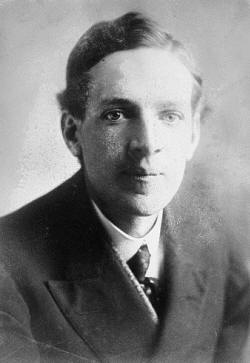

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in several genres. Sinclair's work was well known and popular in the first half of the 20th century, and he won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1943.

In 1906, Sinclair acquired particular fame for his classic muck-raking novel The Jungle, which exposed labor and sanitary conditions in the U.S. meatpacking industry, causing a public uproar that contributed in part to the passage a few months later of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act.[1] In 1919, he published The Brass Check, a muck-raking exposé of American journalism that publicized the issue of yellow journalism and the limitations of the "free press" in the United States. Four years after publication of The Brass Check, the first code of ethics for journalists was created.[2] Time magazine called him "a man with every gift except humor and silence".[3] He is also well remembered for the line: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."[4] He used this line in speeches and the book about his campaign for governor as a way to explain why the editors and publishers of the major newspapers in California would not treat seriously his proposals for old age pensions and other progressive reforms.[4]

Many of his novels can be read as historical works. Writing during the Progressive Era, Sinclair describes the world of industrialized America from both the working man's and the industrialist's points of view. Novels such as King Coal (1917), The Coal War (published posthumously), Oil! (1927), and The Flivver King (1937) describe the working conditions of the coal, oil, and auto industries at the time.

The Flivver King describes the rise of Henry Ford, his "wage reform" and his company's Sociological Department, to his decline into antisemitism as publisher of The Dearborn Independent. King Coal confronts John D. Rockefeller Jr., and his role in the 1914 Ludlow Massacre in the coal fields of Colorado.

Sinclair was an outspoken socialist and ran unsuccessfully for Congress as a nominee from the Socialist Party. He was also the Democratic Party candidate for Governor of California during the Great Depression, running under the banner of the End Poverty in California campaign, but was defeated in the 1934 elections.

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in several genres. Sinclair's work was well known and popular in the first half of the 20th century, and he won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1943.

In 1906, Sinclair acquired particular fame for his classic muck-raking novel The Jungle, which exposed labor and sanitary conditions in the U.S. meatpacking industry, causing a public uproar that contributed in part to the passage a few months later of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act.[1] In 1919, he published The Brass Check, a muck-raking exposé of American journalism that publicized the issue of yellow journalism and the limitations of the "free press" in the United States. Four years after publication of The Brass Check, the first code of ethics for journalists was created.[2] Time magazine called him "a man with every gift except humor and silence".[3] He is also well remembered for the line: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."[4] He used this line in speeches and the book about his campaign for governor as a way to explain why the editors and publishers of the major newspapers in California would not treat seriously his proposals for old age pensions and other progressive reforms.[4]

Many of his novels can be read as historical works. Writing during the Progressive Era, Sinclair describes the world of industrialized America from both the working man's and the industrialist's points of view. Novels such as King Coal (1917), The Coal War (published posthumously), Oil! (1927), and The Flivver King (1937) describe the working conditions of the coal, oil, and auto industries at the time.

The Flivver King describes the rise of Henry Ford, his "wage reform" and his company's Sociological Department, to his decline into antisemitism as publisher of The Dearborn Independent. King Coal confronts John D. Rockefeller Jr., and his role in the 1914 Ludlow Massacre in the coal fields of Colorado.

Sinclair was an outspoken socialist and ran unsuccessfully for Congress as a nominee from the Socialist Party. He was also the Democratic Party candidate for Governor of California during the Great Depression, running under the banner of the End Poverty in California campaign, but was defeated in the 1934 elections.

In April 1900, Sinclair went to Lake Massawippi in Quebec to work on a novel. He had a small cabin rented for three months and then he moved to a farmhouse.[6] Here, he was reintroduced to his future first wife, Meta Fuller, a childhood friend whose family was one of the First Families of Virginia. She was three years younger than him and had aspirations of being more than a housewife. Sinclair gave her direction as to what to read and learn.[6] Each had warned the other about themselves and would later bring that up in arguments. They married on October 18, 1900.[6] They used abstinence as their main form of birth control, but Meta became pregnant shortly after they married; she unsuccessfully attempted to terminate the pregnancy via abortion multiple times.[6] The child, David, was born on December 1, 1901.[36][a] Meta and her family tried to get Sinclair to give up writing and get "a job that would support his family."[6] Around 1911, Meta left Sinclair for the poet Harry Kemp,[38] later known as the "Dunes Poet" of Provincetown, Massachusetts. In 1913, Sinclair married Mary Craig Kimbrough (1883–1961), a woman from an elite Greenwood, Mississippi, family. She had written articles and a book on Winnie Davis, the daughter of Confederate States of America President Jefferson Davis. He met her when she attended one of his lectures about The Jungle.[39] In the 1920s, the Sinclair couple moved to California. They were married until her death in 1961. Sinclair married again, to Mary Elizabeth Willis (1882–1967).[40] Sinclair was opposed to sex outside of marriage and he viewed marital relations as necessary only for procreation.[41] He told his first wife Meta that only the birth of a child gave marriage "dignity and meaning".[42] Despite his beliefs, he had an adulterous affair with Anna Noyes during his marriage to Meta. He wrote a novel about the affair called Love's Progress, a sequel to Love's Pilgrimage. It was never published.[43] His wife next had an affair with John Armistead Collier, a theology student from Memphis; they had a son together named Ben.[44] In his novel, Mammonart, he suggested that Christianity was a religion that favored the rich and promoted a drop of standards. He was against it.[45] Late in life Sinclair, with his third wife Mary Willis, moved to Buckeye, Arizona. They returned east to Bound Brook, New Jersey. Sinclair died there in a nursing home on November 25, 1968, a year after his wife.[38] He is buried in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C., next to Willis.

My published books: