Queer Places:

400 E 59th St, New York, NY 10022

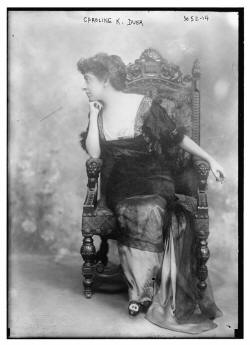

Caroline King Duer (February 27, 1865 - January 23, 1956) was the editor of the silverware and house furnishings section of Vogue magazine. She retired in 1937. She also was the author of many short stories and poems.

Friends of Sarah and

Eleanor Hewitt were privileged women, career pioneers, and philanthropists.

Elisabeth (“Bessy”) Marbury and

Elsie de Wolfe are perfect examples. Marbury pioneered a new profession as a talent agent for writers and performers, as well as a theater producer. Elsie de Wolfe “invented” the profession of interior decorating.

Anne Tracy Morgan,

Susan Dwight Bliss, and

Edith Malvina Wetmore were wealthy philanthropists, collectors, and donors to the Cooper Union Museum.

Caroline King Duer was a writer-poet-artist who became an editor at Vogue magazine. As a longtime friend of the Hewitts, Duer was a guest at all of the Hewitt residences, including Ringwood Manor, where she had her own regular room and was a prolific contributor to the estate’s colorful and often comical guestbooks.

Caroline King Duer (February 27, 1865 - January 23, 1956) was the editor of the silverware and house furnishings section of Vogue magazine. She retired in 1937. She also was the author of many short stories and poems.

Friends of Sarah and

Eleanor Hewitt were privileged women, career pioneers, and philanthropists.

Elisabeth (“Bessy”) Marbury and

Elsie de Wolfe are perfect examples. Marbury pioneered a new profession as a talent agent for writers and performers, as well as a theater producer. Elsie de Wolfe “invented” the profession of interior decorating.

Anne Tracy Morgan,

Susan Dwight Bliss, and

Edith Malvina Wetmore were wealthy philanthropists, collectors, and donors to the Cooper Union Museum.

Caroline King Duer was a writer-poet-artist who became an editor at Vogue magazine. As a longtime friend of the Hewitts, Duer was a guest at all of the Hewitt residences, including Ringwood Manor, where she had her own regular room and was a prolific contributor to the estate’s colorful and often comical guestbooks.

Caroline King Duer wrote an article for Vogue in 1948 titled “The Years Behind Me” that stated, “Having always longed to grow up, it appears to me now that I never have grown up. But I no longer care.” As a writer, poet, playwright, essayist, and Vogue editor, this flippant self-awareness characterized a sense of humor at once witty and insightful that pervaded her work, and coincidentally made her a perfect match for an amusing friendship with Sarah and Eleanor. Her mother, Elizabeth Wilson Meads, and her sister, Alice Duer Miller, were also writers, and the two sisters released a book of poetry together in 1896 (praised by the St. Louis Post as “Two Swell New York Sisters Have Been Wooing the Muses”).

Caroline King Duer was born into a wealthy family.[1] She was the daughter of James Gore King Duer[1][2] and Elizabeth Wilson Meads, the daughter of Orlando Meads of Albany, New York. In a Vogue article in 1948, titled “In the Non-Eccentric Nineties,” Duer reflected on her youth, as a child of the Gilded Age. She decried the harsh “burlesquing” of the Gilded Age by her contemporaries, who criticized the era as an extravagant whim and the people as wild eccentrics. Instead, she focused on the kind and generous personalities of those in her childhood social circles, specifically mentioning the warm hosting talents of Mrs. Hewitt and remembering that people often simply showed up at the Hewitt home for dinner: “I think the impromptu company was sometimes more fun, since those who arrived came, not because they were engaged to come, but because they had an urgent wish to be with the Hewitts at the particular time. There was an easy friendliness in that house missed in more ceremonious places.”

Duer modeled garments from the Hewitt sisters’ fashion collection in a 1931 article for Vogue titled “The Undying Quality of Style.”

Alice Duer Miller (left) and Caroline King Duer (right) with their mother, photographed in 1906. From the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

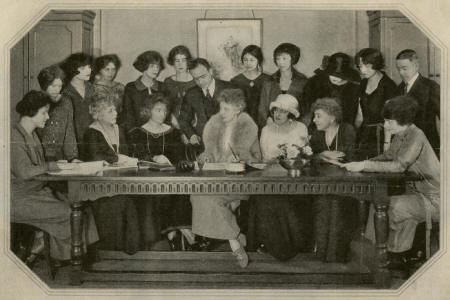

The editorial staff of Vogue, photographed in New York in 1923, picturing Caroline King Duer (seated, second from the right) and Carmel Snow (seated, third from the left) who would later become the famed editor of Harper’s Bazaar.

Shortly after Duer entered society around 1883, her grandfather died and she channeled her mourning into the study of nursing, later utilizing that training by working a year in Ris-Orangis, France, caring for wounded World War I soldiers. Duer was barely five feet tall and weighed little more than 100 pounds. In WWI she voluntered for service in a hospital in France and spent three years there. In 1918, she published Some Verses on the War: For the Benefit of the American Fund for French Wounded, a collection of poems on the need for patriotism. After World War I, she took a position writing and editing at Vogue, commenting on fashion, decorative arts, and etiquette (“I tried not to be humorous because Mr. [Condé] Nast always said people wouldn’t like humour mixed with manners, but I’m not sure I always succeeded.”).

While serving as an editor on Vogue she wrote two books, one of which was Vogues Book on Etiquette, the other was on fashions. After Pearl Harbor she again offered her services, this time as a volunteer hospital worker in New York. She was told that, at 75, she was too old for the tasks. Determined to aid in the war effort, Duer worked at the Travelers Aid canteen in Grand Central Terminal. There she served on the owl shift - from from mldnight to 4 a.m. - for a year. She supplemented this work with service two days a week at the Orthopedic Hospital where she wrote case histories, and at Memorial Hospital, where she worked in the operating room. Amidst all of this, she was most prolific in her poetry and short stories, writing continually for weekly magazines like Ainslee’s, Scribner’s, Putnam’s Monthly, and Harper’s.

She died at her home, 400 East Fiftyninth Street, New York at the age of 89.

My published books: