Partner Anthony Towne

Queer Places:

42 Day Ave, Northampton, MA 01060

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

342 E 100th St, New York, NY 10029

Eschaton, 314 SE Rd, New Shoreham, RI 02807

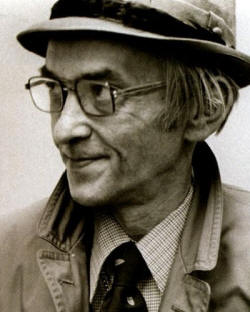

Frank William

Stringfellow (April 26, 1928 - March 2, 1985) was a prominent Christian theologian and advocate for social justice and world peace.

Frank William

Stringfellow (April 26, 1928 - March 2, 1985) was a prominent Christian theologian and advocate for social justice and world peace.

Frank William Stringfellow was born on April 26, 1928 in Thornton, Rhode Island. His father, Frank Stringfellow, was a hosiery knitter. His mother was Margaret Abbott. The family moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, where the father was often unemployed during the Great Depression. Stringfellow was an average student who participated in the debate club in high school. He spent much of his teenage years around the Episcopal parish his family attended. He described himself at the time as “religiously precocious, I read much about religion, and pursued long and sometimes esoteric conversations with the clergy.” He kindled an ardent interest in the Bible and Christian faith. A rector urged him to consider becoming a priest. After some thought Stringfellow declined that vocational path—he said at age 14—sensing that the institutional connections and constraints of that work were not for him. He was not really aware that his family was poor until he talked with his parents about college and learned they could provide no financial assistance. So he took on three part-time jobs during his senior year and found scholarships. He graduated from high school in 1945 and enrolled at Bates College in Lewiston, Maine.

Stringfellow flourished as a university student. He majored in politics and economics, but his passions were politics and religion. He traveled internationally for the first time in July 1947, attending the Second World Conference of Christian Youth in Oslo, Norway. There he heard Martin Niemoller and Reinhold Niebuhr, among other prominent post-World War II Christian leaders. He met other activist students from across Europe and the U.S., relationships which Stringfellow cultivated and expanded over the next decade. Upon his return from Norway, he led his first foray into social activism—by organizing a 1948 sit-in at a local Maine restaurant that refused to serve African-Americans. He was elected president of the student government at Bates and graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1949.

Stringfellow was then awarded a Rotary International Fellowship to study political theory at the London School of Economics. He spent much of 1950 traveling Europe engaging in Student Christian Movement activities. He spoke or led Bible study at several conferences and engaged in discussions of the Bible, theology, Christian vocation, and global politics. Upon his return to the U.S. he was drafted into the U.S. Army during the Korean conflict and served with the Second Armored Division in Germany in 1951-52. He did not enjoy his two years of military service but fulfilled his duties.

Following his military discharge, Stringfellow studied one semester at the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Mass. Given his lifelong passion for politics he set his path toward the study of law, not for a political career but in order to carry out a ministry that embodied his values and principles. He noted that his interest was in a vocation and not a career. He enrolled in Harvard Law School in the fall of 1953 and graduated in 1956.

Upon graduation he joined the ministry team of the East Harlem Protestant Parish as a legal counsel, serving as a lawyer to poor African-American and Latino persons. He lived in a squalid and vermin-infested tenement on East 100th Street. His intention was to get a sense of the workings of the American justice system by observing whether the poor and marginalized could get equal treatment before the law. It took him three tries to pass the bar exam. However, he poured himself into being a legal advocate for the poor and understood years later that his understanding of race and social justice in the U.S. was forged by this experience of living and working side-by-side with the poor and marginalized. On the other hand, he found himself at odds with the leadership of the East Harlem Protestant Parish. He considered them not Biblically-grounded, elitist and clergy-centric; laity were not invited into decision-making. In just over a year he resigned from his position with the Parish, but continued to live there and practice law for several more years. He wrote about this experience in what was the first of many books he would pen over his lifetime, My People Is the Enemy (1962).

Even as he practiced law on the streets of Harlem, he continued to interact with prominent theologians and political theorists around the world. An important influence was Swiss Reformed theologian Karl Barth with whom Stringfellow spoke on a panel at a 1962 symposium at the University of Chicago. Barth’s premise that Christian faith is only vital as it is lived out in the political and social spheres resonated with Stringfellow. During his earlier travel to Europe, he became familiar with French theologian and social historian Jacques Ellul. Ellul and Stringfellow developed a strong personal connection and corresponded with each other regularly, informing each other’s theory and practice for the rest of their lives.

Stringfellow was invited to speak at a ground-breaking National Conference on Religion and Race in Chicago on January 24, 1963. This broad ecumenical gathering of 1,000 delegates included major theologians and leaders of religious bodies from around the world. In his speech, Stringfellow was sharply critical of this assembly as being “too little, too late and too lily white.” Stringfellow sought to expose the fallacy of liberal, northern whites who saw themselves as allies of African-Americans and Southerners as “racists.” Stringfellow understood that racism was a systemic evil that touched everyone. Stringfellow was an ally of Martin Luther King, Jr. and his campaign of nonviolent resistance. Stringfellow often served as legal counsel for persons who had been arrested in demonstrations of nonviolent resistance. But Stringfellow was critical of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society as being paternalistic, assuaging liberal white guilt and not addressing the roots causes of poverty and racism.

For Stringfellow the Bible, theology and social action were deeply interwoven. His theological touchstone was the pervasiveness of “principalities and powers,” forces and idols in the world that serve death. Stringfellow went beyond the knee-jerk liberal supposition of worldly, evil forces that engender war and economic injustice. Stringfellow’s principalities and powers encompassed any corporation, government, political movement, religious or social institution that impinged upon human freedom and fulfillment. The fact that his critiques included religious institutions, even the mainline Protestant denominations in which he moved and worked, made him unpopular in some circles. His theological framework is probably most fully expounded in An Ethic for Christians and Other Aliens in a Strange Land (1973). Stringfellow was unflinchingly in his belief that one could find “truth” in the politics of the Bible. Only when one acknowledges the power of death, can a Christian live fully and freely in love. He embraced resurrection as the overcoming of death’s power.

Stringfellow spoke and acted boldly on the public stage, but his private life was in the shadows. As historians have uncovered the realities of sexual practices in Europe and the U.S. in the 1950s, we can now surmise that Stringfellow moved in circles in which he would have been in contact with same-gender-loving men. His service in the U.S. military in Europe and his extensive travel and meetings with well-educated students in major European and U.S. cities over these years undoubtedly would have led him to circles of homosexual men. Any of Stringfellow’s writings about his personal experiences during these years is cryptic. He wrote an article, “Loneliness, Dread and Holiness,” published in Christian Century on October 10, 1962. There he spoke of the plight of human loneliness and boredom which some persons choose to ameliorate through “lust” and “erotic infatuation.” He described the act of searching for a partner as “transient” and “compulsive.” He stated that ultimately “no one may really find his own identity in another, least of all in the body of another.” Instead he affirmed that Christ alone can fill the vacuum of the human heart. We can speculate that Stringfellow was grappling with the inner conflicts he had experienced between his sexual feelings and practices and his faith.

Meeting Anthony Towne was a life-altering experience for Stringfellow. They first met late in 1962 at an elaborate Manhattan party honoring the General Secretary of the World Council of Churches. Stringfellow was a guest and Towne was a bartender at the party. Both were heavy drinkers and convivial spirits so they made a connection there (no details revealed). A few months later, in early 1963, Towne was being evicted from his apartment and asked for Stringfellow’s legal representation. In one scenario that circulated, Stringfellow neglected to follow through on the case and Towne was stranded on the day of his eviction. Stringfellow wrote another account in which Towne first showed up at his office on the day the eviction was being carried out. Stringfellow helped Towne retrieve some personal belongings and offered him temporary shelter at his apartment. They lived together the rest of their lives. Later Stringfellow wrote that their relationship was “friendship and later community.”

Stringfellow’s legal activities did include advocacy and representation for homosexuals facing legal persecution. He served as legal counsel for the George Henry Foundation. This would have put him in contact with Episcopal clergy—some of whom were closeted homosexuals—who provided support for the Foundation. Stringfellow was invited by Canon Clinton Jones to speak at Christ Church Cathedral in Hartford in 1965. His address, “The Humanity of Sex,” primarily addressed legal issues regarding homosexuality. He made brief mention of the theology and ethics of sexuality, but mostly focused on the legal problems faced by homosexuals as outcasts and marginalized persons in society. He believed his position to be undergirded by Christ’s compassion for the outcast as well as the constitutional right for persons to have equal treatment under the law. He alluded to connections between injustice faced by homosexuals and the racial crisis of the time.

Stringfellow also addressed the Mattachine Society in New York City in 1965. This presentation provides glimpses of his ambivalence about sexuality and homosexuality, particularly in this paragraph: The homosexual’s rejection of the self is responsible, I would venture, at least as much as any other factor for the rejection of the homosexual by society. That is most conspicuously the case where self-consciousness, display, or other ostentation characterizes the public conduct of homosexuals, as it does, to mention the notorious examples, with the elegant queens, the screaming faggots and the Mattachine Society crowd. Mind you, I am no judge of any of those who so behave: the question I raise is, rather, how much such behavior evidences radical self-rejection and, at the same time, solicits social rejection.

While again we cannot know the internal struggles Stringfellow faced regarding his sexual identity and practice, it is helpful to read this passage in the context of that day. The George Henry Foundation and some elements of the Mattachine Society saw their mission as helping the homosexual man (they did focus mostly on men) conform to societal norms and practices. They believed that persecution faced by homosexuals was related to their “deviant” behavior, the fact that they could be readily identified as contrary to heterosexual norm. Therefore, the way to overcome persecution was for these men to learn to behave in an acceptable manner so that they could “pass” as straight. In addition, from a theological perspective we can speculate that Stringfellow thought that sexuality could become idolatry, indicative of the principalities and powers. Stringfellow asserted that God’s grace accepted him as he was; converting to Christ brought a freedom to sexuality, being free to love wholly.

Stringfellow continued to practice law in East Harlem until the mid-1960s. Then he formed a law practice with two Harvard Law School colleagues, William Ellis and Frank Patton, which absorbed the East Harlem caseload and diversified into other cases. This helped Stringfellow established more manageable hours for legal practice and set aside time for writing and speaking engagements.

Indicative of the diversity of his interests, Stringfellow became a close friend and advocate for the controversial Episcopal Bishop James Pike. Pike, who had long been a strong advocate for progressive causes, like equal rights for African-American and ordination for women, drew on public media as a means to proclaim a more populist faith, but didn’t always use the media wisely. He also had a messy personal life. His fellow bishops began to accuse him of heresy leading up to a confrontation with the House of Bishops in October 1966 which censured Pike. Pike resigned as bishop and began a quest for the historical Jesus which led to his lonely death in a Middle Eastern desert in 1969. Stringfellow saw that Pike was a victim of the “principalities and powers.” Stringfellow and Towne co-authored The Bishop Pike Affair (1967) that chronicled the 1966 showdown between Pike and the bishops. Following Pike’s death, they did major research and co-authored an extensive biography, The Death and Life of Bishop James Pike (1976).

Stringfellow and Towne were contrasts physically—Towne was big and burly while Stringfellow was of more slight stature. The apartment they shared in Manhattan became a gathering place, a salon with frequent guests, discussions and parties. From his previous life Towne would have brought contacts in New York City’s gay circles. Towne, sometimes referred to as “a Methodist poet” also brought interests in Christian faith and thinking to their life together. Stringfellow wrote that they also shared a fondness for absurdity and fascination with paradox. They spent much of the summer of 1966 touring with a New England circus troupe. Stringfellow saw the circus as “a glimpse of the eschatological realm.”

