Queer Places:

Columbia University (Ivy League), 116th St and Broadway, New York, NY 10027

Pipe Creek Farm, Saw Mill Rd E & Murkle Rd, Westminster, MD 21158

Whittaker Chambers (April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was a writer and editor and one-time member of the American Communist Party.

He was not only forced into the world spotlight at a time of great

national division, but he also became both a cause and a symbol of that division.

Whittaker Chambers (April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was a writer and editor and one-time member of the American Communist Party.

He was not only forced into the world spotlight at a time of great

national division, but he also became both a cause and a symbol of that division.

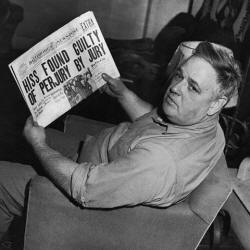

Summoned to appear before the much-feared House Un-American Activities Committee in 1948, Chambers accused Alger Hiss, a personable and successful executive who had previously worked at the U. S. State Department, of being a communist spy. Hiss vehemently denied the charge, though he was later convicted of perjury and served over three years in prison. Scholars still debate the question of who lied and who told the truth in the Hiss-Chambers case. Rumors of Chambers' homosexuality and of an attraction or relationship between Chambers and Hiss persisted throughout the case and into the present. The aura of homosexuality in this case helped perpetuate the connection in the public mind between homosexuality and treason that was a hallmark of McCarthyism.

Whittaker Chambers was born Jay Vivian Chambers on April 1, 1901 into an aristocratic New York family. His father, also named Jay Vivian, was a bisexual who kept a second residence apart from his wife and children so that he could pursue gay relationships. Young Jay was an alienated and lonely child who did not do well in school. He did, however, have an intellectual curiosity that impelled him to study languages and history on his own. In 1919, after graduation from high school, Chambers left home. Seeking experience and adventure, he spent several months working on railroad crews and in shipyards. He returned to enter Columbia University, but in 1923 left to spend time in Europe.

Chambers' travels introduced him to the lives of working class people and immigrants and to the ideas of communism. He began to read the writings of Soviet Russian leader Vladimir Ilich Lenin and soon became a communist. He worked as a writer and editor for the party newspaper Daily Worker and, later, for the Stalinist organ The New Masses. In 1932, Chambers was chosen by party leadership to be a part of an underground communist organization devoted to passing U. S. government secrets to the Soviet Union. For the next six years, he worked for the group, chiefly as a messenger, delivering information from one agent to another. Around 1938, he became disillusioned with the politics and divisions within the party and fearful about his role in it. In 1931 he had married fellow party member Esther Shemitz. They had two children, and Chambers began to fear for his family. He and Esther defected from the party and went into hiding for almost a year. In 1939, Chambers got a job as a book reviewer at Time magazine. As his past in the party underground became more distant, he took an increasingly public role in the journal and began to work his way up to editor.

Chambers was a senior editor at Time in 1948 when anti-communist fervor began to sweep the United States. He was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, confessed his own past connections to the party, and shocked the nation by naming a popular former State Department employee, Alger Hiss, as a fellow spy. Hiss not only denied being a member of the communist underground, but also denied being close friends with Chambers. During the hearings and Hiss's later perjury trial, his lawyers seemed to be planning to use Chambers' gay activities to discredit him. To forestall this, Chambers "confessed" to homosexual tendencies, but insisted that he had overcome them. The Hiss defense never brought up Chambers' gayness, perhaps fearing that the accusation might backfire on Hiss himself.

After Hiss was convicted, not of treason, but of lying to the grand jury, Chambers found that his own life would never be the same. The details of his past and the distasteful public exposure of the hearings had made his colleagues at Time reluctant to have him back. He served as a government witness in several other anti-communist hearings and spent several years writing his memoir of the affair, which became a best seller on its publication in 1952. In 1955 he took a job with arch-conservatives William F. Buckley and Willi Schlamm as senior editor on the right-wing magazine National Review. On July 9, 1961, six years after Alger Hiss was released from prison, Chambers died of a heart attack at his Maryland farm.

The significance of the Chambers-Hiss case for glbtq history lies in the fact that it helped usher in McCarthyism, a dark period in American history in which gay men became the chief scapegoats of the Cold War. It was a time characterized by police harassment, witch hunts, suspicions of disloyalty, and dismissals from jobs, especially in the public sector. In 1999, Peter K. Leisure, a federal judge in New York, ordered the Hiss case grand jury testimony unsealed, shedding light on events that had been kept secret for over fifty years. The ambiguities of the Chambers- Hiss case contributed much to future rulings and laws that provided more openness and less secrecy in governmental actions.

My published books: