BURIED TOGETHER

Partner

Elsie

Inglis, Louisa

Garrett Anderson

Queer Places:

(1912) 85 Campden Hill Court, London W

(1921)

60 Bedford Gardens, Campden Hill, London W

(1923)

Pauls End (now Gatemoor Grange), Pauls Hill, Penn, High Wycombe HP10 8NZ, UK

Women's Hospital for Children, 688 Harrow Rd, London W10, UK

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

Holy Trinity Churchyard

Penn, Chiltern District, Buckinghamshire, England

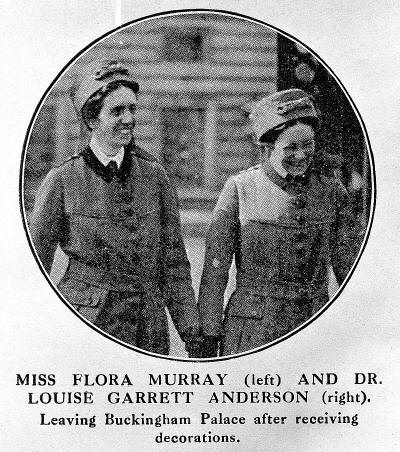

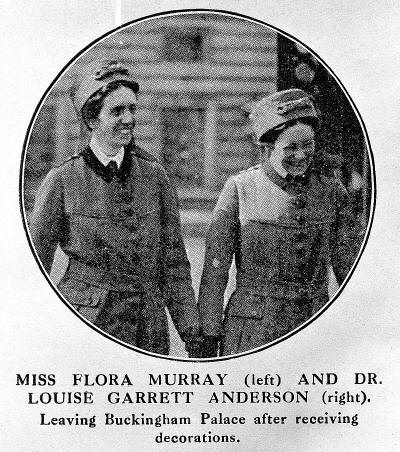

Flora

Murray, CBE (8 May 1869 – 28 July 1923)[1] was

a Scottish medical pioneer, and a member of the Women's Social and Political

Union suffragettes.[2] From

1914 to the end of her life, she lived with her partner and doctor Louisa

Garrett Anderson.[3]

Before that, Murray lived for a number of years with Dr

Elsie

Inglis, founder of the

Scottish Women’s Hospitals, in Edinburgh. In May 1915, Drs

Louisa Garrett Anderson

and Flora Murray founded the Endell

Street military hospital in London and from 1916 onwards, women doctors began

to work in hospitals on the front line in Malta, Salonika, Egypt, India, East

Africa and Palestine.

Flora

Murray, CBE (8 May 1869 – 28 July 1923)[1] was

a Scottish medical pioneer, and a member of the Women's Social and Political

Union suffragettes.[2] From

1914 to the end of her life, she lived with her partner and doctor Louisa

Garrett Anderson.[3]

Before that, Murray lived for a number of years with Dr

Elsie

Inglis, founder of the

Scottish Women’s Hospitals, in Edinburgh. In May 1915, Drs

Louisa Garrett Anderson

and Flora Murray founded the Endell

Street military hospital in London and from 1916 onwards, women doctors began

to work in hospitals on the front line in Malta, Salonika, Egypt, India, East

Africa and Palestine.

Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson, a formidably competent couple,

established the first of the hospitals set up and staffed by women in Europe

and Russia during the First World War in a Parisian hotel in September 1914.

Murray’s partner, Louisa Garrett Anderson, was the daughter of Elizabeth Garrett

Anderson, a woman whose story is central to the mid-Victorian women’s

movement and whose famously determined struggle to become a doctor placed her

as the first woman on the Medical Register in 1865. Murray and Anderson found

each other through the suffrage campaign. Their intimate companionship,

‘effectively a marriage’ marked by identical diamond rings, lasted until

Murray’s death in 1923; the gravestone in the churchyard near where they lived

in Buckinghamshire bears the epitaph ‘We were gloriously happy’.

Unlike the mass of women who had female partners during the period

1890-1960, there is information about a fascinating group of pioneering women

doctors in Britain: there are biographies and auto-biographies, appearances in

contemporary reminiscences and surveys of successful women, obituaries and

entries in the Dictionary of National Biography and Who's Who. These

particular women — Louisa

Martindale, Louisa Aldrich

Blake, Flora Murray,

Octavia Wilberforce and

their partners — formed a relatively cohesive group united by their common

profession of medicine and by geographical location, social class, and strong

ties of friendship and respect. However, while there is a relative profusion

of material charting their lives, its emphasis is on their professional,

rather than their personal, lives. It is these women's careers as doctors, the

hospitals in which they worked, the practices they built up, the research

articles that they wrote, in essence the contribution that they made to

medicine, that is the focus of interest.

Murray was born on 8 May 1869 at Murraythwaite, Dumfries,

Scotland, the daughter of Grace Harriet Graham and John Murray, a landowner and Royal

Navy captain.[4] Murray

was the fourth of six children. One of her earliest involvements in the

medical field was attending the London Hospital in Whitechapel in 1890. She

attended as a probationer nurse, for a six-month course. Murray decided on her

career in medicine and went on to study in the London

School of Medicine for Women in 1897.[5]

Murray attended school in Germany and

London before going on to study to be a doctor at the London

School of Medicine for Women.[6] She

then proceeded to work as a Medical assistant for 18 months at an asylum at

the Crichton

Royal Institution in Dumfriesshire.

This experience was crucial in her writing of her MD thesis called 'Asylum

Organization and Management' (1905).[5] She

completed her medical education at Durham

University, receiving her MB BSc in 1903, and MD in

1905. She received a Diploma in Public Health from the University

of Cambridge in 1906.[6]

During her time in Scotland, Murray lived in Edinburgh with Dr Elsie

Inglis, founder of the Scottish Women's Hospitals movement.[7] Historians

such as Hamer and Jennings have argued that Murray had her "first serious

lesbian relationship" with Elsie Inglis.[8][7]

In 1905 Murray was a medical officer at the Belgrave

Hospital for Children in London and then an anaesthetist at

the Chelsea

Hospital for Women. In 1905 The

Lancet published an article that she authored on the use of anaesthetic in

children, titled Ethyl chloride as an anaesthetic for children.[9]

Dr Flora Murray (1869–1923)

Francis Dodd (1874–1949)

Royal Free Hospital

Flora Murray (front row, second on right) and Louisa Garrett Anderson

(front row, first on right), with colleagues outside the Hôtel Claridge, 1914

Murray's hand in women's suffrage first started when she became a

participant and activist of Millicent

Fawcett's National

Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. She then continued her work in

women's suffrage as a supporter of Women's Social and Political Union. She

also became a consistent participant in the militant movement, offering her

services as a practitioner including at the Pembroke Gardens nursing home for

suffragettes recovering from force-feeding, run by Nurses Catherine

Pine and Gertrude

Townend.[10]

She took a leadership role and showed her value as an activist by speaking at

public gatherings, becoming a member in the 1911 census protest, and using her

medical knowledge and skill to treat her fellow suffragettes who experienced

injuries through their work as activists.[5] She

looked after Emmeline

Pankhurst and other hunger-strikers after their release from prison and

campaigned with other doctors against the forcible

feeding of prisoners.[11]

In 1912 she founded the Women's Hospital for Children at 688 Harrow

Road with Louisa

Garrett Anderson. It provided health

care for working-class children

of the area, and gave women doctors their only opportunity to gain clinical

experience in pediatrics in London; the hospital's motto was Deeds not Words.[11]

When the First

World War broke out, Murray and her partner Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson

founded the Women's Hospital Corps (WHC), and recruited women to staff it.[12] Believing

that the British War Office would reject their offer of help, and knowing that

the French were in need of medical assistance, they offered their assistance

to the French Red Cross.[13] The

French accepted their offer and provided them the space of a newly built hotel

in Paris as their hospital.[11] Flora

Murray was appointed Médecin-en-Chef (chief physician) and Anderson became the

chief surgeon.[13]

Murray reported in her diary that visiting representatives of the British War

Office were astonished to find a hospital run successfully by British women,

and the hospital was soon treated as a British auxiliary hospital rather than

a French one.[13] In

addition to the hospital in Paris, the Women's Hospital Corps also ran another

military hospital in Wimereux.[11]

In January 1915, casualties began to be evacuated to England for treatment.

The War Office invited Murray and Anderson to return to London to run a large

hospital, the Endell

Street Military Hospital (ESMH), under the Royal

Army Medical Corps. ESMH treated almost 50,000 soldiers between May 1915

and September 1919 when it closed.[11]

After the war ended, Murray returned to Harrow Road hospital which was renamed

Roll of Honour Hospital, where she continued her work as a private

practitioner. Her diary about her experiences of the War became a book

titled Women as Army Surgeons: Being the History of the Women's Hospital Corps

in Paris (1920). The book's dedication reads, "To Louisa Garrett Anderson /

Bold, cautious, true and my loving companion."[8]

Lack of funding eventually led to the closure of the Roll of Honour Hospital,

and also the retirement of both Murray and Anderson. They moved to a cottage

in Paul End, in Penn, Buckinghamshire.[5]

Murray suffered from cancer and

died on 28 July 1923, aged 54. Her death occurred shortly after her surgery in

a nursing home in Hampstead,

London. Her lifelong partner was by her side.[11] Murray

left everything to Anderson in her will.[14] Murray

is buried at the Holy Trinity Church at Penn in a shared grave with Anderson. Their

tombstone reads, "We have been gloriously happy."[1]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flora_Murray

- Oakley, Ann. Women, Peace and Welfare . Policy Press. Edizione del

Kindle.

- Sexual Cultures in Europe: Themes in sexuality, Franz Eder, Gert

Hekma, Lesley A. Hall, Manchester University Press, 1999.

- A Lesbian History of Britain: Love and Sex Between Women Since 1500,

Rebecca Jennings, Greenwood World Pub., 2007

- Crawford, Elizabeth. The Women's Suffrage Movement (Women's and Gender

History) (p.432). Taylor and Francis. Edizione del Kindle.

Flora

Murray, CBE (8 May 1869 – 28 July 1923)[1] was

a Scottish medical pioneer, and a member of the Women's Social and Political

Union suffragettes.[2] From

1914 to the end of her life, she lived with her partner and doctor Louisa

Garrett Anderson.[3]

Before that, Murray lived for a number of years with Dr

Elsie

Inglis, founder of the

Scottish Women’s Hospitals, in Edinburgh. In May 1915, Drs

Louisa Garrett Anderson

and Flora Murray founded the Endell

Street military hospital in London and from 1916 onwards, women doctors began

to work in hospitals on the front line in Malta, Salonika, Egypt, India, East

Africa and Palestine.

Flora

Murray, CBE (8 May 1869 – 28 July 1923)[1] was

a Scottish medical pioneer, and a member of the Women's Social and Political

Union suffragettes.[2] From

1914 to the end of her life, she lived with her partner and doctor Louisa

Garrett Anderson.[3]

Before that, Murray lived for a number of years with Dr

Elsie

Inglis, founder of the

Scottish Women’s Hospitals, in Edinburgh. In May 1915, Drs

Louisa Garrett Anderson

and Flora Murray founded the Endell

Street military hospital in London and from 1916 onwards, women doctors began

to work in hospitals on the front line in Malta, Salonika, Egypt, India, East

Africa and Palestine.