Queer Places:

Schloss Eerde, Kasteellaan 1, 7731 PJ Ommen, Netherlands

Beverweerd Castle, Beverweertseweg 60, 3985 RE Werkhoven, Netherlands

William Hilsley, née William Josef Hildesheimer (born December 15, 1911 in London; d. January 12, 2003 at Schloss Beverweerd in Werkhoven, Utrecht, Netherlands) was german-British composer, musician and music educator. He grew up in Germany, then emigrated to the Netherlands, where he continued to live after his internment in Germany. He is best known for his works composed and performed in the internment camps.

William Hilsley, née William Josef Hildesheimer (born December 15, 1911 in London; d. January 12, 2003 at Schloss Beverweerd in Werkhoven, Utrecht, Netherlands) was german-British composer, musician and music educator. He grew up in Germany, then emigrated to the Netherlands, where he continued to live after his internment in Germany. He is best known for his works composed and performed in the internment camps.

William (Billy) Hilsley, the name under which he is remembered as a musician and composer, was born William Josef Hildesheimer in London in 1911.[1] His Jewish parents, who divorced shortly after his birth, were Adolf Hildesheimer (born 1860) and Frida

Heimann(1875–1952). From the marriage comes at least another son Kurt, born in 1901.[2]

In 1914 Frida Hildesheimer left England with her sons Kurt and William and

moved to Berlin. Here William later attended the Hohenzollerngymnasium, where

he also enjoyed his "first and life-changing encounter with the Quakers".[3] Another "life-changing" encounter also took place during these years.

Wolfgang Frommel got to know 13-year-old Billy and his mother Frida Hildesheimer through

the actor couple Paul and Lotte Bildt in Berlin.[4] On February 17, 1924, Frommel wrote in a letter to his parents: "So this year I am almost daily with little Billi Hildesheimer, work with him in French and experience the most outrageous miracles humanly."[5] William Hilsley lived with his mother in the Bavarian Quarter of Berlin, where many prominent Jews lived. "The mother had studied with a disciple of Liszt; People from the

Stefan George circle or the Minister of Culture Becker went in and out of the house."[6] "Frida loved her son and his educator Wolfgang Frommel with equal ferocity and devotion."[7]

Friedrich W. Buri, who lived with Frida Hildesheimer for some time in 1937, writes that she was a sought-after English teacher: "She gave private lessons and courses for small groups of Jewish people who wanted to leave Germany as soon as possible to emigrate to a country where they would have to speak English. Frida's crash courses were famous in the west of Berlin, they were crowded with more students than she could accommodate."[8]

From then on, the lives of Wolfgang Frommel and William Hilsley were closely linked, so close that their relationship is often compared to those within the George circle: "In addition, Gothein and F. gathered a

circle around themself, which resembled George's in its approach (with Achim and Hasso Akermann, Cyril Hildesheimer and others)."[9]

Hilsley first left Berlin[10] and attended the Schule Schloss Salem,[11] where he graduated from high school in 1930. He then returned to Berlin and studied at the State Academy for Church and School Music. By now at the latest, Hilsley was firmly integrated into the circle around Wolfgang Frommel, who lived with Frida Hildesheimer in 1934[12] and was one of Frommel's constant companions.[13] The friendship with Adolf Wongtschowski ('Buri')[14]

must also have developed during this time, because "in addition to Billy

Hildesheimer, whom he had Frommel as a tutor in the 1920s, Buri became the most attentive Jewish pupil of this time".[15]

The 91-year-old music teacher Billy Hilsley[16], still "revered by his former students" in 2002, left Germany in 1935 and went to the Quaker School Eerde as a music teacher. How this came about can be seen from the estate of Hildegard Feidel-Mertz in the German Exile Archive. There is the transcript of a tape interview with William Hilsley on March 30, 1981. Among other things,

she tells how he was placed in Eerde by Eva Warburg, with whose sister Ingrid he had attended school in Salem. Eva and Ingrid's younger sister Noni

were students in Eerde. Her cousin, Max A. Warburg, was a teacher there.[17]

On January 28, 1935, Hilsley arrived in Eerde, and what Katharina Petersen, the headmistress at the time, could offer him was not stunning: No salary, but pocket money, a room of his own, food and laundry.

"We have a piano and a grand piano. How the school will survive financially is quite uncertain, but if you have the courage to join us, please do."[18] The young refugee from Nazi Germany stayed.

In 1962, Katharina Petersen still remembers Billy Hilsley with a great deal of enthusiasm.

Katharina Petersen resigned from the school in 1938 and returned to Germany. Her successor as headmaster was Kurt Neuse, but he only became provisional, and this provisional status was never changed.

Billy Hilsley still had two years until fears of war susperseded fears of moral contamination.[22] He was still able to develop his gift of "not letting music become a game, but teaching in such a way that serious and thorough work was done, both for domestic use and for concerts to which guests were invited, as well as for the small chamber music to which amateur musicians, piano and violin players from the surrounding area magnetically attracted to him came. The most beautiful thing was that in addition to the aesthetics of his music-making and teaching, healing powers were also released. He found out what was in the boys and girls, stimulated, restored self-confidence where they were destroyed."[23]

No less impressed and impressive, Buri describes the work of his friend Hilsley ("Cyril"):

"Cyril seemed to me like the uncrowned king of the castle. Although he did not live much more spacious in his basement dungeon than I did in the attic, all the threads of the Parzen came together in his hermitage. Here he planned and designed the serious hours of fire and cheerful festivals, which formed not only for the adults and students the fixed highlights, according to which the fleeing time was divided; also for visitors from outside, the face of the castle community was determined by Cyril's activities. [24]"

After the German occupation of the Netherlands in 1940, Hilsley, Frommel and Buri tried to flee from Scheveningen to England. They rejected the plan and went into hiding in Amsterdam, where Frommel expressed suicidal thoughts. After the friends had talked him out of it, they went back to Eerde. It was here that British citizen William Hilsley was arrested on July 25, 1940.

Hilsley was first interned in the Dutch camp Schoorl before he was transferred together with other British non-combatants to a civilian internment camp in the German Reich.[26] This camp was located in Tost in Upper Silesia,[27] where

he remained until the spring of 1942. At the same time as him, the writer P. G. Wodehouse was interned there. Hilsley, who traced his musical influence back to his school days in Salem,[29] began his "career" as a camp musician with the performance of classical music. After a fierce argument with other prisoners, he then tried other things: pantomimes, fairy tale performances with music and costumes, cabaret, musical. He saw his task in bringing the other internees into a cheerful mood through music. And he began to compose.[29]

His status as a civilian internee granted him a certain degree of protection and greater freedom of movement. The camp was monitored by aid organizations from neutral countries and the prisoners were encouraged to develop leisure activities including a variety of educational, theatrical, and musical programs.[30] Hilsley made good use of the possibilities and played the piano regularly. In four different camps, he built a thriving music scene with other internees.[29] Since Hilsley was adept at various aspects of musical production and staging, he immediatly became involved in preparing concerts an staged cabaret shows.[30]

In the Tost camp, relatively humane conditions seem to have prevailed, which Hilsley attributes primarily to the camp commander[31], Lieutenant Colonel Buchert,[32], "a man with a good German mentality, which somehow still existed. He was a real gentleman."[29] The next episode narrated by Hilsley reads: "In the Tost camp we had no instrument at first. The lieutenant colonel suggested buying or renting instruments in the nearby town of Gliwice. How it was paid, I don't know. We had to give up our money and instead got storage money, a ten a week. Perhaps it was this confiscated money that paid for the wing. The Germans were happy that we wanted to give musical performances. Above all, they wanted the camp's affairs to be calm and smooth. There should be no revolt. So the lieutenant colonel took me in his car to Gliwice. He also had to do some shopping for himself, so at a certain point I was sitting alone in his car. I could have gone away. I didn't have a passport, but still, I spoke fluently German. I would have come a long way. Nevertheless, I stayed in the car. The lieutenant colonel was such a decent person, a friend almost, I was beholden to him."[29]

The further progress of this story: "The first wing that came was not good, it was tuned to a height that was useless for us. I sent him back and we got another one. That was the central instrument for our performances. We had a good cellist who had brought his instrument to the camp, an oboist, singer, actor, dancer. We received sheet music from the YMCA, which inspected all the internment camps."[29] The work of the YMCA was of immense importance to Hilsley and his fellow prisoners.

It is also thanks to the YMCA and its collaborator Henry Söderberg[33] that Hilsley's musical commitment was able to develop in the camp and that his music became known "beyond the barbed wire" and was preserved for posterity.

In mid-1942, Hilsley was transferred from Tost to Kreuzburg (Upper Silesia) as an internee of Jewish faith. "In June 1942 the time had come. All Jews and half-Jews had to go to the Kreuzburg camp, thirty kilometers north of Auschwitz. Coincidentally, all pianists were Jews, and for Tost this meant the end of musical life. In Kreuzburg we were busy with Ghost Train, a big production for which I had composed the piano music, when one day our friends from Tost stood outside the barbed wire and asked if they could join us in the camp. They were all non-Jews, but they wanted to be with us. As a result, Kreuzburg was immediately no longer a Jewish camp. We also listed Ghost Train in another camp, Lamsdorf, a camp for British military prisoners. We had been brought there by the camp management. After the performance, we went back to our own camp."[34]

In gratitude for the non-Jewish fellow prisoners who had voluntarily come to

Kreuzburg and thus offered him greater protection as Jews, and as a Christmas

present, Hilsley composed a piece for a male choir without instrumental accompaniment. For Patrick Henry, this piece is a jewel that is completely different from any kind of music composed during the war in a German camp. It illustrates Hilsley's exquisite musical rhetoric that cannot be attributed to a particular time or national, ethnic or religious style.[30] But the most unlikely event for the time was still pending, a radio broadcast, recorded by Swedish Radio for its internationally broadcast program 'From behind Barbed Wire', which documented life in prisoner of war and civilian internment camps by means of recorded musical performances. For a broadcast from Kreuzburg in July 1944, William Hilsley and fellow inmate Geoffrey Lewis Navada performed an African-American spiritual: 'Go down, Moses, way down in Egypt's land. Tell old Pharaoh to let my people go!'[36] Hilsley himself's memory accentuates this somewhat differently: "The representative of the YMCA had taken the score of my fantasy for oboe with him to Sweden. One day I got a newspaper snippet with an announcement of a radio show of my imagination. I handed over the excerpt to the camp commander at the time. That wasn't Buchert, he was already gone. At first he was against it, saying that I couldn't hear it, but later I was called to the officers' department. 'Number 180, come here' it sounded. We had just found Radio Stockholm when the power went out shortly before the transmission. Airstrike. It usually takes a long time. Half a minute later, the lights blinked again. My oboe fantasy sounded from the speakers. A nice performance, but played a bit too slowly."[29]

After the evacuation of the Kreuzburg camp on 19 January 1945 and a dangerous train journey through Germany, which had been destroyed by the war and continued to be subject to air raids, Hilsey and his comrades reached the internment camp in Spittal an der Drauon 29 January 1945. In a letter dated February 5, 1945 to his Swedish acquaintance Noni Warburg, he jokes about this transfer from Kreuzburg to Spittal: "Yes Noni, now your thoughts have to look for me in another part of Europe. 'Be an internee and see the world!'"[37]

Henry Söderberg, who had come to the Spittal camp in the meantime and also witnessed its liberation by the 8th British Army, met Hilsley there again.

Hilsley's break with the past few years is marked by his change of language. From 4 May, all other diary entries were made in English until the arrival in Scotland and the boarding of the night train from Glasgow to London on 11 June 1945.[40] He later summed up his time in the Tost and Kreuzburg camps: "Some called our camp a paradise. Compared to a concentration camp, this may seem like it. We had cigarettes from the Red Cross packages and good coffee with which we bribed the guards. Sometimes we were drunk by the homemade plum brandy, an idea of the older internees who had gained more experience in the First World War. And we had instruments, we had materials to build a theater stage. But we were held captive behind barbed wire. There were those who committed suicide. The food was just enough not to die, and for big eaters it was really way too little."[29]

After the war he returned to the Netherlands. He changed his name to

Hilsley because it seemed more appropriate for international tours. Hilsley

traveled as a pianist with the ballet of Kurt Jooss for two years through

Europe and North America and then returned to the Netherlands. During this

time, there was also an encounter with the old friends from the circle around

Wolfgang Frommel, as Friedrich W. Buri reports (who continues to call him

"Cyril"): "The journey with the ballet Jooss through German cities should soon

lead him to dance performances in Amsterdam. In Germany Cyril accompanied the

ballets in English uniform, in Holland, on the other hand, and later also on

the tour through America, he sat in a tailcoat at the grand piano. So we saw

him again: the whole Amsterdam group of friends moved across Holland from

performance to performance. Especially the harrowing ballet 'The Green Table'

we did not leave out once, whereby we never tired of rewarding the two

accompanying pianists with long, loud applause in the house, which was always

full.[41]" Hilsley taught again from 1947 at the school in Eerde and from

1959 at the International School Beverweerd, one of the two successor

institutions of the Quaker School Eerde. After the closure of the school in

1997, he remained the last inhabitant of Beverweerd Castle and continued to

live in the tower room he had moved into in 1959. He called it: "An ideal

living space for a musician." He owned a Steinway grand piano, which he could

buy from the 10,000 marks in compensation he had received after the Second

World War as compensation for 5 years of camp.[29] Hilsley conducted the

Dutch premiere of Benjamin Britten's Let's Make an Opera, and his most

important work, the cantata Seasons, which he composed at the request of Henry

Söderberg, who had visited him as a member of the Swedish YMCA (Young Men's

Christian Association) at the time in the internment camps and supported in

his artistic activity, for the fiftieth anniversary of the YMCA Singers'

Association in 1992. In the text, written by Hilsley's friend Ian Gulliford,

winter stands for captivity in war, spring for liberation, summer for the

fullness of life and love, and autumn for devotion to God. [42] Hilsley and

Söderberg met again for the first time in 45 years at this festival. For both

of them, a never broken circle of friendship was formed.

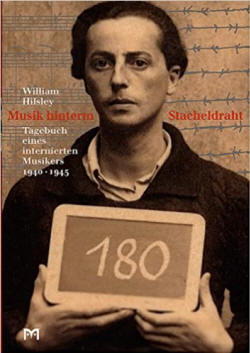

Hilsley had recorded life in the camps in a diary, which was first published in 1988 under the title When joy and pain, Reminiscences. It was an edited extended

version by later memories, the so-called "Trevignano version". When Hilsley searched for this in his documents in order to prepare a new edition of the diaries, "the yellowed sheets of the original version also came to light, which were difficult to read, but gave the impression of authenticity through their telegram style, immediacy and patina.[..] The German musicologist Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Osthoff advised us to publish the original diary version, which was single of all later ingredients, and we followed this advice."[44] Hilsley himself described the difference between the two publications in 1998 as follows: "I wrote down a revised version in Trevignano in 1987. If one compares the two versions, it immediately becomes clear that nothing was written in the original version that could have brought the prisoner into great difficulties when discovered. So I avoided the description of the screaming tone on arrival at the Schnoorl camp, the sneering removal of passports, the humiliating 'you' in the salutation, the orders: open suitcases, keep your mouth shut, here there is order; Pocket knives, pen holders, pointed objects, striking weapons, alcohol, onions strictly prohibited. It also fit into the plan of humiliation that all internees were not allowed to wear their own clothes when they were transported to Germany: with the uniform clothing, the herd could be better kept together."[45] In 1999 the diary was published in a German and a Dutch edition, together with a CD with historical recordings of Hilsley's compositions written during the war.

When he was still very old, he appeared in public events. He took part in a discussion concert in Berlin on 12 October 2000.[46] "On Sunday morning [June 17, 2001], William Hilsley (Billy Hildesheimer), ninety-year-old Jewish music teacher from the circle around Wolfgang Frommel and the magazine CASTRUM PELLEGRINI (Amsterdam), told of his life and especially of his time in German internment camps from 1940 to 1945."[47] And in May 2003, at the age of ninety-one, he attended the fourth meeting of the "Eerde Very Old Pupils (EVOPA)". [48] William Hilsley died on 12 January 2003 at Beverweerd Castle.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

William Hilsley, née William Josef Hildesheimer (born December 15, 1911 in London; d. January 12, 2003 at Schloss Beverweerd in Werkhoven, Utrecht, Netherlands) was german-British composer, musician and music educator. He grew up in Germany, then emigrated to the Netherlands, where he continued to live after his internment in Germany. He is best known for his works composed and performed in the internment camps.

William Hilsley, née William Josef Hildesheimer (born December 15, 1911 in London; d. January 12, 2003 at Schloss Beverweerd in Werkhoven, Utrecht, Netherlands) was german-British composer, musician and music educator. He grew up in Germany, then emigrated to the Netherlands, where he continued to live after his internment in Germany. He is best known for his works composed and performed in the internment camps.