Queer Places:

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

AKA Marylebone, 5 Bentinck St, Marylebone, London W1U 2EG, Regno Unito

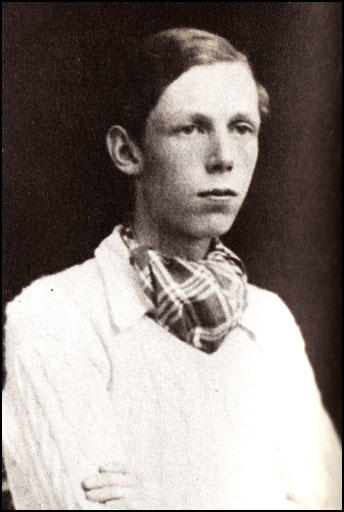

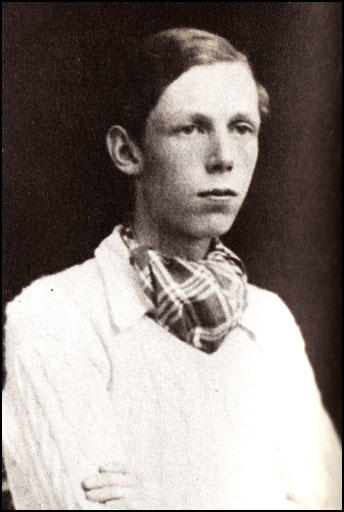

Anthony Frederick Blunt (26 September 1907 – 26 March 1983),[1]

known as Sir Anthony Blunt, KCVO, from 1956 to 1979, was a leading British art

historian who in 1964, after being offered immunity from prosecution,

confessed to having been a Soviet spy. He was part of the

Cambridge Apostles. The item on ‘Homosexuality’ in Norman

Polmar and Thomas B. Allen’s generally reliable Encyclopedia of Espionage

(1998) names just nine homosexual men and one bisexual:

Alfred Redl,

Guy Burgess, the bisexual

Donald Maclean,

Anthony Blunt,

Alan Turing, James A.

Mintkenbaugh, William Martin,

Bernon Mitchell,

John Vassall and

Maurice Oldfield. The

last-named had to resign his position as co-ordinator of UK security and

intelligence in Northern Ireland after he was found to be homosexual; there

was no suggestion that in his previous incarnation as Director General of MI6

he ever spied for anyone but his own Whitehall masters.

Anthony Frederick Blunt (26 September 1907 – 26 March 1983),[1]

known as Sir Anthony Blunt, KCVO, from 1956 to 1979, was a leading British art

historian who in 1964, after being offered immunity from prosecution,

confessed to having been a Soviet spy. He was part of the

Cambridge Apostles. The item on ‘Homosexuality’ in Norman

Polmar and Thomas B. Allen’s generally reliable Encyclopedia of Espionage

(1998) names just nine homosexual men and one bisexual:

Alfred Redl,

Guy Burgess, the bisexual

Donald Maclean,

Anthony Blunt,

Alan Turing, James A.

Mintkenbaugh, William Martin,

Bernon Mitchell,

John Vassall and

Maurice Oldfield. The

last-named had to resign his position as co-ordinator of UK security and

intelligence in Northern Ireland after he was found to be homosexual; there

was no suggestion that in his previous incarnation as Director General of MI6

he ever spied for anyone but his own Whitehall masters.

Blunt had been a member of the Cambridge Five, a group of spies working for

the Soviet Union from some time in the 1930s to at least the early 1950s. His

confession, a closely held secret for many years, was revealed publicly by

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in November 1979. He was stripped of his

knighthood immediately thereafter.

Blunt was Professor of the History of Art at the University of London,

director of the Courtauld Institute of Art, and Surveyor of the Queen's

Pictures. His 1967 monograph on the French Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin is

still widely regarded as a watershed book in art history.[2]

His teaching text and reference work Art and Architecture in France

1500–1700, first published in 1953, reached its fifth edition in a

slightly revised version by Richard Beresford in 1999, when it was still

considered the best account of the subject.[3]

Blunt was born in Bournemouth, Dorset, the third and youngest son of a

vicar, the Revd (Arthur) Stanley Vaughan Blunt (1870–1929), and

Hilda Violet (1880–1969), daughter of Henry Master of the Madras civil

service. He was the brother of writer

Wilfrid Jasper Walter Blunt and of

numismatist Christopher Evelyn Blunt, and the grandnephew of poet Wilfrid

Scawen Blunt.

He was a third cousin of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, the late Queen Mother: his

mother was the second cousin of Elizabeth's father Claude Bowes-Lyon, 14th

Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne. On occasions, Blunt and his two brothers,

Christopher and Wilfrid, took afternoon tea at the Bowes-Lyons' London home at

17 Bruton Street, Mayfair, the birthplace of Queen Elizabeth II.[4]

He was fourth cousin once removed of Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley (1896-1980)

6th Baronet, leader of the British Union of Fascists, both being descended

from John Parker Mosley (1722-1798).

Blunt's vicar father was assigned to Paris with the British embassy chapel,

and so moved his family to the French capital for several years during Blunt's

childhood. The young Anthony became fluent in French, and experienced

intensely the artistic culture closely available to him, stimulating an

interest which lasted a lifetime and formed the basis for his later career.[5]

He was educated at Marlborough College, where he joined the college's

secret 'Society of Amici',[6]

in which he was a contemporary of Louis MacNeice (whose unfinished

autobiography The Strings are False contains numerous references to

Blunt), John Betjeman

and Graham Shepard. He was remembered by historian John Edward Bowle, a year

ahead of Blunt at Marlborough, as an intellectual prig, too preoccupied with

the realm of ideas. He thought Blunt had too much ink in his veins and

belonged to a world of rather prissy, cold-blooded, academic puritanism.[5]

He won a scholarship in mathematics to Trinity College, Cambridge. At that

time, scholars in Cambridge University were allowed to skip Part I of the

Tripos and complete Part II in two years. However, they could not earn a

degree in less than three years,[7]

hence Blunt spent four years at Trinity and switched to Modern Languages,

eventually graduating in 1930 with a first class degree. He taught French at

Cambridge and became a Fellow of Trinity College in 1932. His graduate

research was in French art history and he travelled frequently to continental

Europe in connection with his studies.[5]

Like Guy Burgess,

Blunt was known to be homosexual,[8]

which was a criminal activity at that time in Britain. Both were members of

the Cambridge Apostles (also known as the Conversazione Society), a

clandestine Cambridge discussion group of 12 undergraduates, mostly from

Trinity and King's Colleges who considered themselves to be the brightest

minds in the university. Many were homosexual and Marxist at that time.

Amongst other members, also later accused of being part of the Cambridge spy

ring, were the American Michael Whitney Straight and

Victor Rothschild who later worked for MI5.[9]

Rothschild gave Blunt £100 to purchase Eliezar and Rebecca by Nicolas

Poussin.[10]

The painting was sold by Blunt's executors in 1985 for £100,000 (totalling

£192,500 with tax remission[11])

and is now in the Fitzwilliam Museum.[12]

There are numerous versions of how Blunt was recruited to the NKVD. As a

Cambridge don, Blunt visited the Soviet Union in 1933, and was possibly

recruited in 1934. In a press conference, Blunt claimed that

Guy Burgess recruited him

as a spy.[13]

Many sources suggest that Blunt remained at Cambridge and served as a

talent-spotter. He may have identified Burgess,

Kim Philby,

Donald Maclean,

John Cairncross and Michael Straight – all undergraduates at Trinity College a

few years younger than he – as potential spies for the Soviets.[5]

Blunt said in his public confession that it was Burgess who converted him

to the Soviet cause, after both had left Cambridge.[14]

Both were members of the Cambridge Apostles, and Burgess could have recruited

Blunt or vice versa either at Cambridge University or later when both worked

for British intelligence.

Blunt died of a heart attack at his London home in 1983, aged 75.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Blunt

- Woods, Gregory. Homintern . Yale University Press. Edizione del

Kindle.

Anthony Frederick Blunt (26 September 1907 – 26 March 1983),[1]

known as Sir Anthony Blunt, KCVO, from 1956 to 1979, was a leading British art

historian who in 1964, after being offered immunity from prosecution,

confessed to having been a Soviet spy. He was part of the

Cambridge Apostles. The item on ‘Homosexuality’ in Norman

Polmar and Thomas B. Allen’s generally reliable Encyclopedia of Espionage

(1998) names just nine homosexual men and one bisexual:

Alfred Redl,

Guy Burgess, the bisexual

Donald Maclean,

Anthony Blunt,

Alan Turing, James A.

Mintkenbaugh, William Martin,

Bernon Mitchell,

John Vassall and

Maurice Oldfield. The

last-named had to resign his position as co-ordinator of UK security and

intelligence in Northern Ireland after he was found to be homosexual; there

was no suggestion that in his previous incarnation as Director General of MI6

he ever spied for anyone but his own Whitehall masters.

Anthony Frederick Blunt (26 September 1907 – 26 March 1983),[1]

known as Sir Anthony Blunt, KCVO, from 1956 to 1979, was a leading British art

historian who in 1964, after being offered immunity from prosecution,

confessed to having been a Soviet spy. He was part of the

Cambridge Apostles. The item on ‘Homosexuality’ in Norman

Polmar and Thomas B. Allen’s generally reliable Encyclopedia of Espionage

(1998) names just nine homosexual men and one bisexual:

Alfred Redl,

Guy Burgess, the bisexual

Donald Maclean,

Anthony Blunt,

Alan Turing, James A.

Mintkenbaugh, William Martin,

Bernon Mitchell,

John Vassall and

Maurice Oldfield. The

last-named had to resign his position as co-ordinator of UK security and

intelligence in Northern Ireland after he was found to be homosexual; there

was no suggestion that in his previous incarnation as Director General of MI6

he ever spied for anyone but his own Whitehall masters.