Partner Alexander Robertson James, Lucien Price

Queer Places:

Cornell University (Ivy League), 410 Thurston Ave, Ithaca, NY 14850

1522 Chateau St, Pittsburgh, PA 15233

94 Charles St, Boston, MA 02114

Smithfield East End Cemetery

Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA

Frederick

A. "Fritz" Demmler (February 3, 1888 - November 2, 1918) was an artist from Pittsburgh. He attended Cornell University (1906-1909) and Boston Museum School (1909-1913) and died in WWI.

Frederick

A. "Fritz" Demmler (February 3, 1888 - November 2, 1918) was an artist from Pittsburgh. He attended Cornell University (1906-1909) and Boston Museum School (1909-1913) and died in WWI.

Frederick A. Demmler was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania in 1888. He was, it appeared, of German extraction. His grandfather, who had wished to become an artist, had come to America in a period when artists were about as much in request among us as concert pianists on a cattle ranch. He had earned his living as an architectural sculptor. The talent plunged, like a river, underground for a generation; then reappeared. The father and grandfather put their heads together and resolved that he should have his chance.

Alexander Robertson James befriended a fellow student at the Museum School, a strapping (through socially diffident) young man from Pittsburgh named Frederick Demmler, who became his studio-mate. According to a mutual friend, "The two young painters proceeded to form an offensive and defensive alliance. Where one was, there was the other also... It was good to see the pair together: two thoroughbreds. Both athletes, both artists, one dark, the other fair, both about the same height and build." The observer here was Lucien Price, Harvard-educated art critic for the Boston Evening Transcript, who published this adoring eulogy to his lover the year after Demmler was killed on the Belgian frontier - pathetically, just days before the Armistice was signed in 1918.

There had been two years in Cornell, 1906-1909, before he moved to Boston, 1909-1913, and studied under Horatio S. Stevenson and at the School of the Boston Museum of Art. He shared a studio at 94 Charles Street, Boston, with Ralph Heard, small, slender, fair, escaped from a western military academy of which he could tell tales that froze the blood; and Irving Sisson, a tall, rangy Berkshire Yankee, dry and droll, an Artemus Ward turned art student (though known as 'Siss ' it would never have occurred to anyone to call him " Sissie," and if anyone had been so rash, Sisson's grim reply would have been, like the man in the yarn, " Smile when you say that"). Their room was a first act stage-set for an American version of La Boheme. It was large, low-ceiled, and had one of those sepulchral white marble mantel-pieces of the black walnut period. There was an iron bed and a cot, a gaslight always out of kilter, a writing-table strewn with pipes, unanswered letters, tiny bottles of india ink, drawing pens, crayons, thumb tacks, jars holding bouquets of paint brushes, and scurrilous caricatures of one another scrawled on scraps of white cardboard. The place reeked with that heavenly odor of paint tubes. By the window was a drawing board and portfolios. Canvases were stacked in a dark corner, faces to the wall. Their windows looked into a deep courtyard formed by a triangle of tall brick houses, — the rears of houses on Charles and Brimmer Streets, the fronts of three quaint Italianate red-brick dwellings, — all enclosing a tiny greensward on which slender poplars rustled their glossy leaves. In the farthest corner of this court rise the walls and mullioned windows of the Church of the Advent, and on mild evenings when casements were open, the thrush- like voices of the choir boys over the melodious thunder of great organ floated up to these windows.

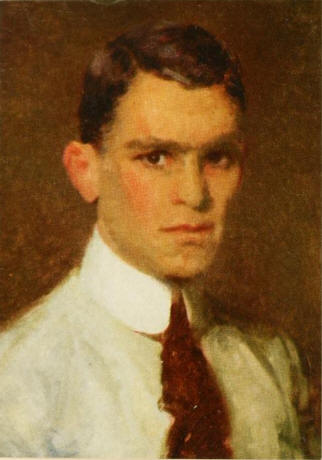

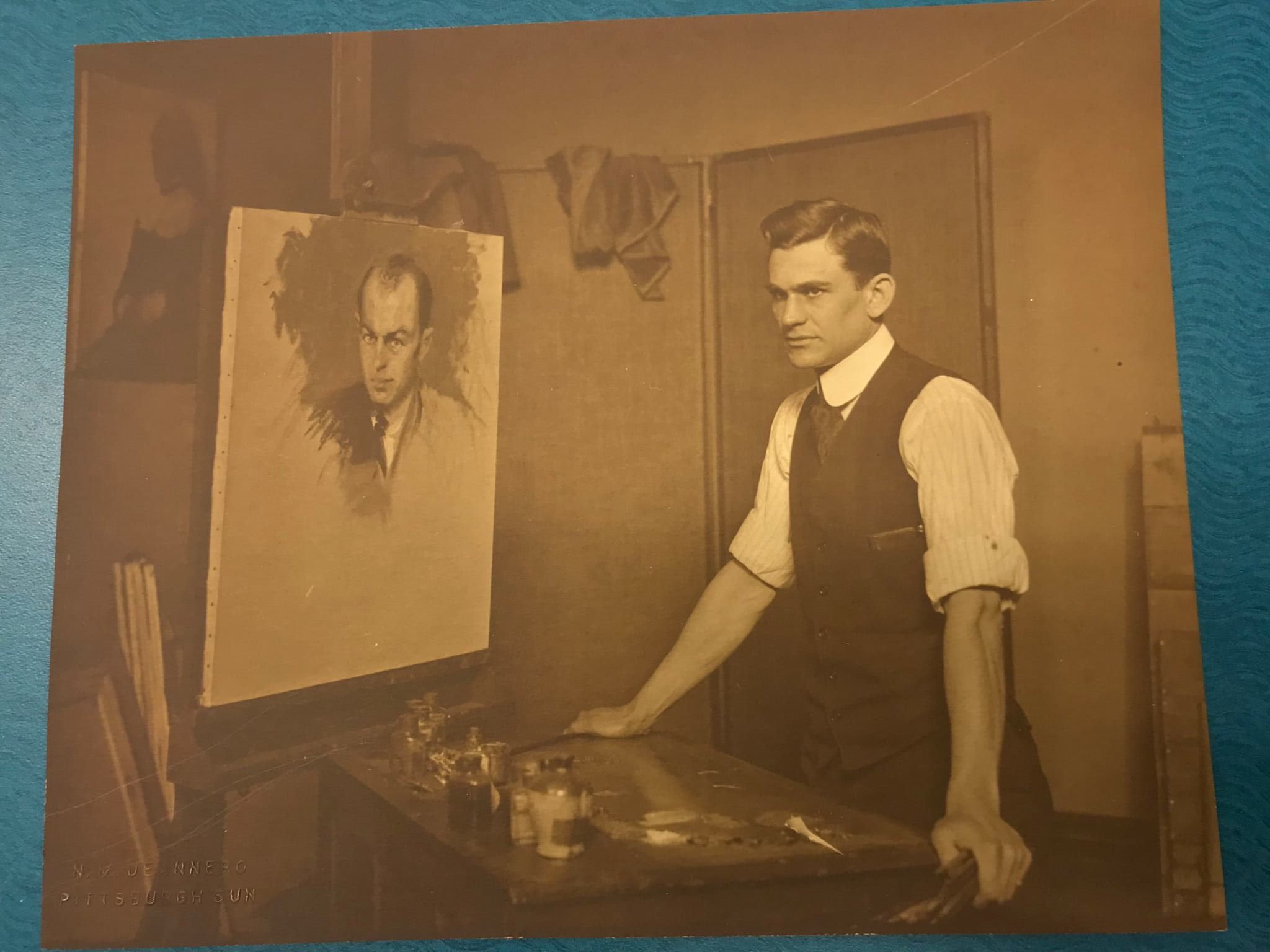

DM 115. Fred A. Demmler in his studio in 1917 with his portrait of Haniel Long. Unidentified portrait, upper left. [Westmoreland]

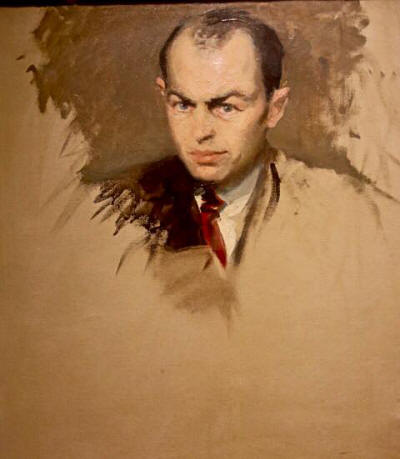

DM 107. Lucien Price, signed and dated lower right: Fred A. Demmler 1916. 36 3/16" by 30" oil on canvas. Nahant Historical Society, Nahant, Massachusetts. Painted on commission of Price as a birthday gift to Frederick H. Middleton, Demmler began this portrait on Sunday April 1, 1916, in Lucien Price's apartment at 51 Pinckney St., Boston. It later became the possession of William Demmler, East Weymouth, MA, and after that, William O. Taylor, Chairman of the Boston Globe. Taylor, after his retirement, donated the portrait to Nahant Historical Society in 2002.

