Queer Places:

St. Paul's Cathedral, London

Major-General

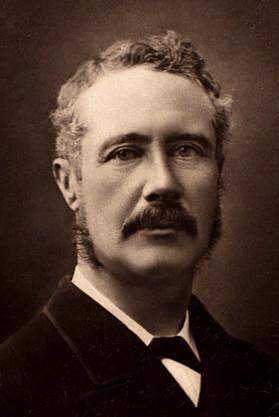

Charles George Gordon CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as

Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army

officer and administrator. He saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in

the British Army. However, he made his military reputation in China, where he

was placed in command of the "Ever Victorious Army," a force of Chinese

soldiers led by European officers. In the early 1860s, Gordon and his men were

instrumental in putting down the Taiping Rebellion, regularly defeating much

larger forces. For these accomplishments, he was given the nickname "Chinese

Gordon" and honours from both the Emperor of China and the British.

Major-General

Charles George Gordon CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as

Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army

officer and administrator. He saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in

the British Army. However, he made his military reputation in China, where he

was placed in command of the "Ever Victorious Army," a force of Chinese

soldiers led by European officers. In the early 1860s, Gordon and his men were

instrumental in putting down the Taiping Rebellion, regularly defeating much

larger forces. For these accomplishments, he was given the nickname "Chinese

Gordon" and honours from both the Emperor of China and the British.

He entered the service of the Khedive of Egypt in 1873 (with British government approval) and later became the Governor-General of the Sudan, where he did much to suppress revolts and the local slave trade. Exhausted, he resigned and returned to Europe in 1880.

A serious revolt then broke out in the Sudan, led by a Muslim religious leader and self-proclaimed Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. In early 1884 Gordon had been sent to Khartoum with instructions to secure the evacuation of loyal soldiers and civilians and to depart with them. In defiance of those instructions, after evacuating about 2,500 civilians he retained a smaller group of soldiers and non-military men. In the buildup to battle, the two leaders corresponded, each attempting to convert the other to his faith, but neither would accede.

Besieged by the Mahdi's forces, Gordon organised a citywide defence lasting almost a year that gained him the admiration of the British public, but not of the government, which had wished him not to become entrenched. Only when public pressure to act had become irresistible did the government, with reluctance, send a relief force. It arrived two days after the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed.

Gordon's charitable work for the boys of Gravesend led to later accusations in the 20th century that he was a homosexual.[69] The Dictionary of National Biography in what is clearly meant to be pun described Gordon as a great "boy lover".[66] Urban wrote:

It is possible that he had sexual feelings for these urchins, but there is no evidence that he ever acted upon them. We can only speculate that his increasing religious devotion may have been an outward manifestation of an internal struggle against sexual temptation.[64]

Gordon never married and is not known to have had a sexual or romantic relationship with anyone, claiming that his Army service and frequent travels to dangerous places made it impossible for him to marry as he was a "dead man walking" who could only hurt a potential wife as it was inevitable that he would die in battle.[70] Gordon's parents expected him to marry and were disappointed in his lifelong bachelorhood.[71] Urban wrote that the best evidence suggests Gordon was a latent homosexual whose sexual repression led him to funnelling his aggression into a military career with a special energy.[72] The British historian Denis Judd wrote about Gordon's sexuality:

Like two other great Imperial heroes of his time, Kitchener and Cecil Rhodes, Gordon was a celibate. What this almost certainly meant was that Gordon had unresolved homosexual inclinations which, like Kitchener, but unlike Rhodes, he kept savagely repressed. The repression of Gordon's sexual instincts helped to release a flood of celibate energy which drove him into weird beliefs, eccentric activities, and a sometimes misplaced confidence in his own judgement.[11]

The American historian Byron Farwell in his 1985 book Eminent Victorian Soldiers strongly implied that Gordon was gay, for instance writing of Gordon's "unwholesome" interest in the boys he took in to live with him at the Fort House and his fondness for the company of "handsome" young men.[73]

Gordon often said that he wished he had been born a eunuch, which would suggest that he wanted to annihilate all of his sexual desires, indeed his sexuality altogether.[74] Together with his sister Augusta, Gordon often prayed to be released from their "vile bodies" which their spirits were "imprisoned" in so that their souls might be joined with God.[75] Faught argued that no-one at the time suspected Gordon of having sexual relations with the legions of teenage boys living with him at the Fort House, and the claim he was secretly having sex with the boys of the Fort House was first made by Lytton Strachey in his book Eminent Victorians, which Faught commented may have said more about Strachey than it did about Gordon.[66]

Faught maintained that Gordon was a heterosexual whose Christian beliefs led him to maintain his virginity right up to his death as he believed that sexual intercourse was incompatible with his faith.[76] About the frequent references in Gordon's letters about his need to resist "temptation" and "subdue the flesh", Faught argued that it was women rather than men who were "tempting" him.[76] The South African minister Dr. Peter Hammond denied that Gordon was a homosexual, citing the numerous statements made by Gordon condemning homosexuality as an abomination, charging that the claim that Gordon was gay was a theory with no foundations in fact.[77] The British historian Paul Mersh suggested that Gordon was not gay, but rather his awkwardness with women was due to Asperger syndrome, which made it extremely difficult for him to express his feelings for women properly.[78]

St. Paul's Cathedral, London

The manner of Gordon's death is uncertain, but it was romanticised in a popular painting by George William Joy – General Gordon's Last Stand (1893, currently in the Leeds City Art Gallery), and again in the film Khartoum (1966) with Charlton Heston as Gordon. The most popular account of Gordon's death was that he put on his ceremonial gold-braided blue uniform of the Governor-General together with the Pasha's red fez and that he went out unarmed, except with his rattan cane, to be cut down by the Ansar.[11] This account was very popular with the British public as it contained much Christian imagery with Gordon as a Christ-like figure dying passively for the sins of all humanity.[11]

Gordon was apparently killed at the Governor-General's palace about an hour before dawn. The Mahdi had given strict orders to his three Khalifas not to kill Gordon.[213] The orders were not obeyed. Gordon's Sudanese servants later stated that Gordon for once did not go out armed only with his rattan cane, but also took with him a loaded revolver and his sword, and died in mortal combat fighting the Ansar.[214]

Gordon died on the steps of a stairway in the northwestern corner of the palace, where he and his personal bodyguard, Agha Khalil Orphali, had been firing at the enemy. Orphali was knocked unconscious and did not see Gordon die. When he woke up again that afternoon, he found Gordon's body covered with flies and the head cut off.[215]

A merchant, Bordeini Bey, glimpsed Gordon standing on the palace steps in a white uniform looking into the darkness. The best evidence suggests that Gordon went out to confront the enemy, gunned down several of the Ansar with his revolver and after running out of bullets, drew his sword only to be shot down.[11]

Reference is made to an 1889 account of the General surrendering his sword to a senior Mahdist officer, then being struck and subsequently speared in the side as he rolled down the staircase.[216] Rudolf Slatin, the Austrian governor of Darfur who had been taken prisoner by the Ansar wrote that three soldiers showed him Gordon's head at his tent before delivering it to the Mahdi.[217] When Gordon's head was unwrapped at the Mahdi's feet, he ordered the head transfixed between the branches of a tree ". . . where all who passed it could look in disdain, children could throw stones at it and the hawks of the desert could sweep and circle above."[218] His body was desecrated and thrown down a well.[218]

In the hours following Gordon's death an estimated 10,000 civilians and members of the garrison were killed in Khartoum.[218] The massacre was finally halted by orders of the Mahdi. Many of Gordon's papers were saved and collected by his two sisters, Helen Clark Gordon, who married Gordon's medical colleague in China, Dr. Moffit, and Mary Augusta and possibly his niece Augusta, who married Gerald Henry Blunt. Gordon's papers, as well as some of his grandfather's (Samuel Enderby III), were accepted by the British Library around 1937.[219]

The failure to rescue General Gordon's force in Sudan was a major blow to Prime Minister Gladstone's popularity. Queen Victoria sent him a telegram of rebuke which found its way into the press.[220] Victoria's telegram was not coded as usual which suggests she wanted it to appear in the press. Critics said Gladstone had neglected military affairs and had not acted promptly enough to save the besieged Gordon. Critics inverted his acronym, "G.O.M." (for "Grand Old Man"), to "M.O.G." (for "Murderer of Gordon"). Gladstone told the Cabinet that the public cared much about Gordon and nothing about the Sudan, so he ordered Wolseley home after learning of Gordon's death.[221] Wolseley, who had been led to believe that his expedition was the initial phase of the British conquest of the Sudan, was furious, and in a telegram to Queen Victoria contemptuously called Gladstone "...the tradesman who has become a politician".[221]

In 1885, Gordon achieved the martyrdom he had been seeking at Khartoum as the British press portrayed him as a saintly Christian hero and martyr who had died nobly resisting the Islamic onslaught of the Mahdi.[222] As late as 1901 on the anniversary of Gordon's death, The Times wrote in a leader (editorial) that Gordon was "that solitary figure holding aloft the flag of England in the face of the dark hordes of Islam".[201] Gordon's death caused a huge wave of national grief all over Britain with 13 March 1885 being set aside as a day of mourning for the "fallen hero of Khartoum".[220] In a sermon, the Bishop of Chichester stated: "Nations who envied our greatness rejoiced now at our weakness and our inability to protect our trusted servant. Scorn and reproach were cast upon us, and would we plead that it was undeserved? No; the conscience of the nation felt that a strain rested upon it".[220]

Baring – who deeply disliked Gordon – wrote that because of the "national hysteria" caused by Gordon's death, saying anything critical about him at present would be equal to questioning Christianity.[220] Stones were thrown at the windows at 10 Downing Street as Gladstone was denounced as the "Murderer of Gordon", the Judas figure who betrayed the Christ figure Gordon.[11] The wave of mourning was not just confined to Britain. In New York, Paris and Berlin, pictures of Gordon appeared in shop windows with black lining as all over the West the fallen general was seen as a Christ-like man who sacrificed himself resisting the advance of Islam.[11]

Despite the popular demand to "avenge Gordon", the Conservative government that came into office after the 1885 election did nothing of the sort. The Sudan was judged to be not worth the huge financial costs it would have taken to conquer it, the same conclusion that the Liberals had reached.[11] After Khartoum, the Mahdi established his Islamic state which restored slavery and imposed a very harsh rule that according to one estimate caused the deaths of 8 million people between 1885–1898.[223] In 1887, the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition under Henry Morton Stanley set out to rescue Dr. Emin Pasha, still holding out in Equatoria against the Ansar. Many have seen the attempt to save Emin Pasha, a German doctor-biologist-botanist who had converted from Judaism first to Lutheranism and then (possibly) to Islam, and who had not been particularly famous in Europe until then, as a consolation prize for Gordon.[224]

Egypt had been in the French sphere of influence until 1882 when the British had occupied Egypt. In March 1896 a French force under the command of Jean-Baptiste Marchand left Dakar with the intention of marching across the Sahara with the aim of destroying the Mahdiyah state. The French hoped that conquering the Sudan would allow them to lever the British out of Egypt, and thus restore Egypt to the French sphere of influence.[11]

To block the French, a British force under Herbert Kitchener was sent to destroy the Mahdiyah state and annihilated the Ansar at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898. It was thus imperial rivalry with the French, not a desire to "avenge Gordon" that led the British to end the Mahdiyah state in 1898.[11] However the British public and Kitchener himself saw the expedition as one to "avenge Gordon". As the Mahdi was long dead, Kitchener had to content himself with blowing up the Mahdi's tomb as revenge for Gordon.[225] After the Battle of Omdurman, Kitchener opened a letter from the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, and for the first time learned the real purpose of the expedition had been to keep the French out of the Sudan and that "avenging Gordon" was merely a pretext.[226]

News of Gordon's death led to an "unprecedented wave of public grief across Britain." A memorial service, conducted by the Bishop of Newcastle, was held at St. Paul's Cathedral on 14 March. The Lord Mayor of London opened a public subscription to raise funds for a permanent memorial to Gordon; this eventually materialised as the Gordon Boys Home, now Gordon's School, in West End, Woking.[227][228]

My published books: