Partner Honora Sneyd Edgeworth

Queer Places:

Cathedral & Bishop’s Palace, 19A The Close, Lichfield WS13 7LD, Regno Unito

Anna

Seward (12 December 1742[1] –

25 March 1809) was a long-eighteenth-century English Romantic poet, often

called the Swan of Lichfield. In a sonnet sequence addressed to her beloved Honora Sneyd,

written over a period of several years before and after Sneyd's marriage to

Richard Edgeworth, Anna

Seward described her sense of bertrayal at the marriage and her fears of

further loss in the future. In 1796, Anna

Seward published a poem entitled Llangollen Vale, praising the vestal

lustre of the sacred Friendship of

Eleonor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby

.

Anna

Seward (12 December 1742[1] –

25 March 1809) was a long-eighteenth-century English Romantic poet, often

called the Swan of Lichfield. In a sonnet sequence addressed to her beloved Honora Sneyd,

written over a period of several years before and after Sneyd's marriage to

Richard Edgeworth, Anna

Seward described her sense of bertrayal at the marriage and her fears of

further loss in the future. In 1796, Anna

Seward published a poem entitled Llangollen Vale, praising the vestal

lustre of the sacred Friendship of

Eleonor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby

.

Seward was the eldest of two surviving daughters of Thomas Seward (1708–1790), prebendary of Lichfield and Salisbury, and author, and his wife Elizabeth.[4][3] Elizabeth Seward later had three further children (John, Jane and Elizabeth) who all died in infancy, and two stillbirths.[2] Anna Seward mourned their loss in her poem Eyam (1788).[5] Born in 1742 at Eyam, a small mining village in the Peak District of Derbyshire where her father was the rector,[4] she and her sister Sarah, some sixteen months younger than she was, passed nearly all their life in the relatively small area of the Peak District of Derbyshire and Lichfield, a cathedral city in the adjacent county of Staffordshire to the west, an area now corresponding to the boundary of the East Midlands and West Midlands regions.[6][4]

In 1749 her father was appointed to a position as Canon-Residentiary at Lichfield Cathedral, and the family moved to that city, where her father educated her entirely at home. In 1754 they moved to the Bishop's Palace in the Cathedral Close. When a family friend, Mrs. Edward Sneyd, died in 1756,[1] the Sewards took in one of her daughters, Honora Sneyd, who became an 'adopted' foster sister to Anna.[7] Honora was nine years younger than Anna. Anna Seward describes how she and her sister first met Honora, on returning from a walk, in her poem The Anniversary (1769).[8] Sarah (known as 'Sally') died suddenly at the age of nineteen of typhus (1764).[9] Sarah was said to be of admirable character, but less talented than her sister.[10] Anna consoled herself with her affection for Honora Sneyd, as she describes in Visions, written a few days after her sister's death. In the poem she expresses the hope that Honora ('this transplanted flower') will replace her sister (whom she refers to as 'Alinda') in her and her parents affections.[11]

Anna Seward continued to live at the Bishop's Palace all her life, caring for her father during the last ten years of his life, after he had suffered a stroke. When he died in 1790, he left her financially independent with an income of ₤400 per annum. She spent the rest of her life at the Palace, till her death in 1809.[6]

A long-time friend of the Levett family of Lichfield, Seward noted in her Memoirs of the Life of Dr. Darwin (Erasmus) that three of the town's foremost citizens had been thrown from their carriages and had injured their knees in the same year. "No such misfortune," Seward wrote, "was previously remembered in that city, nor has it recurred through all the years which since elapsed."

In her early childhood, she was considered a precocious, sensitive redhead, and her bent for learning became evident from the beginning. Canon Seward held progressive views on female education, having authored The Female Right to Literature (1748).[12] Encouraged by her father, she was said to be able to recite the works of Milton by the age of three.[4]

Bishop's Palace, Lichfield

|

|

Even at the age of seven, when the family moved to Lichfield, she recognised she had a gift for writing. At Lichfield, the family later lived in the Bishop's Palace, which became the centre of a literary circle including Erasmus Darwin, Samuel Johnson and James Boswell, to which Anna was exposed and encouraged to participate, as she later relates.[13][10] Though Canon Seward's (but not his wife's) attitudes towards the education of girls was progressive relative to the times, they were not excessively liberal. Amongst the subjects he taught them were theology and numeracy, and how to read and appreciate poetry, and also how to write and recite poetry. Although this deviated from what were considered 'conventional drawing room accomplishments', the omissions were also notable, including languages and science, although they were left free to pursue their own inclinations.[14] However Anna was not unskilled in the domestic sphere.[15]

Among the many literary figures of the time with which she conversed was Sir Walter Scott, who would later publish her poetry posthumously. Her circle also included writers such as Thomas Day, Francis Noel Clarke Mundy, Sir Brooke Boothby and Willie Newton (the Peak Minstrel),[16] and she was considered the leader of a coterie of regional poets, and was influenced by writers such as Thomas Whalley, William Hayley, Robert Southey, Helen Maria Williams, Hannah More and the Ladies of Llangollen.[16][6] In addition to her literary circle, she was involved in the deliberations of the Lunar Society in nearby Birmingham, that would sometimes meet at her father's home.[17] Both Darwin and Day were members of the Lunar Society and the Lichfield coterie, while Seward would correspond with other Lunar members such as Josiah Wedgewood and Richard Lovell Edgeworth.[16]

Between 1775 and 1781, Seward was a guest and participant at the much-mocked salon held by Anna Miller at Batheaston, near Bath. However, it was here that Seward's talent was recognised and her work published in the annual volume of poems from the gatherings, a debt that Seward acknowledged in her Poem to the Memory of Lady Miller (1782).[18]

Seward remained resolutely single throughout her life, despite many offers, and friendships, and was quite outspoken about the institution of marriage,[13][4] not unlike her heroine in Louisa,[19] a position that would later be echoed in the novels of her step-niece, Maria Edgeworth. She shunned both marriage and sexual love, as inferior to Aristotelian friendship, based more on equality and virtue. However she had friends of both genders, although only seeking romantic relationships with women.[20] In 1985 Lillian Faderman suggested that her orientation was lesbian,[21] although there is little known evidence of either the erotic or sexual, in her relationships, though the term relates more to twentieth rather than eighteenth century concepts of identity. However, since 1985 Seward remains within the lesbian poetic canon.[20] However Teresa Barnard argues against this based more on examination of her correspondence than merely her poetry,[13] while more recently Barrett has argued for it, based on other sources.[20]

Much of the literature on Seward's relationship focusses on her childhood friend Honora Sneyd, the sonnets revealing her passion for her when they were together and her despair when Sneyd married Richard Edgeworth. Compared to the correspondence, her sonnets display much more intense emotion, such as Sonnet 10 [Honora, shou’d that cruel time arrive] describing her feelings of betrayal. When the Edgeworths returned to Ireland, despair turned to rage, as in Sonnet 14 [Ingratitude, how deadly is thy smart].[20]

After her death, Sir Walter Scott edited Seward's Poetical Works in three volumes (Edinburgh, 1810).[26] To these he prefixed a memoir of the author, adding extracts from her literary correspondence. Scott's editing demonstrates considerable censorship[37] and he declined to edit the bulk of her letters, which were later published in six volumes by Archibald Constable as Letters of Anna Seward 1784–1807 (1811).[23][29] Her reputation barely lasted beyond her life, although there has been a renewed interest in the twenty first century. There was a tendency to be dismissive of her work in early twentieth century criticism, [38] but later, particularly amongst feminist scholars, she was seen as a valuable observer of gendered relationships in late eighteenth century society, and played a transitional role between late eighteenth century principles and emerging romanticism. Likewise, her engagement with the political, cultural and literary issues of the time gives her a role in reflecting the responses of society to those issues.[6][39] Kairoff, considering her "one of the - in a literal sense - ultimate eighteenth century poets".[40]

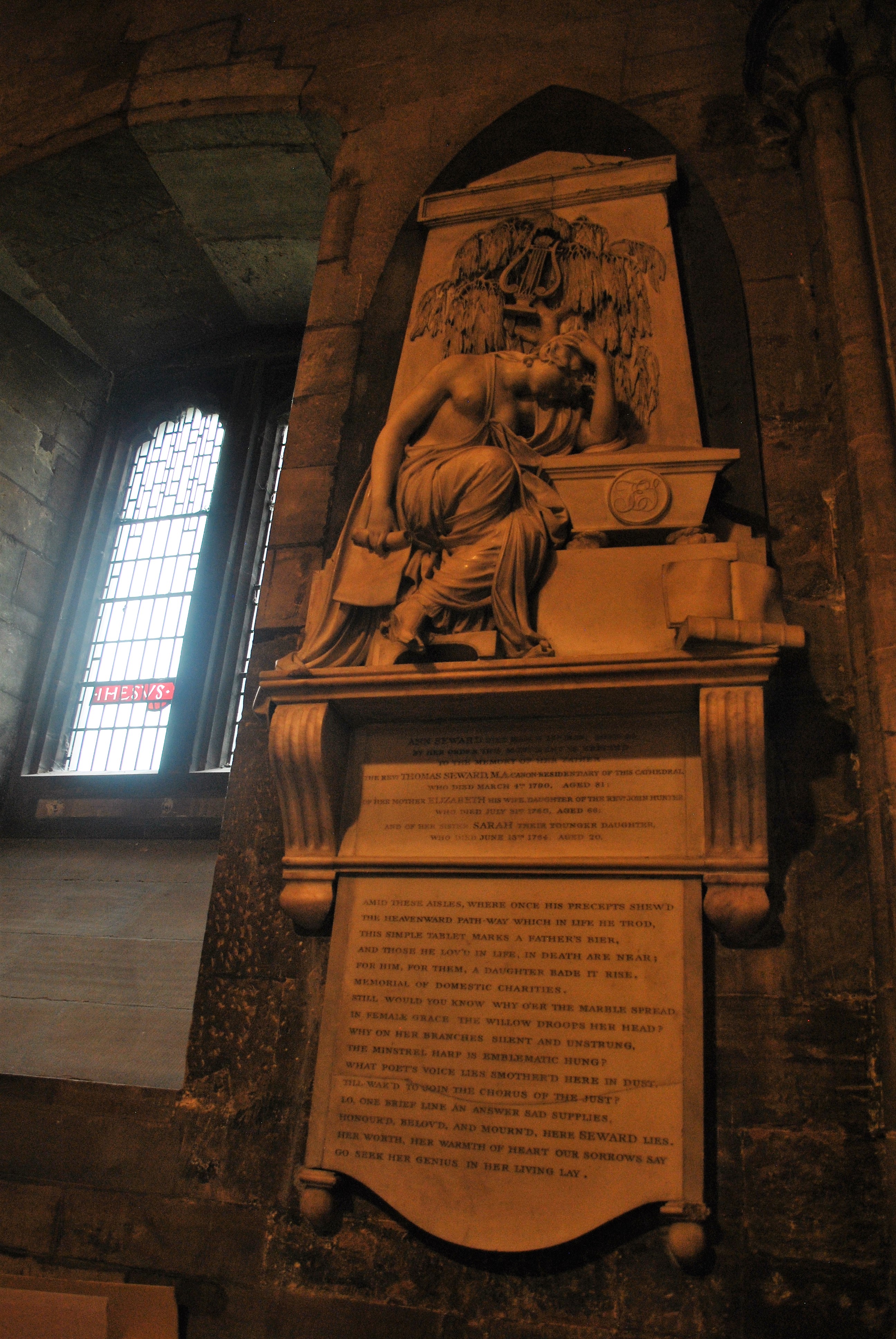

There is a plaque to Anna Seward (spelled "Ann") in Lichfield Cathedral. The epitaffio has been written by her friend Walter Scott, author of Ivanhoe. Seward appears as a character in the novel The Ladies by Doris Grumbach (1984).[41]

My published books: