Partner Guy Anderson, Sherrill Kinney Van Cott, Malcom Roberts, Yonemitsu "Yone" Arashiro, Paul Mills, Richard Svare

Queer Places:

909 E Mercer St, Seattle, WA 98102

5217 21st Ave NE, Seattle, WA 98105

415 Caledonia St, La Conner, WA 98257

186th Pl SW, Edmonds, WA 98026

The Rock, Rodger Bluff, WA 98221

136 Melrose Ave E, Seattle, WA 98102

Careladen, 10830 Wachusett Rd, Woodway, WA 98020

Woodtown Manor, Stocking Ln, Rathfarnham, Dublin 16, Ireland

Pletscheff Mansion, E Highland Dr & Broadway E, Seattle, WA 98102

The Lake, Loleta, CA 95551

Morris Graves Museum of Art, 636 F St, Eureka, CA 95501

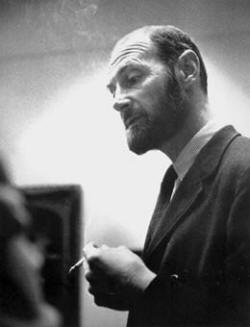

Morris Graves (August 28, 1910 – May 5, 2001) was an American painter. He was one of the earliest Modern artists from the Pacific Northwest to achieve national and international acclaim. His style, referred to by some reviewers as Mysticism, used the muted tones of the Northwest environment, Asian aesthetics and philosophy, and a personal iconography of birds, flowers, chalices, and other images to explore the nature of consciousness.

An article in a 1953 issue of Life magazine cemented Graves' reputation as a major figure of the 'Northwest School' of artists. He lived and worked mostly in Western Washington, but spent considerable time traveling and living in Europe and Asia, and spent the last several years of his life in Loleta, California.[1][2][3]

Morris Graves (August 28, 1910 – May 5, 2001) was an American painter. He was one of the earliest Modern artists from the Pacific Northwest to achieve national and international acclaim. His style, referred to by some reviewers as Mysticism, used the muted tones of the Northwest environment, Asian aesthetics and philosophy, and a personal iconography of birds, flowers, chalices, and other images to explore the nature of consciousness.

An article in a 1953 issue of Life magazine cemented Graves' reputation as a major figure of the 'Northwest School' of artists. He lived and worked mostly in Western Washington, but spent considerable time traveling and living in Europe and Asia, and spent the last several years of his life in Loleta, California.[1][2][3]

“The Lavender Palette: Gay Culture and the Art of Washington State” at the Cascadia Museum in Edmonds was a packed art show and a powerful history lesson. Museum curator David F. Martin put together artwork by dozens of gay men and women who often, just a few short decades ago, had to hide who they were in order to express themselves artistically. The exhibit closed on January 26, 2020. The featured artists included Edmonds native Guy Anderson, illustrator Richard Bennett, Ward Corley, Thomas Handforth, Mac Harshberger, Jule Kullberg, Delbert J. McBride, Orre Nelson Nobles, Malcolm Roberts, potter Lorene Spencer, Sarah Spurgeon, ceramicist Virginia Weisel, Clifford Wright, and also one-time Woodway resident Morris Graves, Leo Kenney, Mark Tobey, Lionel Pries, Leon Derbyshire, and Sherrill Van Cott.. The Morris Graves painting “Preening Sparrow” was featured in the famous Life magazine story about Northwest School artists Anderson, Graves, Tobey and their straight friend Kenneth Callahan.

Morris Graves called artists Jan Thompson, Richard Gilkey, and Ward Corley, the playful Otters; with them he was loving, funny, generous, and intense loyal, and they all rallied to his care if necessary.

Morris Cole Graves was born August 28, 1910, in Fox Valley, Oregon, where his family had moved about a year before his birth, from Seattle, Washington, in order to claim land under the Homestead Act. He was named in honor of Morris Cole, a favored minister of his Methodist parents. He had five older brothers, and eventually, two younger siblings.[2][3] Constant winds and cold winters made it much more difficult than expected to establish a working farm, and the struggle led to bankruptcy of the senior Graves' once-thriving paint and wallpaper store in Seattle. In 1911, a few months after Morris' birth, the family returned to the Seattle area,[3] settling north of the city in semi-rural Edmonds, Washington.[4] He was a self-taught artist with natural understandings of color and line. Graves dropped out of high school after his sophomore year, and between 1928 and 31, along with his brother Russell, visited all the major Asian ports of call as a steamship hand for the American Mail Line.[1] On arriving in Japan, he wrote: There, I at once had the feeling that this was the right way to do everything. It was the acceptance of nature not the resistance to it. I had no sense that I was to be a painter, but I breathed a different air.[5]

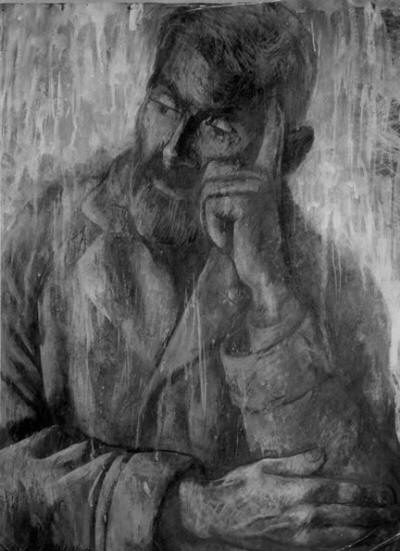

1949 - PORTRAIT OF MORRIS GRAVES

by Carlyle Brown

Gouache on paper

Private collection

In his early twenties, Graves finished high school in 1932 in Beaumont, Texas, while living with his maternal aunt and uncle. He then returned to Seattle, and received his first recognition as an artist when his painting Moor Swan (1933) won an award in the Seattle Art Museum's Northwest Annual Exhibition and was purchased by the museum.[2] He split his time between Seattle and La Conner, Washington, where he shared a studio with Guy Anderson. Graves' early work was in oils and focused on birds touched with strangeness, either blind, or wounded, or immobilized in webs of light.[5] Graves began his lifelong study of Zen Buddhism in the early 1930s.

In 1932 Graves and Guy Anderson were both living with their parents in Edmonds, just north of Seattle, and the two became lovers. To commemorate a three-way they had with artist Lionel Pries in the 1930s, Morris Graves and Guy Anderson made a two-sided watercolor — Graves’ nude study of Anderson on one side, Anderson’s study of Graves on the other.

In 1934, Graves built a small studio on family property in Edmonds, Washington. When it burned to the ground in 1935, almost all of his work to date was lost with it.

In the mid-1930s, Morris Graves met a handsome young man named Sherrill Kinney Van Cott from the small town of Sedro-Woolley, 72 miles north of Seattle. Van Cott had briefly attended the University of Washington after graduating from high school in 1931, but was largely a self-taught artist. He first began exhibiting in the Northwest Annuals at the Seattle Art Museum in 1935 with an oil painting titled Potato Eaters, while Graves also showed two oils. Both artists exhibited in the annuals for the next few years, and in 1939 Van Cott began to exhibit sculpture. The few extant sculptures by Van Cott, using regional materials, appear to have been influenced by the French sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, who had died at age 24 in WWI. Graves and Van Cott developed a romantic relationship, with Graves exerting a stylistic influence on the slightly younger artist. Van Cott was also a poet, and his writings were compatible with the visual content of his paintings. He focused on insects and other animals, both real and imagined, as well as complex intertwining of the male human form in a fossil-like contained border. Van Cott's last painting, a watercolor titled Weeping Girl, was exhibited at the Northwest Annual from October 7 through November 8, 1942. A month later, he was dead at age 29 from cardiac failure. 20 years earlier, Van Cott had contracted scarlet fever, which caused a severe hearth problem, leaving him practically an invalid for most of his short life. The local art scene had lost a promising talent, and Graves a lover and acolyte. He promoted Van Cott's work long after his death, and preserved many works in his own collection.

Graves' first one-man exhibition was in 1936 at the Seattle Art Museum (SAM);[2] that same year he began working under Bruce Inverarity at the Seattle unit of the WPA's Federal Art Project. His participation was sporadic, but it was there that he met Mark Tobey and became impressed with Tobey's calligraphic line. In January 1937 Graves traveled to New York City to study with the controversial Father Divine's International Peace Mission movement in Harlem; on his return, in May, he bought 20 acres (81,000 m2) on Fidalgo Island. In 1938 he quit the FAP and went to the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico to paint.[1] In 1940, Graves began building a house, which he named The Rock, on an isolated promontory on his Fidalgo Island property. He lived at The Rock with a succession of cats and dogs, all called Edith, in honor of poet Edith Sitwell.[2]

In the late 1930s, Malcom Roberts was in a romantic but open relationship with painter Morris Graves. In 1939 they moved into a home on Melrose Avenue East, on Seattle's Capitol Hill, with composer John Cage and his beard wife, Xenia. Roberts' high-strung personality was at odds with that of the mischievous Graves, so their living arrangement soon came to an end. Morris Graves, Guy Anderson, and Richard Bennett remained friends throughout the 1940s, and Graves would often visit the couple at their cabin at Robe Ranch, where they all shared ideas and produced work in the Northwest wilderness. Mark Tobey would also visit occasionally, but his disdain for outdoor activities led Margaret Callahan to remark: "Nature in the raw for Mark Tobey means dinner in the open at a city park such as Golden Gardens or Volunteer Park."

Graves was known for his personal charm and bursts of puckish humor, but also spent long periods in semi-isolation, absorbed in nature and his art. At the Rock, with the Second World War erupting, he retreated for a particularly long time and created a very large number of paintings. Many of them, such as Dove of the Inner Eye (1941) and Bird in the Night (1943), featured what would become Graves' iconic motif of birds trapped in layers of webbing or barbs, representing the artist's fears for the survival of man and nature in the face of modern industry and warfare. His near-isolation was interrupted in the Spring of 1942 when the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened its Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States exhibition. Critics raved over Graves' contributions, all of which were quickly snapped up by museums and collectors. At the same time the U.S. Army came looking for him, as he had failed to achieve the conscientious objector status he had applied for. There was also suspicion of him due to his association with the International Peace Mission and the fact that among his few regular visitors at the Rock had been the brilliant Japanese-American designer George Nakashima and his Japanese-born wife Miriam, prior to their being sent to the Minidoka relocation center. While his work was receiving further exhibition in New York and Washington D.C., and phenomenal sales, the artist himself spent much of that same time in the stockade at Camp Roberts, California, where he went into a deep depression. He was finally released from military service in March 1943.[1][2] With help from longtime supporters Elizabeth Willis, Nancy Ross, and Marian Willard, owner of the Willard Gallery in New York, Graves' work continued to enjoy popularity throughout the war years and beyond, with numerous exhibitions.[1] In the late 40s he purchased land in Woodway, Washington, and began construction of a unique cinderblock house he came to call "Careladen".[4]

In February 1945, Fortune magazine paid a small tribute to Van Cott and Graves, exposing the work to some of the younger generation of gay artists, like Leo Kenney and Ward Corley.

Graves received a Guggehheim Fellowship allowing him to study in Japan, but only made it as far as Hawaii before his entry was blocked by Japan's U.S. military occupation authorities. He spent several months in 1947 painting and learning the Japanese language in Hawaii. By the late 1940s Graves' and Mark Tobey's moment as the stars of the New York art world had faded, supplanted by the post-war rise of Action Painting and pure Abstraction.[1] In 1949 Graves sailed to England aboard RMS Mauretania, spending a month as the guest of art collector Edward James. He then spent three solitary winter months in France, sketching and painting the Chartres Cathedral. This austere interlude may have been in response to critical complaints of superficiality in his more recent paintings; however, after returning to Seattle in 1950, he destroyed most of his Chartres works.[2]

In the 1950s Graves was not faring very well in his love life. He had been involved with a man named Yonemitsu "Yone" Arashiro, who fell hopelessly in love with him but was taken aback at Graves' contradictory nature. The extant letters between the two men reveal a chronology of hopeful, romantic love, followed by Yone's desperate attempt to resign himself to a hopeless loss of the idea of romantic love. In a letter dated November 13, 1952, he wrote to Graves: "You are building your life with one justifiable selfishness. My downfall is that I need someone to love and share the hopes and dreams that belong to nowhere, no other, or even anywhere. A selfish love for two people, for their inner self alone. If I must walk this life alone, I would do so. I cannot comply or try to discharge this inner feeling. So, I am going to resign myself to a solitary life & live another kind of life void of all emotional ties." After Arashiro, Morris Graves met and fell in love with Paul Mills, a Seattle-born museum professional who had attended the University of Washington and was working at the university's Henry Art Gallery as assistant curator in 1952 and '53. Mills, who was 14 years younger than Graves, was living a closeted existence, but that didn't stop Graves from falling for him. Their relationship was brief but intense. Surving letters show Graves for once as the shunned partner. Mills addressed his conflict in an undated letter to Graves: "I'm at last beginning to learn something you have learned for yourself and have tried to tell me, the importance of calming down. I have also discovered, by watching myself and seeing what I get confused about and when I get along well, that homosexuality is something that creates too much of a strain on me and makes life difficult for me, hence I had better give that up. The next chapter of my life is going to be devoted to developing a nice, calm "middle". I have investigated the extremes of experiences a little too thoroughly." Graves responded: "This is what I cannot withhold letting you know: You are in my thoughts almost constantly, but those earlier thoughts which (during the months before winter) were set in motion by you (and willingly together) are now thoughts cheated of their long & urgently needed expressions. You have killed half of my heart, half of my spirit. You have replaced a kind of growing buoyancy with a negative vacancy. You have, at last, by your behaviour, put a kind of solid vacancy into my spirit, into my whole way of being & breathing & searching and that which in my life was, by you, once invited into a renewed living & expanding & creating experience has found finally only the drying effect of your smashing & that is why you, whom I loved, I now feel only hatred for." Mills, resigned to his stand, replied: "Morris, the answer seems to be "no" and quite a final one. And it would only make things more difficult for both of us if we were to see each other again." Mills went on to marry a woman and had children. They remained married until his wife's death in 1999, after which he came out as a homosexual and became an activist in California. His son, Mike Mills, wrote and directed an award-winning fulm titles Beginners in 2010 based on his father's complicated life. Within a few years of the end of his relationship with Mills, Graves met a young man named Richard Svare and had a long-term, productive relationship with him.

In 1952 photographer Dody Weston Thompson used part of her Albert M. Bender grant to photo document the unique home and surroundings of Graves, who she considered a close friend. In the Spring of 1953, Graves staged the first Northwest art "Happening", sending invitations to everyone on the Seattle Art Museum mailing list: You or your friends are not invited to the exhibition of Bouquet and Marsh paintings by the 8 best painters in the Northwest to be held on the afternoon and evening of the longest day of the year, the first day of summer, June 21, at Morris Graves' palace in exclusive Woodway Park. Guests, some in formal evening wear, arrived to find the driveway blocked by a trench; investigating on foot, they found a banquet table with a ten-day-old turkey feast being drenched by a garden sprinkler as dinner music and farm animal sounds played over speakers. With Graves and his cohorts refusing to answer the door, guests, amused and otherwise, responded by storming off, sketching the scene, or filching silverware from the table.[2][5] In September 1953, largely through the efforts of Seattle gallery owner Zoe Dusanne, Life magazine ran a major article on the "Mystic Painters of the Northwest", focusing on Graves, Mark Tobey, Kenneth Callahan, and Guy Anderson as the major figures of a perceived Northwest School of artists.[6] Ironically, by this time the four had for the most part fallen out over various personal, political, and artistic issues, and were barely on speaking terms with each other.[1] Graves' mid-career works were influenced by East Asian philosophy and mysticism, which he used as a way of approaching nature directly, avoiding theory. He adopted certain elements of Chinese and Japanese art, including the use of thin paper and ink drawing. He painted birds, pine trees, and waves. Works such as Blind Bird showed the influence of Mark Tobey, who was in turn inspired by Asian calligraphy. Graves switched from oils to gouaches, his birds became psychedelic, mystic, en route to transcendence. The paintings were bold, applied in a thick impasto with a palette knife, sometimes on coarse feed sacks.[7] In the 1950s, Graves returned to oils, but also painted in watercolor and tempera.

By 1954 Graves was feeling oppressed both by resurgent popularity and the encroachment of suburban development around his home. After spending several weeks in Japan, he rented Careladen to the poet Theodore Roethke and moved to Ireland. With companions Richard Svare and Dorothy Schumacher he lived in various parts of the country before settling on Woodton Manor, a rustic 18th century house near Dublin. In Ireland he created paintings known as the Hibernation series and became fascinated with the night sky. This led to Instruments for a New Navigation, a collection of precisely rendered bronze, glass, and stone sculptures inspired by the dawning Space Age. Finding no market for these unusual pieces, they were disassembled and not displayed again until 1999.[1][2] Graves returned to Seattle in 1964, living for several months in the so-called Pletscheff Mansion.[8]

In 1965 Graves purchased 380 acres of redwood forest property, around a five-acre lake, in Loleta, California, near Eureka. He hired architect Ibsen Nelsen to design a home which, after numerous technical and financial problems, was eventually constructed beside the lake. Graves would live on this property, which he called simply 'The Lake', for the remaining 35 years of his life. Although a sign posted at the entrance to the property read "No visitors today, tomorrow, or the day after", Graves' assistant Robert Yarber lived there with him much of the time, and he occasionally allowed visits by family members and old friends.[4] In his sixties, Graves began a new phase of minimalist paintings of floral arrangements, works with a simplicity intended as a statement about the nature of beauty. He unpacked the "Instruments of a New Navigation" sculptures and completed them. He continued working in his garden, tending his flowers and manicuring the landscape of The Lake.[9] Morris Graves died the morning of May 5, 2001 at his home in Loleta, hours after suffering a stroke.

The Morris Graves Museum of Art, located in the restored Carnegie library building in Eureka, California, bears his name and contains a small collection of his works and much of his personal collection of works by other artists.[3]

My published books: