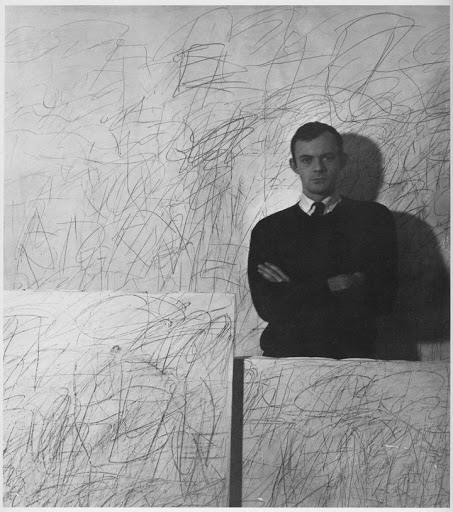

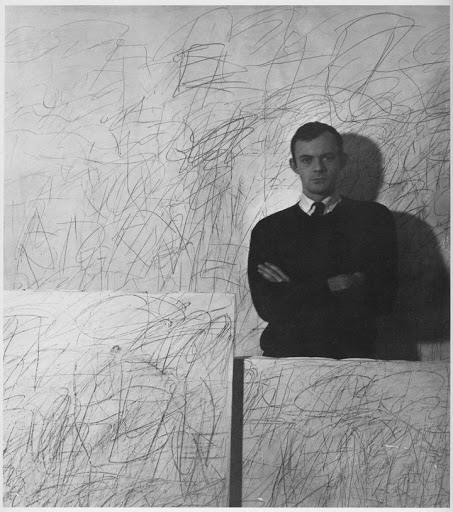

Edwin Parker "Cy" Twombly Jr. (April 25, 1928 – July 5, 2011)[1]

was an American painter, sculptor and photographer. He belonged to the

generation of

Robert Rauschenberg and

Jasper Johns but chose to live in Italy after 1957.

Edwin Parker "Cy" Twombly Jr. (April 25, 1928 – July 5, 2011)[1]

was an American painter, sculptor and photographer. He belonged to the

generation of

Robert Rauschenberg and

Jasper Johns but chose to live in Italy after 1957.Partner Robert Rauschenberg, Nicola Del Roscio

Queer Places:

Tufts School of the Museum of Fine Arts, 230 Fenway, Boston, MA 02115, Stati Uniti

National Academy Museum & School, 1083 5th Ave, New York, NY 10128, Stati Uniti

Black Mountain College, Black Mountain, NC 28711, Stati Uniti

Washington and Lee University, 204 W Washington St, Lexington, VA 24450, Stati Uniti

The Art Students League of New York, 215 W 57th St, New York, NY 10019, Stati Uniti

356 Bowery, New York, NY 10012, Stati Uniti

Via di Monserrato, 49, 00186 Roma RM, Italia

Fondazione Nicola Del Roscio, Via S. Maria Ausiliatrice, 04024 Gaeta LT, Italia

Bassano In Teverina, 01030 Bassano In Teverina VT, Italia

Cy Twombly Foundation, 19 East 82nd Street, 10028, NYC, NY, USA

Edwin Parker "Cy" Twombly Jr. (April 25, 1928 – July 5, 2011)[1]

was an American painter, sculptor and photographer. He belonged to the

generation of

Robert Rauschenberg and

Jasper Johns but chose to live in Italy after 1957.

Edwin Parker "Cy" Twombly Jr. (April 25, 1928 – July 5, 2011)[1]

was an American painter, sculptor and photographer. He belonged to the

generation of

Robert Rauschenberg and

Jasper Johns but chose to live in Italy after 1957.

His paintings are predominantly large-scale, freely-scribbled, calligraphic and graffiti-like works on solid fields of mostly gray, tan, or off-white colors. Many of his works are in the permanent collections of most of the museums of modern art around the world, including the Menil Collection in Houston, the Tate Modern in London and the New York's Museum of Modern Art. He was also commissioned for the ceiling of a room of the Musée du Louvre in Paris.

Many of his later paintings and works on paper shifted toward "romantic symbolism", and their titles can be interpreted visually through shapes and forms and words. Twombly often quoted the poets as Stéphane Mallarmé, Rainer Maria Rilke and John Keats, as well as many classical myths and allegories in his works. Examples of this are his Apollo and The Artist and a series of eight drawings consisting solely of inscriptions of the word "Virgil". In a 1994 retrospective, curator Kirk Varnedoe described Twombly's work as "influential among artists, discomfiting to many critics and truculently difficult not just for a broad public, but for sophisticated initiates of postwar art as well."[2] After acquiring Twombly's Three Studies from the Temeraire (1998–99), the Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales said, "Sometimes people need a little bit of help in recognising a great work of art that might be a bit unfamiliar."[3] Twombly is said to have influenced younger artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Anselm Kiefer, Francesco Clemente, and Julian Schnabel.[4]

The Broad, Los Angeles

Twombly was born in Lexington, Virginia, on April 25, 1928. Twombly's father, also nicknamed "Cy", pitched for the Chicago White Sox.[5] They were both nicknamed after the baseball great Cy Young who pitched for, among others, the Cardinals, Red Sox, Indians, and Braves.

At age 12, Twombly began to take private art lessons with the Catalan modern master Pierre Daura.[6] After graduating from Lexington High School in 1946, Twombly attended Darlington School in Rome, Georgia, and studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1948–49), and at Washington and Lee University (1949–50) in Lexington, Virginia. On a tuition scholarship from 1950 to 1951, he studied at the Art Students League of New York, where he met Robert Rauschenberg with whom he had a relationship.[7] Rauschenberg encouraged him to attend Black Mountain College near Asheville, North Carolina. At Black Mountain in 1951 and 1952 he studied with Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell and Ben Shahn, and met John Cage. The poet and rector of the College Charles Olson had a great influence on him.

Arranged by Motherwell, Twombly's first solo exhibition was organized by the Samuel M. Kootz Gallery in New York in 1951. At this time his work was influenced by Kline's black-and-white gestural expressionism, as well as Paul Klee's imagery. In 1952, Twombly received a grant from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts which enabled him to travel to North Africa, Spain, Italy, and France. He spent this journey in Africa and Europe with Robert Rauschenberg. In 1954, he served in the U.S. Army as a cryptographer in Washington, D.C. and would frequently travel to New York during periods of leave. From 1955 through 1956, he taught at the Southern Seminary and Junior College in Buena Vista, Virginia, currently known as Southern Virginia University; during the summer vacations, Twombly would travel to New York to paint in his Williams Street apartment.[8]

In 1957, Twombly moved to Rome, where he met the Italian artist Tatiana Franchetti – sister of his patron Baron Giorgio Franchetti. They were married at City Hall in New York in 1959[9] and then bought a palazzo on the Via di Monserrato in Rome. In addition, they had a 17th-century villa in Bassano in Teverina, north of Rome.[10] They had a son, Cyrus Alessandro Twombly (born 1959), who is also a painter and lives in Rome.

In 1964, Twombly met Nicola Del Roscio of Gaeta, who became his longtime companion.[10][11] Twombly bought a house and rented a studio in Gaeta in the early 1990s.[10] Twombly and Tatiana, who died in 2010, never divorced and remained friends.[10]

At the exhibition Robert Rauschenberg: Combines at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (December 2005–April 2006), which examined Rauschenberg’s groundbreaking painted sculptural objects, the signage was particularly misleading. A history of the artist’s work and life was mounted on the entry wall to the exhibit, which most viewers read intently (some were even taking notes on my visit). The following text appeared toward the end of the statement: In 1949 Rauschenberg and [Susan] Weil moved to New York. They married the following year, and their son, Christopher, now a photographer, was born in 1951. That spring Rauschenberg had his first solo exhibition, at Betty Parsons Gallery in New York, and met the composer John Cage and the dancer-choreographer Merce Cunningham. Their friendship solidified in summer 1952 at Black Mountain, where they were teaching and Cy Twombly was a student. Rauschenberg and Twombly traveled to Europe, chiefly Italy, for a year, and in 1953, back in New York, they had concurrent exhibitions at the Stable Gallery. Looking at this text, we can see how the institution attempted to place Rauschenberg in the guise of a different-sex lover. If Rauschenberg’s sexuality is unimportant, why inform the public that he was married and had a child? Obviously, his sexuality was important to the exhibitors, and by extension, then, information regarding the artist’s same-sex activities should have been considered significant as well. Rauschenberg and Twombly traveled to Europe as lovers, a fact that is widely known and documented; the trip was the equivalent of a honeymoon. The sign did not explain why Rauschenberg would leave his baby and its mother to go off for a year with a man. Nor did it explain that Cage and Cunningham were lovers and remained so for the rest of Cage’s life. These facts are widely documented. We are therefore led to wonder why Rauschenberg’s same-sex lovers were given a lower hierarchical status, in fact deleted from the institutional narrative. Only in the huge accompanying catalogue was there any mention of Rauschenberg’s same-sex activities, and then they were briefly glossed over: “During the second half of the 1950s, Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg were neighbors, friends, lovers, and, most significantly, artists developing work for which they would ultimately become well known.” While readers of the text might be grateful for this small acknowledgement, nowhere in the exhibition was this information available. It was refreshing to see the relationship between Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns finally acknowledged, even if in such a slight way, yet many visitors would have missed the passage as they scanned the huge text on display in the shop. Few actually purchased the books, because they were expensive ($45 paper, $75 cloth), leaving the vast majority of viewers without this historical information, while the actual exhibit continually informed them of the artist’s heterosexual activities. Nor were they informed of how works like Bed (1955) included in the exhibition directly referenced the artist’s sexual relationship with Johns. Rauschenberg’s art should have been at the center of the discussion, but this could not occur because the museum mostly denied that the art was often made for and about his male same-sex lovers, and not for his wife, whom he divorced within 16 months of marriage, nor his child.

The 2008 Cy Twombly Cycles and Seasons exhibition at Tate Modern in London presented viewers with distorted signage. It referred to the trip Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg took as one between friends and in no way acknowledged the sexual side of their relationship for that extended journey. In the accompanying catalog, the trip was not described as a honeymoon. The chronology did state that “Rauschenberg, who at the time is separating from his wife Susan Weil, decides to join him.” This part of the chronology was illustrated with two intimate photographs taken of Twombly by Rauschenberg, and a third work, a photomontage by Rauschenberg called Cy + Bob – Venice (1952), in which the men are seen side by side under the stallions at St. Mark’s. At no time did the text allude to the sexual nature of the friendship or the romantic status of the trip. On the other hand, it did call Twombly’s visit to Cuba with Tatiana Franchetti a “honeymoon trip” when it documented their marriage in 1959, long after Rauschenberg had left Twombly for Jasper Johns. If biographical sexual information were of no importance, the reader would not be told by the institution that the artist married a woman. That the Tate did not place Twombly’s relationship with Rauschenberg on equal footing, actively eliding information that was already in the public domain, was yet another example of the open prejudice faced by same-sex lovers and the whole LGBT population. It is doubly sad that this happened at one of the world’s leading art institutions, one funded by the public, and that it happened as recently as 2008.

In 2011, Twombly died in Rome after being hospitalized for several days; he had had cancer for many years.[12] A plaque in Santa Maria in Vallicella commemorates him.[13]

Twombly's will, written under U.S. law, allocated the bulk of the artist's art and cash to the Cy Twombly Foundation. The foundation now controls much of Twombly's work. It has reported $70 million in assets in 2011, and $1.5 billion in the following two years.[40][41] In 2012 it purchased a 25-foot-wide Beaux Arts mansion on 19 E 82nd St, Upper East Side Manhattan, planning to open an education center and a small museum.[42][43] There is an additional foundation office on the Gaeta property.[10] The four board members were divided in a lawsuit, settled in March 2014.[44]

My published books: