Franklin Edward "Frank" Kameny (May 21, 1925 – October 11, 2011[1])

was an American gay rights activist. He has been referred to as "one of the

most significant figures" in the American gay rights movement.[2]

Franklin Edward "Frank" Kameny (May 21, 1925 – October 11, 2011[1])

was an American gay rights activist. He has been referred to as "one of the

most significant figures" in the American gay rights movement.[2]Queer Places:

103-17 115th St, Jamaica, NY 11419, Stati Uniti

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Queens College, 65-30 Kissena Blvd, Flushing, NY 11367, Stati Uniti

5020 Cathedral Ave NW, Washington, DC 20016, USA

Congressional Cemetery, 1801 E St SE, Washington, DC 20003, Stati Uniti

Franklin Edward "Frank" Kameny (May 21, 1925 – October 11, 2011[1])

was an American gay rights activist. He has been referred to as "one of the

most significant figures" in the American gay rights movement.[2]

Franklin Edward "Frank" Kameny (May 21, 1925 – October 11, 2011[1])

was an American gay rights activist. He has been referred to as "one of the

most significant figures" in the American gay rights movement.[2]

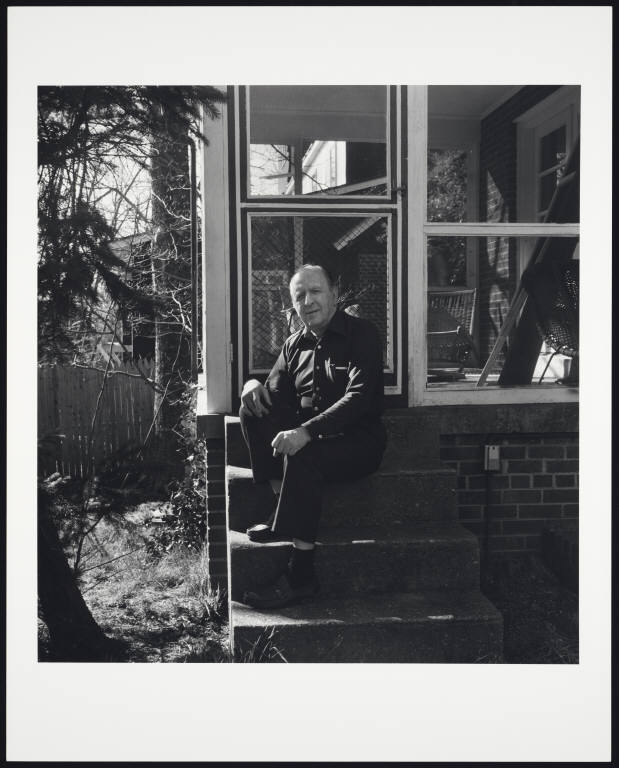

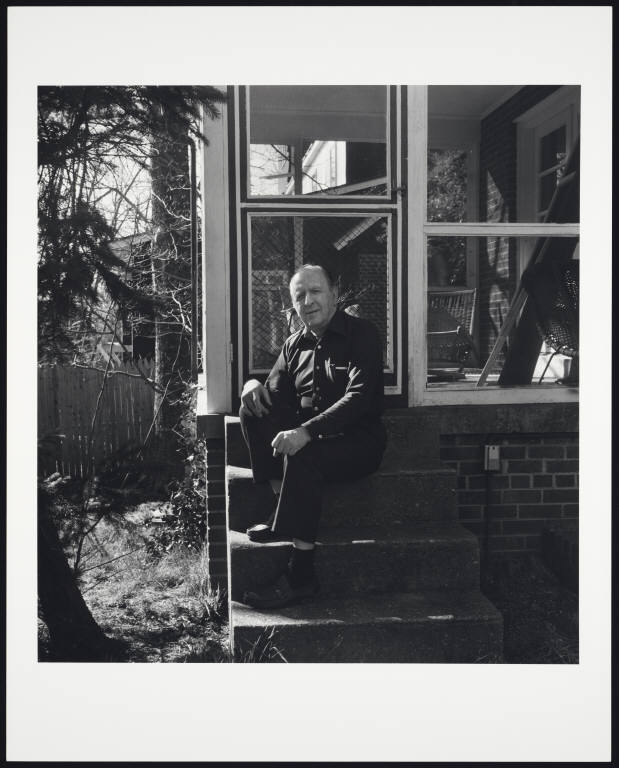

Frank Kameny is profiled in ''Family: a portrait of gay and lesbian America'', by Nancy Andrews (1994).

In 1957, Kameny was dismissed from his position as an astronomer in the U.S. Army's Army Map Service in Washington, D.C. because of his homosexuality,[3] leading him to begin "a Herculean struggle with the American establishment" that would "spearhead a new period of militancy in the homosexual rights movement of the early 1960s".[4]

Kameny formally appealed his firing by the U.S. Civil Service Commission due to homosexuality.[5] Although unsuccessful, the proceeding was notable as the first known civil rights claim based on sexual orientation pursued in a U.S. court.[6]

Kameny was born to Ashkenazi Jewish parents in New York City. He attended Richmond Hill High School and graduated in 1941. In 1941, at age 16, Kameny went to Queens College to learn physics and at age 17 he told his parents that he was an atheist.[7][8] He was drafted into the United States Army before completion. He served in the Army throughout World War II in Europe, and later served 20 years on the Selective Service board.[9] After leaving the Army, he returned to Queens College and graduated with a baccalaureate in physics in 1948. Kameny then enrolled at Harvard University; while a teaching fellow at Harvard, he refused to sign a loyalty oath without attaching qualifiers, and exhibited a skepticism against accepted orthodoxies.[7] He graduated with both a master's degree (1949) and doctorate (1956) in astronomy. His doctoral thesis was entitled A Photoelectric Study of Some RV Tauri and Yellow Semiregular Variables[10] and was written under the supervision of Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin.

Photo by

Robert Giard, Rights Notice: Copyright Jonathan G. Silin

(jsilin@optonline.net)

While on a cross-country return trip from Tucson, where he had just completed his research for his PhD thesis, he was arrested by plainclothes police officers at a San Francisco bus terminal after a stranger had approached and groped him. He was promised that his criminal record would be expunged after serving three years' probation, relieving him from worrying about his employment prospects and any attempt at fighting the charges.[11]

Relocating to Washington, D.C., Kameny taught for a year in the Astronomy Department of Georgetown University and was hired in July 1957 by the United States Army Map Service. When they learned of his San Francisco arrest, Kameny's superiors questioned him, but he refused to provide information regarding his sexual orientation. Kameny was fired by the commission soon afterward. In January 1958, he was barred from future employment by the federal government. As author Douglass Shand-Tucci later wrote,

Kameny was the most conventional of men, focused utterly on his work, at Harvard and at Georgetown... He was thus all the more rudely shocked when the same fate befell him as we've seen befall Prescott Townsend, class of 1918, decades before... He was arrested. Later he would be fired. And, like Townsend, Kameny was radicalized.[12]

Kameny appealed his firing through the judicial system, losing twice before seeking review from the United States Supreme Court, which turned down his petition for certiorari.[5] After devoting himself to activism, Kameny never held a paid job again and was supported by friends and family for the rest of his life. Despite his outspoken activism, he rarely discussed his personal life and never had any long-term relationships with other men, stating merely that he had no time for them. He stated, "If I disagree with someone, I give them a chance to convince me they are right. And if they fail, then I am right and they are wrong and I will just have to fight them until they change."[13]

Kameny eschewed conventional racial designations; throughout his life, he consistently cited his race as "human".[14]

In 1961 Kameny and Jack Nichols, fellow co-founder of the Washington, D.C., branch of the Mattachine Society, launched some of the earliest public protests by gays and lesbians with a picket line at the White House on April 17, 1965.[15][16] In coalition with New York's Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, the picketing expanded to target the United Nations, the Pentagon, the United States Civil Service Commission, and Philadelphia's Independence Hall for what became known as the Annual Reminder for gay rights. Kameny also wrote to President Kennedy asking him to change the rules on homosexuals being purged from the government.[17]

In 1963, Kameny and Mattachine launched a campaign to overturn D.C. sodomy laws; he personally drafted a bill that finally passed in 1993.[15] He also worked to remove the classification of homosexuality as a mental disorder from the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.[15]

In 1980, Bruce Voeller commissioned Don Bachardy to create a series of portraits of twelve leaders of the gay and lesbian rights movement. The subjects included Voeller, Phyllis Lyon, Del Martin, Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings, Troy Perry, Jean O'Leary, Charles Brydon, James Foster, David Goodstein, Morris Kight, Elaine Noble. Many were high-profile business-people, politicians, and publishers as well as influential activists. Bachardy’s partner Christopher Isherwood privately referred to Voeller’s circle as the ‘Gay Elite’. Sittings were largely arranged in Bachardy’s home town of Los Angeles, although a handful were done during a trip he made to New York in October 1980. Following Voeller's death, Lucik presented the portrait series to the Human Sexuality Collection, Cornell University, in 1995.

In 1957, Frank Kameny was dismissed from his civilian government joh because he was gay. The World War II veteran with a Harvard Ph.'D. fought his dismissal, but was unable to keep the job or get another in the burgeoning field of astronomy. After his dismissal Frank became obsessed with fighting for gay rights and against discriminatory fed¬ eral employment practices. In 1961, he and about a dozen others formed the Mattachine Society of Washington, an affiliate of an early gay organization that had been started eleven years earlier in Los Angeles. At a time when others hid from government surveillance, Mattachine of Washington put FBI director J. Edgar Hoover on its mailing list, and the unsolicited copies of Mattachine's newsletter, The Gazette, caught the FBI off guard. Hoover demanded that his subscription be canceled. Mattachine members replied that they would remove Hoover's name from their list if he removed their names from the FBI's lists. Hoover's subscription continued until his death in 1972. Frank was an early leader in disputing the belief, widely held even among fellow gays, that homosexuality was a sickness. Since 1968, he has worked full-time handling the cases of gays who have been denied security clearances or are facing clearance investigations or military discharge. At sixty-seven, Frank lives alone in Washington, D.C. He was photographed one afternoon while he worked in his home office. In the 1950s and '60s it was a much more repressive context. There were no protections. Whether it was federal employment or private employment, the general rule of thumb was that if you were known to be gay you didn't obtain or retain the job, period. In 1957, I was fired from the federal government on the grounds of being gay. That was all that was necessary. Being gay was the basis for total disqualification for federal civil service. There was nothing more that was needed. I was an astronomer in the Army Map Service. At the time I lost my job, the space age was just barely opening up. Had I not been fired when I was, I would have shifted over to the newly formed NASA. I still like to have dreams that I might very well have been one of the astronauts. I would have loved that. That's one of the things that I regret. That all went down the drain. I had never been one to slink around in a closet. They learned that I was gay, and proceeded to dismiss me. It's simply sheer, pure, unqualified, distilled, concentrated bigotry. I was the first who fought my dismissal all the way, including writing my own petition for the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court chose not to take the case. I've always had a burning sense of justice. But, of course, there are too many injustices in the world. You can't address them all. I would not have felt right if I hadn't followed my own case to the end of the avenue. And even if my own personal case was over, well, we had to fight this. So I continued and got drawn into it. My feeling was that by taking cases I could cause changes. And in fact I did. The Civil Service Commission, which covered employment of all federal employees, said, "We will not hire gays." They don't have that policy anymore. I got rid of it after an eighteen-year fight. They made their announcement on July 3, 1975—announcing, in effect, not in these words, that they were changing their policy to suit me. They called me up in advance to tell me.

My published books: