Queer Places:

80 Rodney St, Liverpool L1, UK

Sutton Court, Stowey, Pensford, Bristol BS39 4DN, UK

University Of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2, UK

Stowey House, Windmill Dr, London SW4 9DE, UK

69 Lancaster Gate, London W2, UK

51 Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1H, UK

6 Belsize Park Gardens, London NW3, UK

67 Belsize Park Gardens, London NW3 4JN, UK

The Mill, Tidmarsh, Reading RG8 8ER, UK

Ham Spray House, Marlborough SN8 3QZ, UK

St Andrew, Tunbridge Cl, Chew Magna, Bristol BS40 8SU, UK

Giles Lytton Strachey

[1]

(1 March 1880 – 21 January 1932) was a British writer and critic. He was part

of the Cambridge Apostles.

He appears as Risley in E.M.

Forster's novel Maurice (published posthumously in 1971). The Apes

of God (1930) by Wyndham Lewis contains a satirical portrait of him as

Matthew Plunkett. Wyndham Lewis portrayed him as Cedric Furber in

Self-Condemned (1954). Leonard Woolf

modelled one of the "epicures" in his novel The Wise Virgins (1914) on

him. The character of Neville in

Virginia Woolf's The Waves

(1931) is based in part on Lytton Strachey.

Giles Lytton Strachey

[1]

(1 March 1880 – 21 January 1932) was a British writer and critic. He was part

of the Cambridge Apostles.

He appears as Risley in E.M.

Forster's novel Maurice (published posthumously in 1971). The Apes

of God (1930) by Wyndham Lewis contains a satirical portrait of him as

Matthew Plunkett. Wyndham Lewis portrayed him as Cedric Furber in

Self-Condemned (1954). Leonard Woolf

modelled one of the "epicures" in his novel The Wise Virgins (1914) on

him. The character of Neville in

Virginia Woolf's The Waves

(1931) is based in part on Lytton Strachey.

A founding member of the

Bloomsbury Group and author of

Eminent Victorians, he is best known for establishing a new form of

biography in which

psychological insight and sympathy are combined with irreverence and wit.

His biography Queen Victoria (1921) was awarded the

James Tait Black Memorial Prize.

Strachey was born on 1 March 1880 at Stowey House, Clapham Common, London,

the fifth son and eleventh child of Lieutenant General Sir Richard Strachey,

an officer in the British colonial armed forces, and his second wife, the

former Jane Grant, who became a leading supporter of the women's suffrage

movement. He was named "Giles Lytton" after an early sixteenth-century Gyles

Strachey and the first Earl of Lytton, who had been a friend of Richard

Strachey's when he was Viceroy of India in the late 1870s. The Earl of Lytton

was also Lytton Strachey's godfather.[2]

The Stracheys had thirteen children in total, ten of whom survived to

adulthood, including Lytton's sister

Dorothy Strachey and youngest brother, the psychoanalyst,

James Strachey.

Lytton Strachey was part of the

Cambridge Apostles like John

Maynard Keynes. The

relation between the two leaders within the Apostles was always an ambivalent

one, riven by rivalry over their loves. There was the charming

George Duckworth: Strachey discovered by accident that Keynes was also after him.

There was abitter tussle as to who should sponsor him for the Apostolic

fellowship; Keynes, being more ruthless, won. We learn that "for two months

following the election of Duckworth, Lytton was filled with an almost demented

hatred of Keynes." He even "launched an extraordinary onslaught upon Keynes

before the assembled Apostles." Shockingly unethical, according to the gospel

of the Venerable Moore. Shortly Strachey transferred his affections to

Bernard Winthrop Swithinbank, and Duckworth transferred his to the irresistible

Duncan Grant. So Strachey was one, or possible two, up.

Then Lytton became ensnared by the beauty of Duncan. The next test for the

Apostle Moore's gospel was when Lytton found out - again by accident, for he

hadn't much psychological perception - that the predatory Keynes had captured

Duncan from him, and that Duncan returned his love. Accepting the mutuality of

this esteem, Lytton decided to apply Old Moore's almanac and strike the note

of magnanimity: "I don't hate you and, if you were here now, I should probably

kiss you, except that Duncan would be jealous, which would never do!" Keynes

wrote back in similar mood: "Your letter made me cry."

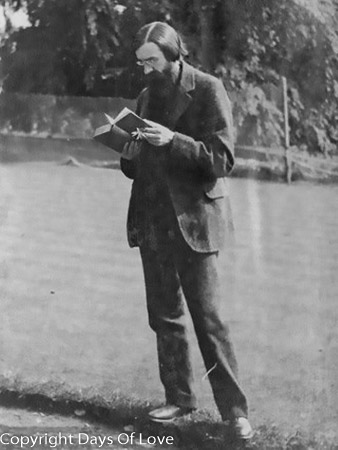

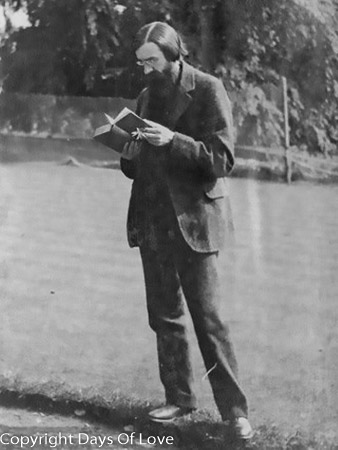

Lytton Strachey by Dora Carrington, 1916

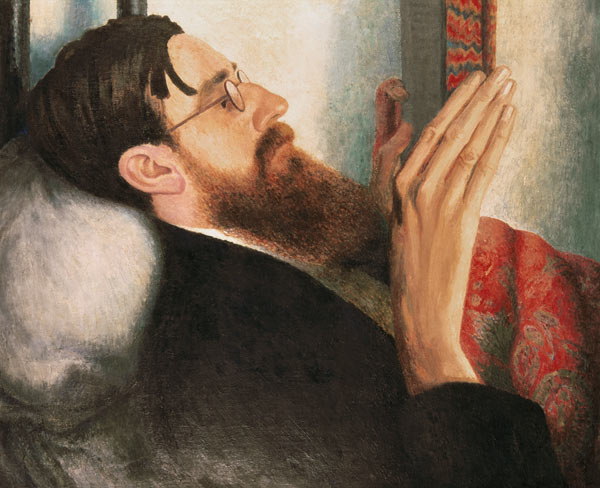

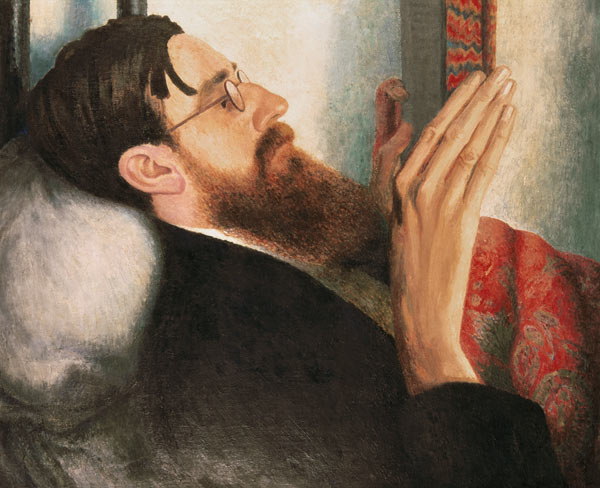

Lytton Strachey by Henry Lamb

Lytton Strachey

Duncan Grant (1885–1978)

Charleston

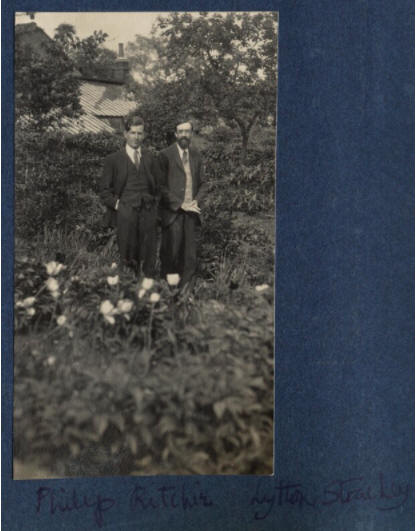

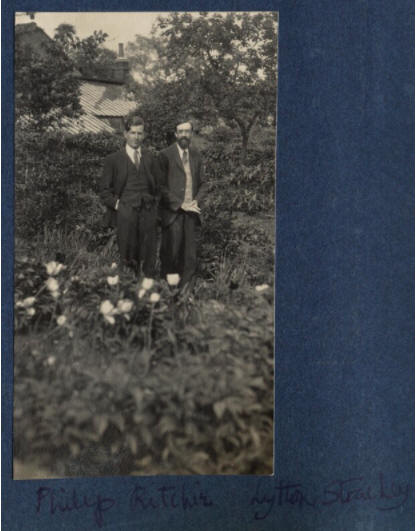

Philip Charles Thomson Ritchie; Lytton Strachey

by Lady Ottoline Morrell

vintage snapshot print, 1924

3 7/8 in. x 2 1/8 in. (97 mm x 54 mm) image size

Purchased with help from the Friends of the National Libraries and the Dame Helen Gardner Bequest, 2003

Photographs Collection

NPG Ax141563

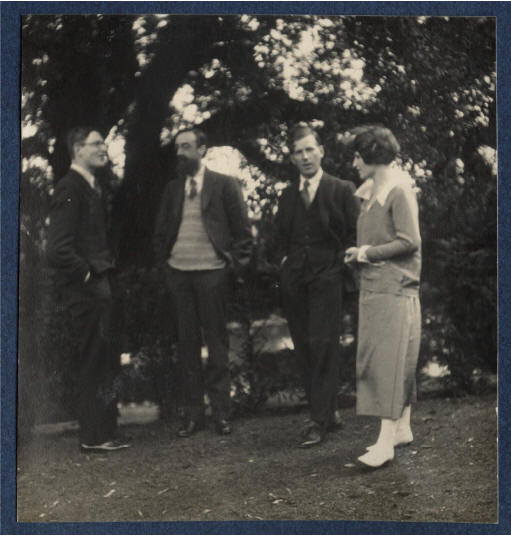

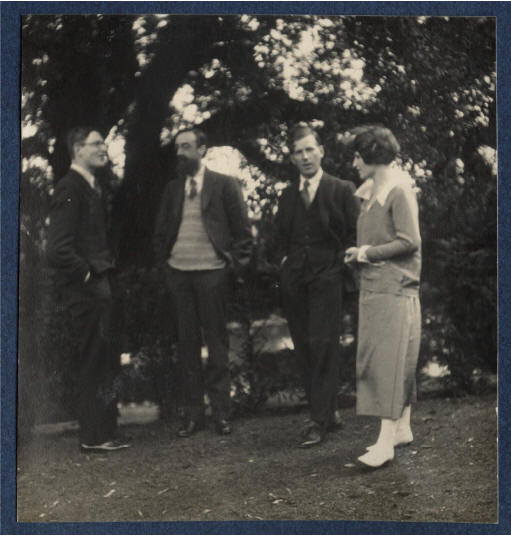

William David Hogarth; Lytton Strachey; Philip Charles Thomson Ritchie; Julian Vinogradoff (née Morrell)

by Lady Ottoline Morrell

vintage snapshot print, 1924

3 1/8 in. x 2 7/8 in. (78 mm x 74 mm) image size

Purchased with help from the Friends of the National Libraries and the Dame Helen Gardner Bequest, 2003

Photographs Collection

NPG Ax141562a

_Sprott;_Lytton_Strachey,_June_1926.jpg)

Lady Ottoline Morrell (1873–1938), vintage snapshot print/NPG Ax142600. Dora Carrington; Stephen Tomlin; Walter John Herbert ('Sebastian') Sprott; Lytton Strachey, June 1926

St Andrew, Chew Magna

At a military tribunal concerning his application for Conscientious

Objector status, in 1916, Lytton Strachey was asked what he would do if he saw

a German soldier raping his sister. He replied, ‘I would try to get between

them.’

Though Strachey spoke openly about his homosexuality with his Bloomsbury

friends, and had relationships with a variety of men including

Ralph Partridge, details of Strachey's sexuality were not widely known

until the publication of

a biography by

Michael Holroyd in the late 1960s.

Dora Carrington, the painter, and Strachey participated in a lifelong open

relationship, and eventually established a permanent home together at Ham

Spray House, where Carrington would paint and Strachey would educate her in

literature.[21]

In 1921 Carrington agreed to marry Ralph Partridge, not for love but to secure

their three-way relationship that consisted of herself, Strachey and

Partridge. Partridge eventually formed a relationship with Frances Marshall,

another Bloomsbury member.[22]

Shortly after Strachey died, Carrington committed suicide. Partridge married

Frances Marshall in 1933. Strachey himself had been much more interested

sexually in Partridge, as well as in various other young men,[23]

including a secret

sadomasochistic relationship with

Roger Senhouse (later the head of the publishing house

Secker & Warburg).[24]

Strachey's letters, edited by Paul Levy, were published in 2005.[25]

W. Somerset Maugham

first met Alan Searle in 1928, when

Searle was "a very youthful looking twenty-three, a working class boy from

Bermondsey, the son of a Dutch tailor and cockney mother". He was the lover of several famous older men, including Lytton Strachey,

who called Searle his "Bronzino boy".

In 1930, after dining with various homosexual men, including

E.M. Forster and

Lytton Strachey, whose conversation

strayed on to the topic of attractive youths,

Virginia Woolf said she had

received ‘a tinkling, private, giggling impression. As if I had gone into a

men’s urinal.’ Of

Eddy Sackville-West she said, quite simply, ‘I can’t take Buggerage

seriously.’ Hermione Lee, her biographer, comments, as follows: ‘Like

Simone de Beauvoir twenty years later … the feminist in her deplored the fact that

gay men seemed to want to be women. And she must also have felt that

homosexuality was, for the next generation of writers, an exclusive exclusive

passport for literary success.’

The private letters of

Lytton Strachey

reveal that Roger Senhouse was his last lover, with whom he had a secretly

sado-masochistic relationship in the early 1930s.[1]

According to a letter, Lytton "anxiously hovered, blowing hot and cold over

Philip Ritchie,

and alternately cold and hot over his companion, Roger Senhouse."

Strachey died of stomach cancer on 21 January 1932, aged 51. It is reported

that his final words were: "If this is dying, then I don't think much of it."

[20]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lytton_Strachey

- Woods, Gregory. Homintern . Yale University Press. Edizione del

Kindle.

- Homosexuals in History, A Study of Ambivalence in Society, Literature

and the Arts, by A.L. Rowse, 1977

Giles Lytton Strachey

[1]

(1 March 1880 – 21 January 1932) was a British writer and critic. He was part

of the Cambridge Apostles.

He appears as Risley in E.M.

Forster's novel Maurice (published posthumously in 1971). The Apes

of God (1930) by Wyndham Lewis contains a satirical portrait of him as

Matthew Plunkett. Wyndham Lewis portrayed him as Cedric Furber in

Self-Condemned (1954). Leonard Woolf

modelled one of the "epicures" in his novel The Wise Virgins (1914) on

him. The character of Neville in

Virginia Woolf's The Waves

(1931) is based in part on Lytton Strachey.

Giles Lytton Strachey

[1]

(1 March 1880 – 21 January 1932) was a British writer and critic. He was part

of the Cambridge Apostles.

He appears as Risley in E.M.

Forster's novel Maurice (published posthumously in 1971). The Apes

of God (1930) by Wyndham Lewis contains a satirical portrait of him as

Matthew Plunkett. Wyndham Lewis portrayed him as Cedric Furber in

Self-Condemned (1954). Leonard Woolf

modelled one of the "epicures" in his novel The Wise Virgins (1914) on

him. The character of Neville in

Virginia Woolf's The Waves

(1931) is based in part on Lytton Strachey.

_Sprott;_Lytton_Strachey,_June_1926.jpg)