DM 120. George M. P. Baird, 1917. 41.5" x 31.5" oil on canvas. [Westmoreland; photo: Kaufmann]

Vera Lillian Parsons by Fred Demmler

The Black Hat (Mary Ethel Schreiner) by Frederick Demmler

Haniel Long. Portrait from a sitting, 1918/1918. Location: Special Collections, Carnegie Mellon University Libraries.

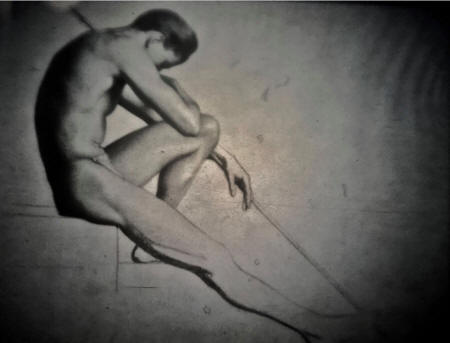

DM 62. Seated Male Nude with Javelin. 18" x 23.5" charcoal. [Item location not known. From a slide; Carnegie. Photo: Dorli McWayne, 1974.]

Demmler had rowed in his class 8th on Lake Cayuga. Alexander James also was an avid amateur sportsman. Basketball and baseball had been his passions as a schoolboy. Like his father, he loved the outdoors and spent much of his time thinking in the woods and hills at Chocorua. Demmler joined Aleck there over their winter vacation in 1913, and as their friendship deepened, they both resolved to join forces by spending the next academic year in Europe: visiting the great galleries and museums, setting up their easels, and learning what they might from the Old (and newer) Masters. Like the rest of the world, not knowing of the global cataclysm that lay ahead, the pair shipped off across the Atlantic in late June 1914. After spending a few days at Edinburgh (their ship's destination), they arrived in London and took up residence in a spare flat in Carlyle Mansions that Alexander's uncle, Henry James, had snagged for his niece, Peggy (Aleck's older sister), who also was travelling with a female companion that summer. Unfortunately, almost from the start of things, Demmler proved himself, according to Henry James, "a dreadful impossibility for any social use whatever." To introduce him among James' circle of acquaintance "would be anguish for Alec & great discomfort for everyone else," he wrote with dismay: "like having the newspaper boy to dine."

James' disapproval might also betray other kinds of social anxiety, especially if the young man's behavior and manner threatened to become perilously indiscreet. Earlier that summer, Demmler had came up to Dublin, NH, accompanied by the diminituve Lucien Price, whom he affectionately nickmaned "the thumb". The two of them, hand (Demmler had very large and finely muscled hands) and thumb, proceeded to tell Aleck of a recent trip they had made down to Provincetown "in the hopes of passing an hour or so with out friends who are there "learning to paint."

Whatever reconciliation (or rupture) the two young men may have achieved (or suffered), the outbreak of the European war forced them to abandon their plans for traveling to Munich that August and to head home instead. In Aleck's case, this about-face was matched by another, perhaps more startling, one: arriving back in Cambridge, he abruptly announced his betrothal to Miss Frederika Paine (of Newport, Rhode Island), another student whom he had first met at the Museum School. Their marriage was deferred for two years (almost all the other Jameses were fiercely opposed to the union), but Aleck knew that at that moement someone else's feeling also had to be taken into account. "I haven't time to tell you anythingof this morning's happenings," Aleck wrote to his intended, "save that Fred Demmler phoned me that he got in last evening and was leaving today at one. I put off writing you in order to "get to him" as soon as possible and impart a few necessary facts for him to bear in mind."

Lucien Price describes a scene in his room at 51 Pinckney, Boston, on January 31, 1914. He has just settled in by the hearth for an evening of reading when Fred Demmler turns up along with his former roommate Ralph Heard (Janet Hart's grandfather), another artist. At the time Demmler, whom Price calls Fritz, having graduated from the Museum School, has returned to Pittsburgh and opened a studio: "In my wing chair, beside a ruddy hearth, a reading lamp on the table just aft my left elbow . . . I was ploughing into a Socialist book, rain whipping window panes and purling over the sills, with now and then a drop to fall from the chimney’s throat hissing onto the fire. Wind roared across the flue; the stream of rain made confused noises outside in the court where the wind drew whistling, too, through the boughs of the ash. A rap sounded on my door panel. “Come!” said I. It was repeated. “Come!” I said again. The door opened and framed in the blackness of its opening stood Fritz Demmler. Ralph was grinning behind him. Gasps and ejaculations. He should have been far off in Pittsburgh. It was a very Fritz, in the flesh and an overcoat dripping with rain. They got into slippers and dressing gowns and camped beside the fire, lighting cigarettes at the lamp. Fritz had stepped off a train at Back Bay station two hours earlier, plunged through the rain to 94 Charles and frozen Ralph with surprise. There was some question of Fritz having deceased and this being his watery apparition, but the ghost was solid. It appeared, at the end of the evening’s chat, (with Fritz’s inseparable modesty), that he was bound for Exeter to paint the portrait of one of the schoolmasters there, a neighbor of the Gouards whose mother he had painted a year ago. Also that he had just completed a portrait of a bank president in Pittsburgh before leaving. The evening sped with discussions of Christianity, conversion, marriage, sex, socialism, and miscellaneous ribaldry for enlivenment."

Demmler was a member of the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh, and the Fellowship of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1916 he was awarded the third prize at the exhibition of the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh. In May, 1917, Demmler went to Boston from Pittsburgh. Lucien Price was in Parkersburg, West Virginia. He went there. Conscription impended. For three days, tramping about the scrubby countryside, rambling along the banks of the Ohio, rowing up the swift, muddy current of the Kanawah, the dilemma of a man born to create and commandeered to destroy was threshed out. Never before had he spoken so freely. The economic causes of the trouble he understood fairly well, but it was startling with what a seeing eye he pierced the illusions which beset that time. By that faculty of divination peculiar to the artist's mind he reached, at one leap, conclusions which the thinker only arrives at after laborious effort. And he was a young man without an illusion left, steadfastly looking the ugliest facts of our social order in the face. On the last evening of his stay Demmler and Price were standing on the steel spider web of a suspension bridge which spans the Ohio, watching a sunset unfurl its banners of blood and fire. All day there had been thunder and rain, and eastward behind the towers and spires of the city skyline still hung the retreating clouds, sullen and dark. Fritz pointed to where, against that gloomy cloud bank, high above the city and gilded red from the setting sun, rose two symbols: one on the tip of a spire, the other on the staff atop a tower: cross and flag. "Church," said he grimly, "and State." The next day he returned to Pittsburgh to register for the draft. He was not called until the following April, 1918. Twice that winter he went to Boston. Number 94 Charles Street had been dismantled. But the third-floor-back on Pinckney Street, Lucien Price's house, received him with an extra cot for bivouac.

On November 2, 1918, nine days before armistice, Fred Demmler died of shrapnel wounds to the left side in Evacuation Hospital No. 5, Staden, Belgium. Demmler, a former pacifist, was the leader of a machine gun squadron in Company C, 136th Machine Gun Battalion. The Demmler family did not know of Fred's death until November 23, 1918. Fred Demmler's body would be shipped home for burial in Pittsburgh on April 22, 1921.

In 1919 Lucien Price wrote "Immortal Youth, A Study in the Will to Create". Historian Jennie Benford wrote a piece for the Western Pennsylvania History Magazine, Vol. 100, No. 4. about World War I soldier and poet Frank Hogan. The article discussed a two-book set printed in 1918 titled The Soldier’s Progress and Carnegie Tech War Verse. The books were edited by English professor Haniel Long of the Carnegie Institute of Technology (present-day Carnegie Mellon University), who once sat to have his portrait painted by Fred Demmler. The impression that Demmler left on Haniel Long was obviously an impactful one, enough to carry the memory of the young artist into a literary piece written in 1935 by Long called Pittsburgh Memoranda. Long wrote a chapter about Demmler in his book, along with other Pittsburgh notables such as Andrew Carnegie, John Brashear, George Westinghouse, and Stephen Foster. Composer Harvey B. Gaul wrote a piece of music in 1919 for the organ titled, “Chant for Dead Heros,” published as a dedication to Sergeant Fred Demmler and Corporal Francis Hogan.

My published books: