Queer Places:

Charleton House, Colinsburgh, Leven KY9 1HG, Regno Unito

Villa Il Palmerino, Via del Palmerino, 10, 50137 Firenze FI, Italia

Kilconquhar Parish Church, Leven KY9 1JZ, Regno Unito

Clementina

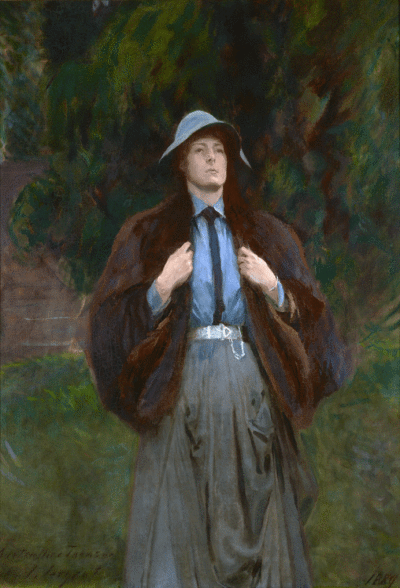

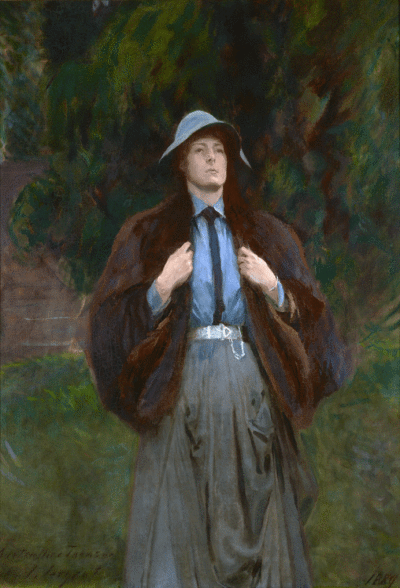

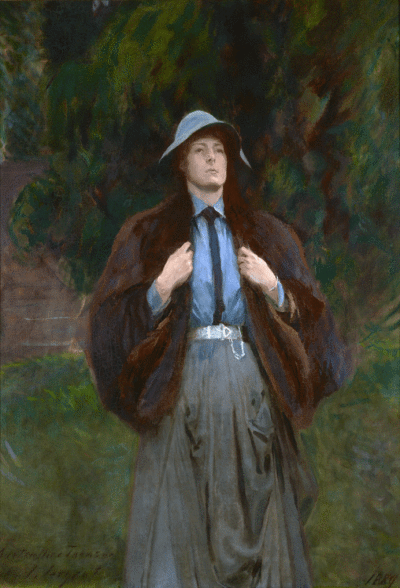

"Kit" Caroline Anstruther-Thomson (1857–1921) was a Scottish author and art

theorist. She was known for writing and lecturing on experimental aesthetics

during the Victorian era.

Her collaboration with Vernon

Lee in the 1890s inspired Lee's growing interests in the psychological

aspect of aesthetics later in her career.

Vernon

Lee lived most of the time in Italy, where she was much given to visiting

churches, museums and galleries; doing this in the 1890s with her lover, the

painter Clementina

Anstruther-Thomson, she decided to undertake a study of what happens to

the human body when the mind is occupied with the vista of an aesthetic

object: a building, a decorative jar, a painting. Anstruther-Thomson kept a

diary in which she recorded her reactions, how looking at art made her feel.

She noted her respiration and heart rate, balance, muscular tension, the

manner and speed with which her right and left lungs filled with air. For

example, looking at the Gothic-Renaissance façade of Santa Maria Novella in

Florence one day, she observed that her balance changed and her breathing

deepened. The composer Ethel Smyth, who had

also had a relationship with Lee, made snide comments about what Lee and

Anstruther-Thompson were doing, ‘experimenting’ in art galleries.

Clementina

"Kit" Caroline Anstruther-Thomson (1857–1921) was a Scottish author and art

theorist. She was known for writing and lecturing on experimental aesthetics

during the Victorian era.

Her collaboration with Vernon

Lee in the 1890s inspired Lee's growing interests in the psychological

aspect of aesthetics later in her career.

Vernon

Lee lived most of the time in Italy, where she was much given to visiting

churches, museums and galleries; doing this in the 1890s with her lover, the

painter Clementina

Anstruther-Thomson, she decided to undertake a study of what happens to

the human body when the mind is occupied with the vista of an aesthetic

object: a building, a decorative jar, a painting. Anstruther-Thomson kept a

diary in which she recorded her reactions, how looking at art made her feel.

She noted her respiration and heart rate, balance, muscular tension, the

manner and speed with which her right and left lungs filled with air. For

example, looking at the Gothic-Renaissance façade of Santa Maria Novella in

Florence one day, she observed that her balance changed and her breathing

deepened. The composer Ethel Smyth, who had

also had a relationship with Lee, made snide comments about what Lee and

Anstruther-Thompson were doing, ‘experimenting’ in art galleries.

Anstruther-Thomson was born to John Anstruther-Thomson of Charleton and

Carntyne, and Caroline Maria Agnes Robina Gray in an aristocratic family. Her

grandfather, also John Anstruther-Thomson, was a career officer in the British

Territorial Army.

The aesthetic movement in the United Kingdom began in the 1860s during the

Victorian period.[4]

In Victorian literature, writers of the aesthetic movement focused on the

sensual aspect of aesthetics. Anstruther-Thomson in particular was keen on

experiencing art physically with her body.

In one of the lectures titled "What Patterns Do to Us" given by

Anstruther-Thomson, she encouraged the audience to engage with a patterned

vase and "feel its effect on their bodies".

Vernon Lee was already familiar with Anstruther-Thomson prior to meeting

her. Contemporary writers have described Anstruther-Thomson as having the

physique that resembles the ideals from ancient Greek sculpture, and Lee

frequently described her obsession with Anstruther-Thomson's body in her

writings.

When Lee observed art with Anstruther-Thomson, her aesthetic experience was

based on "lesbian desire" of Anstruther-Thomson's body that embodied Greek

ideals.

by John Singer Sargent

Anstruther-Thomson first met Vernon Lee in 1888, and for the next twelve

years the two women openly lived together, as "lovers, friends, and

co-authors".

Living as expatriates in Italy, they often travelled back and forth to

Britain. In their time together, they took aesthetics experiments and recorded

their findings. Throughout the 1890s, Anstruther-Thomson and Lee visited many

museums across continental Europe and observed many art works. In their

observation, they recorded in writing on how their body responded to art

works.

In 1897, they published the combined findings in the article "Beauty and

Ugliness", which investigates the physiology of aesthetics. Their research was

based on the James–Lange theory of how the human body responds to stimulation

and triggers emotion.

Many of the findings, however, were not taken seriously as both their

professional and romantic relationship was "attacked"

by their contemporaries, receiving "severe criticisms" from friends.

.JPG)

Villa Il Palmerino

After the publication of "Beauty and Ugliness", Anstruther-Thomson

gradually drifted away from Lee, and eventually broke off the relationship in

1898.

They remained close friends until the death of Anstruther-Thomson in 1921.

Later in her life, Anstruther-Thomson worked closely with the Girl Guides of

America. Many of the earlier leaders were single women, and some were lesbian

as well, for whom Guiding provided a safe refuge.

Anstruther-Thomson was both an organizer and trainer, and held the position of

County Commissioner until her death.

She was buried with her family in Kilconquhar Parish Churchyard, Kilconquhar.

Her writings on aesthetics were collected and published posthumously by Lee

in Art and Man in 1924, with an introduction, also by Lee, that

describes their collaboration in experiencing art.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clementina_Anstruther-Thomson

- Oakley, Ann. Women, Peace and Welfare . Policy Press. Edizione del

Kindle.

Clementina

"Kit" Caroline Anstruther-Thomson (1857–1921) was a Scottish author and art

theorist. She was known for writing and lecturing on experimental aesthetics

during the Victorian era.[1]

Her collaboration with Vernon

Lee in the 1890s inspired Lee's growing interests in the psychological

aspect of aesthetics later in her career.[2]

Vernon

Lee lived most of the time in Italy, where she was much given to visiting

churches, museums and galleries; doing this in the 1890s with her lover, the

painter Clementina

Anstruther-Thomson, she decided to undertake a study of what happens to

the human body when the mind is occupied with the vista of an aesthetic

object: a building, a decorative jar, a painting. Anstruther-Thomson kept a

diary in which she recorded her reactions, how looking at art made her feel.

She noted her respiration and heart rate, balance, muscular tension, the

manner and speed with which her right and left lungs filled with air. For

example, looking at the Gothic-Renaissance façade of Santa Maria Novella in

Florence one day, she observed that her balance changed and her breathing

deepened. The composer Ethel Smyth, who had

also had a relationship with Lee, made snide comments about what Lee and

Anstruther-Thompson were doing, ‘experimenting’ in art galleries.

Clementina

"Kit" Caroline Anstruther-Thomson (1857–1921) was a Scottish author and art

theorist. She was known for writing and lecturing on experimental aesthetics

during the Victorian era.[1]

Her collaboration with Vernon

Lee in the 1890s inspired Lee's growing interests in the psychological

aspect of aesthetics later in her career.[2]

Vernon

Lee lived most of the time in Italy, where she was much given to visiting

churches, museums and galleries; doing this in the 1890s with her lover, the

painter Clementina

Anstruther-Thomson, she decided to undertake a study of what happens to

the human body when the mind is occupied with the vista of an aesthetic

object: a building, a decorative jar, a painting. Anstruther-Thomson kept a

diary in which she recorded her reactions, how looking at art made her feel.

She noted her respiration and heart rate, balance, muscular tension, the

manner and speed with which her right and left lungs filled with air. For

example, looking at the Gothic-Renaissance façade of Santa Maria Novella in

Florence one day, she observed that her balance changed and her breathing

deepened. The composer Ethel Smyth, who had

also had a relationship with Lee, made snide comments about what Lee and

Anstruther-Thompson were doing, ‘experimenting’ in art galleries..JPG)