Partner

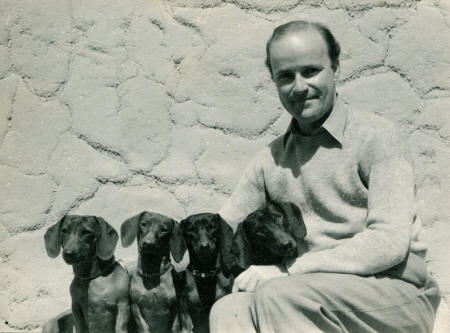

Myron Brinig,

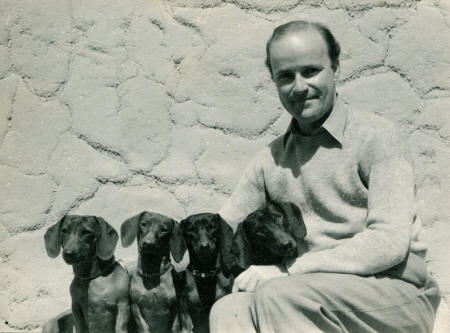

Fritz Peters

Queer Places:

Casa Las Barrancas, 15 Cam Ancon, Santa Fe, NM 87506

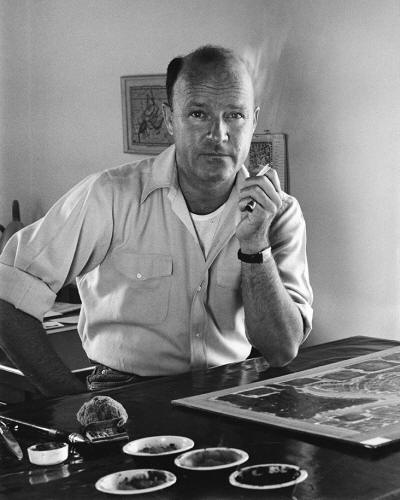

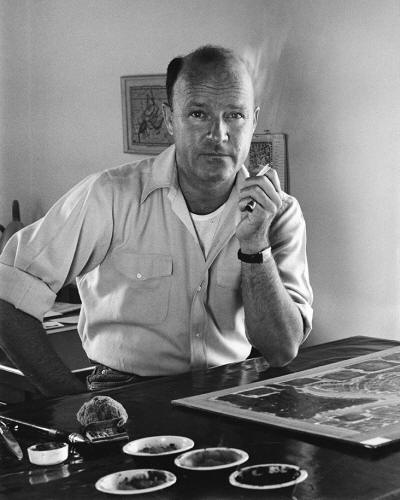

Henry Cady Wells (November 15, 1904 - November 5, 1954) was a notable painter, patron of the arts, and activist citizen of the Santa Fe and Taos art

colonies. When Wells settled in New Mexico in 1932, he became part of a thriving community of queer (and

straight) writers, artists, and patrons of the arts that included writer

Myron Brinig, poets

Witter Bynner and

Spud Johnson, painter

Georgia O'Keeffe, and arts patron

Mabel Dodge Luhan. While

living in Taos, Wells restored an old Spanish home at Jacona, Casa Las

Barrancas, some twenty

miles north of Santa Fe, and there gained a reputation as a magnificent host.

He was clever, witty, affectionate, and generous; he anonymously aided

numerous individuals during the post-depression and war years. Many in the

community sought him out as a guest and a friend. Wells was a close friend, mentor and adviser to

Martha Graham, the modern dancer and choreographer (She married dancer Erick Hawkins in the little chapel on the Casa Barrancas property).

Henry Cady Wells (November 15, 1904 - November 5, 1954) was a notable painter, patron of the arts, and activist citizen of the Santa Fe and Taos art

colonies. When Wells settled in New Mexico in 1932, he became part of a thriving community of queer (and

straight) writers, artists, and patrons of the arts that included writer

Myron Brinig, poets

Witter Bynner and

Spud Johnson, painter

Georgia O'Keeffe, and arts patron

Mabel Dodge Luhan. While

living in Taos, Wells restored an old Spanish home at Jacona, Casa Las

Barrancas, some twenty

miles north of Santa Fe, and there gained a reputation as a magnificent host.

He was clever, witty, affectionate, and generous; he anonymously aided

numerous individuals during the post-depression and war years. Many in the

community sought him out as a guest and a friend. Wells was a close friend, mentor and adviser to

Martha Graham, the modern dancer and choreographer (She married dancer Erick Hawkins in the little chapel on the Casa Barrancas property).

Primarily self-taught, Wells developed first a regional and then a national reputation for his watercolor

paintings, some 400 of which he created during his short career, which spans the years 1932 to 1954.

During the Great Depression, Wells provided philanthropy for artists, as well as for his Hispanic neighbors,

while also supporting the careers of gay composer

David Diamond (who dedicated a chamber orchestra

piece to him) and dancer/choreographer Martha Graham.

Wells's donation of some 200 carved and painted wooden folk saints (Santos) to the Museum of New Mexico

in 1952 formed one of the core collections of the Museum of International Folk Art and the Museum of

Spanish Colonial Arts in Santa Fe.

A child of wealth and privilege, Wells was born on November 15, 1904, to a family that built the American

Optical Company in Southbridge, Massachusetts, and later founded Sturbridge Village, a living history

museum of pre-industrial colonial New England.

Wells was the family rebel, dropping out of five boarding schools and never fitting into any of the scenarios

that his conservative Republican family had planned for him. Instead, both he and his younger (also gay)

brother Mason Wells devoted their lives to the arts.

Cady's father sent him to the Evans School in Arizona in the mid-1920s, hoping that ranch life would make

him more manly. Instead, Wells fell in love with the desert and mountain landscapes of the Southwest and

began to paint.

The young Cady Wells was conflicted about his sexuality and contemptuous of "fairies," the category into

which he seems to have been placed by some of his tormenting peers. In Santa Fe, he would find a place

where he could be gay and accepted.

Wells tried a number of occupations in the late 1920s before taking a tour to Japan, China, and Bali in

1932. Passing through northern New Mexico on his return, he decided to study painting with Santa Fe's most

famous modernist painter, Andrew Dasburg.

Under Dasburg's tutelage, Wells produced vibrant expressionist watercolors of the mountains and mesas

that show the influence of Asian art, as well as his training as a classical musician.

In 1933, Wells met the Jewish-American writer

Myron Brinig, who became his lover. They parted ways in 1935, when Wells spent two months in Japan studying ink brush techniques. On his return, Wells bought

property in Jacona, some twenty miles north of Santa Fe, where he created a compound that became one

of the central social gathering spots for the arts communities and visiting celebrities.

In 1935 and 1936, Wells began to develop a series of highly original works that reflected his fascination with

the darker rituals and legends embedded in the fabric of New Mexico's history and landscape, as well as

with the Santos he collected. These included the lay brotherhood of the Penitentes, who observed their

Hispanic folk Catholicism in closed moradas (meeting places), and who practiced self-flagellation during

their Easter services.

Like other gay artists of his time, particularly Seattle painter

Morris Graves, Wells used a coded language to

express wounds that were both deeply personal, and--during and after World War II--responsive to the

global horrors unleashed by the war. The blood reds, dark browns, and acid greens of his religiously themed

and landscape paintings stand apart from any of the work done by his New Mexico modernist

contemporaries.

In 1941, at age 36, Wells volunteered for the U.S. Army. Deployed in Germany during the last nine months

of the war, he made aerial topographical maps, which would have a profound impact on his style after the

war. Traumatized by the violence and death he witnessed, he returned home in 1945 to discover that

neighboring Los Alamos (twelve miles from his home) had created the atomic bomb.

The labs expanded their work on nuclear weapons after the war, and often detonated conventional bombs

several times a day, which sometimes shook the rafters of Wells's home, and sent what he described as

mushroom-shaped clouds over his beloved mesas.

Between 1947 and 1951, Wells wintered in St. Croix, and engaged in two long-term affairs, his last with

Fritz Peters, a writer who authored Finistère, a remarkable novel about homosexuality.

Wells's postwar paintings responded to the angst of the Atomic Age with references to barbed wire and the

transformation of landforms into weapons, while others suggested prehistoric creatures, or the petroglyphs

that mark the desert landscapes of the Southwest, reminders of the creativity and fragility of former

civilizations.

Between 1947 and 1953 Wells gained a national reputation, and was included in important exhibitions in

New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco, along with other members of the American avant-garde,

including (now) much better known artists such as Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, Adolph Gottlieb, and Jackson

Pollack.

Wells suffered a heart attack in the spring of 1953, and died of heart failure on November 5, 1954, ten days

before his fiftieth birthday.

From 1933 to 1953, Wells was given 21 one-man exhibitions and he was included in 70 group exhibitions in

every region of the country.

His works are in the collections of major museums throughout the U.S., including the Smithsonian, the Art

Institute of Chicago, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and the Whitney Museum of Art.

After his death, one of his closest friends, the arts entrepreneur

Merle Armitage, wrote to Wells's father

that Cady was the only modern artist who "got under the skin of New Mexico," expressing its history and

culture with a truth that spoke significantly to both his place and his time.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- Cady Wells -

Wikipedia

- Wells, Cady (1904-1954)

by Lois Rudnick

Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc.

Entry Copyright © 2008 glbtq, Inc.

Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com

Henry Cady Wells (November 15, 1904 - November 5, 1954) was a notable painter, patron of the arts, and activist citizen of the Santa Fe and Taos art

colonies. When Wells settled in New Mexico in 1932, he became part of a thriving community of queer (and

straight) writers, artists, and patrons of the arts that included writer

Myron Brinig, poets

Witter Bynner and

Spud Johnson, painter

Georgia O'Keeffe, and arts patron

Mabel Dodge Luhan. While

living in Taos, Wells restored an old Spanish home at Jacona, Casa Las

Barrancas, some twenty

miles north of Santa Fe, and there gained a reputation as a magnificent host.

He was clever, witty, affectionate, and generous; he anonymously aided

numerous individuals during the post-depression and war years. Many in the

community sought him out as a guest and a friend. Wells was a close friend, mentor and adviser to

Martha Graham, the modern dancer and choreographer (She married dancer Erick Hawkins in the little chapel on the Casa Barrancas property).

Henry Cady Wells (November 15, 1904 - November 5, 1954) was a notable painter, patron of the arts, and activist citizen of the Santa Fe and Taos art

colonies. When Wells settled in New Mexico in 1932, he became part of a thriving community of queer (and

straight) writers, artists, and patrons of the arts that included writer

Myron Brinig, poets

Witter Bynner and

Spud Johnson, painter

Georgia O'Keeffe, and arts patron

Mabel Dodge Luhan. While

living in Taos, Wells restored an old Spanish home at Jacona, Casa Las

Barrancas, some twenty

miles north of Santa Fe, and there gained a reputation as a magnificent host.

He was clever, witty, affectionate, and generous; he anonymously aided

numerous individuals during the post-depression and war years. Many in the

community sought him out as a guest and a friend. Wells was a close friend, mentor and adviser to

Martha Graham, the modern dancer and choreographer (She married dancer Erick Hawkins in the little chapel on the Casa Barrancas property).