Stringfellow’s health declined significantly during this time. During a trip to India back in 1953 he had contracted hepatitis. It was likely that vestiges of that disease gradually impaired his health, particularly his digestive system, in the years that followed. Stringfellow and Towne began looking for another home away from Manhattan in 1967. Stringfellow wrote that he was looking for a “monastery,” but they were certainly motivated to find a more tranquil living situation that might allow Stringfellow more opportunity for rest and recuperation. That fall they moved to a home on Block Island, Rhode Island. Towne proposed that they call this home “Eschaton” referring to the end of the world which is also the beginning of the Kingdom of God—a sign of hope.

Stringfellow had been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in Religion in 1967. He intended this to be a sabbatical, a major cutback in responsibilities at the law firm and a study trip to Eastern Europe as well as to Cambridge. But by the spring of 1968, after suffering major weight loss and extreme fatigue, he was admitted to Roosevelt Hospital for extensive tests. The diagnosis was that his digestive system was largely nonfunctional and he was suffering from malnutrition. He was sent home with an extensive regimen of therapy and dietary supplements. However, this treatment did not work and instead led to regular and excruciating pain. Then Stringfellow went back to the hospital for major surgery to remove his spleen and much of his pancreas.

In May 1968, in an antiwar protest, nine Catholic activists walked into the offices of the Selective Service in Catonsville, Maryland, removed some draft records and destroyed them in the parking lot outside. Police arrived and arrested the nine protestors. When the protestors were brought to trial in October 1968, four of them, including Fr. Daniel Berrigan, had gone underground and didn’t show up for the trial. Berrigan was sheltered by sympathizers in several places as he continued speaking out against the war. He spent some time on Block Island with Stringfellow where he was found by authorities and arrested on August 11, 1970. Weeks later, on December 17, 1970, Stringfellow and Towne were arrested for “harboring a fugitive.” They held a press conference at Eschaton to tell their story. The charges against them were ultimately dropped. Together they wrote a book about the experience, Suspect Tenderness: The Ethics of the Berrigan Witness (1971).

Stringfellow had long been a public advocate for the ordination of women in the Episcopal Church. He served as legal counsel to the 11 women who were irregularly ordained in Philadelphia in 1974. The General Convention in 1976 reached a compromise in which the 11 women would be received as priests, but would need to be re-ordained. Stringfellow drew on all his political acumen to challenge the bishops on the requirement for re-ordination. They subsequently reversed that decision.

Stringfellow has been often described as “almost but not quite out.” Undoubtedly, the relationship between Stringfellow and Towne was complex and multi-dimensional. Heather White writes about how Christian traditions of spiritual brotherhood could shelter same-sex love from social scrutiny. Stringfellow addressed the National Convention of Integrity (LGBT Episcopal group) in 1979, but did not identify himself as a gay man. He said “[the] matter of sexual proclivity and the prominence of the sexual identity of a person, are both highly overrated.” Consequently, he continued, “the issue is not homosexuality but sexuality in any and all of its species [because] there are as many varieties of sexuality as there be human beings.”

Stringfellow’s world came crashing down when Towne died unexpectedly on January 28, 1980. Towne had been nursing a mild case of the flu for a couple days. Stringfellow was scheduled to give a lecture at the University of Western Ontario. Assuming that Towne would rest and recover, Stringfellow traveled to his speaking engagement. However, Towne’s condition worsened dramatically and quickly. The rescue squad took him to the hospital where he died. Stringfellow received an urgent call to return home but did not get to see Towne before his death at the age of 51.

Stringfellow never fully recovered from the loss of Towne. Despite his increasingly incapacitated condition due to severe diabetes and other physical maladies, he would not have anyone else live with him. He wrote A Simplicity of Faith: My Experience in Mourning (1971) as his expression of mourning for Towne. Herein he referred to Towne as “my sweet companion for seventeen years.” He described their relationship as “monastic.” His health continued to deteriorate and Stringfellow died on March 2, 1985.

My published books: