Queer Places:

13 Ashburton Pl, Cambridge, MA 02139

20 Quincy St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Winthrop Square, Cambridge, MA 02138

16 Lewes Cres, Brighton BN2 1GB, UK

21 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, London SW3 5RA, UK

4 Bolton St, Mayfair, London W1J, UK

15 Beaumont St, Oxford OX1 2NA, UK

Hale House, 34 De Vere Gardens, Kensington, London W8 5AQ, UK

Lamb House, West St, Rye TN31 7ES, UK

Cambridge Cemetery, Cambridge, MA 02138

Westminster Abbey, 20 Deans Yd, Westminster, London SW1P 3PA, UK

Henry James,

OM (15 April 1843 – 28 February 1916) was an American author regarded as a

key transitional figure between

literary realism and

literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest

novelists in the English language. He was the son of

Henry James Sr. and the brother of renowned philosopher and psychologist

William James and diarist

Alice

James. John Singer Sargent reputedly exercised a strange power over Henry

James, "a great queen-bee," who was "mesmerized by John, as one is mesmerized

by an exotic flower." Sally Ledger has argued that male writers tended to present female

same-sex relationships in a different way from women novelists, explicity

pathologising their New Women characters as unmarried and lesbian, as in the

case of Olive Chancellor in Henry James' The

Bostonians (1886) and Cecilia Cullen in George

Moore's A Drama in Muslin (1886).

Henry James,

OM (15 April 1843 – 28 February 1916) was an American author regarded as a

key transitional figure between

literary realism and

literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest

novelists in the English language. He was the son of

Henry James Sr. and the brother of renowned philosopher and psychologist

William James and diarist

Alice

James. John Singer Sargent reputedly exercised a strange power over Henry

James, "a great queen-bee," who was "mesmerized by John, as one is mesmerized

by an exotic flower." Sally Ledger has argued that male writers tended to present female

same-sex relationships in a different way from women novelists, explicity

pathologising their New Women characters as unmarried and lesbian, as in the

case of Olive Chancellor in Henry James' The

Bostonians (1886) and Cecilia Cullen in George

Moore's A Drama in Muslin (1886).

He is best known for a number of novels dealing with the social and marital

interplay between emigre Americans, English people, and continental Europeans

– examples of such novels include

The Portrait of a Lady,

The Ambassadors, and

The Wings of the Dove. His later works were increasingly experimental.

In describing the internal states of mind and social dynamics of his

characters, James often made use of a personal style in which ambiguous or

contradictory motivations and impressions were overlaid or closely juxtaposed

in the discussion of a single character's psyche. For their unique ambiguity,

as well as for other aspects of their composition, his late works have been

compared to

impressionist painting.

In addition to voluminous works of fiction, James published articles and

books of criticism,

travel, biography, autobiography, and plays. Born in the United States,

James largely relocated to Europe as a young man and eventually settled in

England, becoming a

British subject in 1915, one year before his death. James was nominated

for the

Nobel Prize in Literature in 1911, 1912, and 1916.[1]

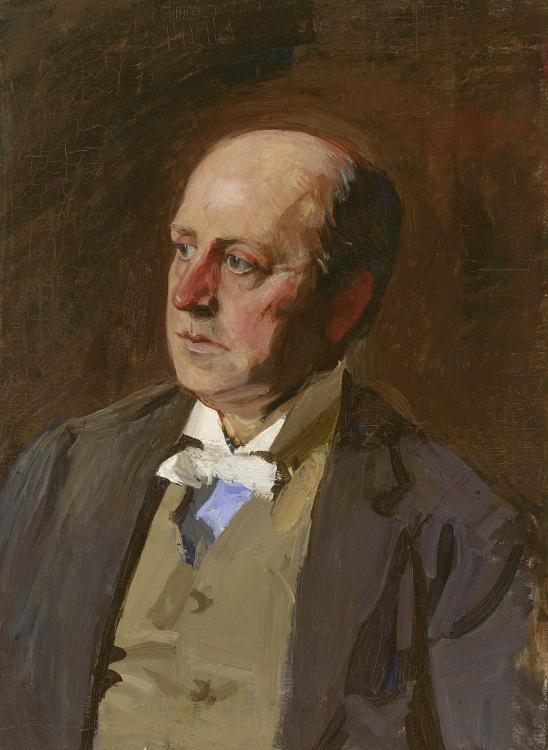

Henry James by Ellen Emmet Rand

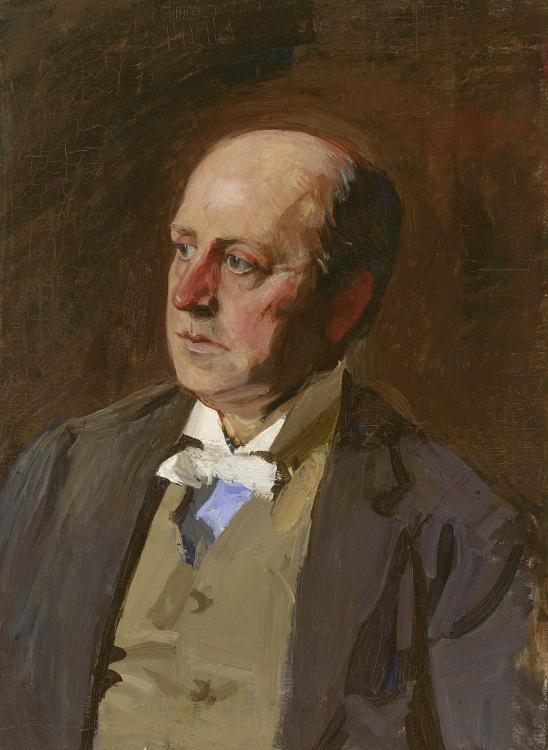

Henry James

by Jacques-Emile Blanche (1861-1942)

Westminster Abbey, London

James regularly rejected suggestions that he should marry, and after

settling in London proclaimed himself "a bachelor".

F. W.

Dupee, in several volumes on the James family, originated the theory that

he had been in love with his cousin Mary ("Minnie") Temple, but that a

neurotic fear of sex kept him from admitting such affections: "James's

invalidism ... was itself the symptom of some fear of or scruple against

sexual love on his part." Dupee used an episode from James's memoir A Small

Boy and Others, recounting a dream of a Napoleonic image in the Louvre, to

exemplify James's romanticism about Europe, a Napoleonic fantasy into which he

fled.[19][20]

Dupee had not had access to the James family papers and worked principally

from James's published memoir of his older brother, William, and the limited

collection of letters edited by Percy Lubbock, heavily weighted toward James's

last years. His account therefore moved directly from James's childhood, when

he trailed after his older brother, to elderly invalidism. As more material

became available to scholars, including the diaries of contemporaries and

hundreds of affectionate and sometimes erotic letters written by James to

younger men, the picture of neurotic celibacy gave way to a portrait of a

closeted homosexual.

Between 1953 and 1972,

Leon Edel

authored a major five–volume biography of James, which accessed unpublished

letters and documents after Edel gained the permission of James's family.

Edel's portrayal of James included the suggestion he was celibate. It was a

view first propounded by critic

Saul Rosenzweig in 1943.[21]

In 2004 Sheldon M. Novick published Henry James: The Young Master,

followed by Henry James: The Mature Master. The first book "caused

something of an uproar in Jamesian circles"[22]

as it challenged the previous received notion of celibacy, a once-familiar

paradigm in biographies of homosexuals when direct evidence was non-existent.

Novick also criticised Edel for following the discounted Freudian

interpretation of homosexuality "as a kind of failure."[22]

The difference of opinion erupted in a series of exchanges between Edel and

Novick which were published by the online magazine Slate, with the latter

arguing that even the suggestion of celibacy went against James's own

injunction "live!"--not "fantasize!"[23]

The interpretation of James as living a less austere emotional life has been

subsequently explored by other scholars.[24]

The often intense politics of Jamesian scholarship has also been the subject

of studies.[25]

Author

Colm

Tóibín has said that

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's Epistemology of the Closet made a landmark

difference to Jamesian scholarship by arguing that he be read as a homosexual

writer whose desire to keep his sexuality a secret shaped his layered style

and dramatic artistry. According to Tóibín such a reading "removed James from

the realm of

dead white males who wrote about posh people. He became our contemporary."[26]

Drum-Taps, first published in 1865, is a collection of poetry written by American poet

Walt Whitman during the American Civil War.

Especially interesting, however, somewhat on the other side, is the reaction

from the Jameses—soon to move from Beacon Hill’s Ashburton Place to their more

famous abode on Quincy Street, overlooking Harvard Yard—and particularly from

young Henry, to Whitman’s Civil War poetry, Drum-Taps. Sheldon Novick notes

the book was “making a stir in Boston” and that it was “much admired” by

James’s father and by Ralph

Waldo Emerson. But young Henry “dismissed [it] almost with anger.” All

James’s biographers have to address his initial reaction because in later

years Whitman became virtually James’s favorite American poet. Sheldon Novick

gets it just right, telling very well the tale of how Edith Wharton recalled

James reading Leaves of Grass by her fireplace in Lennox; “his voice filled

the hushed room like an organ adagio.” Adds Novick: “Wharton was delighted to

discover that he thought Whitman, as she did, ‘the greatest of American

poets.’ She was unaware of Henry James’s hostile review of Drum-Taps years

before and of the long process of sexual self-acceptance that had allowed yet

another Harvard man to become a lover of Whitman.”

In the spring of 1865 young Henry performed his “first acts of love” within

sight of, if not actually in, the Back Bay and not with a woman, but with a

man, a fellow Harvard student, no less than young

Oliver Wendell Holmes

Jr.

One of John Singer Sargent's most famous paintings is The Daughters of

Edward Darley Boit, which is the pride of the Musuem of Fine Arts of Boston.

The Boits met Sargent in the late 1870s. One daughter,

Florie Boit, was a lesbian who would

eventually settle into a happy Boston marriage with her cousin,

Jane Boit Patten.

Henry James met Sargent by 1882, the same

year Sargent painted the Boit daughters. He was immediately infatuated with

the painter and asked the Boits to put in a good work for him. But Sargent was

still very attached to his studio mate at the time,

Albert de Belleroche,

whom Sargent painted a very sensuous painting of that year. "Almost

androgynous in appearance, Belleroche displays a sultry sexual presence" and

the painting would be the center of attention in Sargent's London dining room

for the rest of his life. Six years later Sargent would paint another sensual

portrait of a man, the singer George Henschel.

It was so wonderfully erotic that a friend asked Sargent how he could put so

much emotion into a painting. Sargent replied, "I loved him." When Sargent

faced scandal and ruin in Paris for painting the now much admired Portrait of

Madame X in 1884, he took James' suggestion to move to London.

When in 1882 Oscar Wilde

announced to Henry

James, “I am going to Bossston; there I have a letter to the dearest friend of

my dearest friend—Charles Eliot Norton

from Burne-Jones,” James was not only offended at the name-dropping but, in

Richard Ellmann’s words, “revolted by Wilde’s knee breeches, contemptuous at

the self-advertising … and nervous about the sensuality … . James’s

homosexuality was latent, Wilde’s patent.”

Henry James wrote to John

Addington Symonds from Paris on 22 February 1884, referring to his article

on Italy: I sent it you because it was a constructive way of expressing the

good will I felt for you in consequence of what you have written about the

land of Italy – and of intimating to you, somewhat dumbly, that I am an

attentive and sympathetic reader. I nourish for the said Italy an unspeakably

tender passion, and your pages always seemed to say to me that you were one of

a small number of people who love it as much as I do – in addition to your

knowing it immeasurably better. I wanted to recognize this (to your

knowledge); for it seemed to me that the victims of a common passion should

sometimes exchange a look.

When a youthful John Singer Sargent

was first launching his career, some of his closest associates were very

flamboyant. Most conspicuous among them was

Robert

de Montesquiou - "the so-called "Prince of Decadence"" - whose incarnation

of dandified aestheticism was to Paris what

Oscar Wilde's was to London. Another

was Samuel Jean de Pozzi,

whose sexual exploits were almost as legendary as his pioneering work in the

field of gynecology; both aspects of his character were dashingly suggested in

Sargent's full-lenght portrait of 1881, Dr. Pozzi at Home. In the summer of

1885, Sargent have these friends (and the composer

Prince

Edmond de Polignac) a collective letter of introduction to

Henry James, who dutifully arranged a dinner

for them to meet James

Abbott McNeill Whistler for a chance to see the artist's fabled "Peacock

Room" in the home of Frederick

Richards Leyland, a shipping magnate whose house was at 49 Prince's Gate.

According to James, "on the whole nothing that relates to Whistler is queerer

than anything else." That all three Frenchmen would later resurface in the

masterwork A la recherche du temps perdu) of another gay writer,

Marcel Proust, makes the anterior

coincidence queerer still.

James's letters to expatriate American sculptor

Hendrik Christian Andersen have attracted particular attention. James met

the 27-year-old Andersen in Rome in 1899, when James was 56, and wrote letters

to Andersen that are intensely emotional: "I hold you, dearest boy, in my

innermost love, & count on your feeling me—in every throb of your soul". In a

letter of 6 May 1904, to his brother William, James referred to himself as

"always your hopelessly celibate even though sexagenarian Henry".[27]

How accurate that description might have been is the subject of contention

among James's biographers,[28][nb

1] but the letters to Andersen were occasionally quasi-erotic: "I

put, my dear boy, my arm around you, & feel the pulsation, thereby, as it

were, of our excellent future & your admirable endowment."[29]

To his homosexual friend

Howard Sturgis, James could write: "I repeat, almost to indiscretion, that

I could live with you. Meanwhile I can only try to live without you."[30]

His many letters to the many young gay men among his close male friends are

more forthcoming. In a letter to Howard Sturgis, following a long visit, James

refers jocularly to their "happy little congress of two"[31]

and in letters to

Hugh

Walpole he pursues convoluted jokes and puns about their relationship,

referring to himself as an elephant who "paws you oh so benevolently" and

winds about Walpole his "well meaning old trunk".[32]

His letters to

Walter Berry printed by the

Black Sun Press have long been celebrated for their lightly veiled

eroticism.[33]

In 1897–1898 he moved to

Rye, Sussex, and wrote

The Turn of the Screw. 1899–1900 saw the publication of

The Awkward Age and

The Sacred Fount. During 1902–1904 he wrote

The Ambassadors,

The Wings of the Dove, and

The Golden Bowl.

Henry James corresponded in almost equally extravagant language with his many female

friends, writing, for example, to fellow novelist

Lucy Clifford: "Dearest Lucy! What shall I say? when I love you so very,

very much, and see you nine times for once that I see Others! Therefore I

think that—if you want it made clear to the meanest intelligence—I love you

more than I love Others."[34]

To his New York friend

Mary Cadwalader Jones: "Dearest Mary Cadwalader. I yearn over you, but I

yearn in vain; & your long silence really breaks my heart, mystifies,

depresses, almost alarms me, to the point even of making me wonder if poor

unconscious & doting old Célimare [Jones's pet name for James] has 'done'

anything, in some dark somnambulism of the spirit, which has ... given you a

bad moment, or a wrong impression, or a 'colourable pretext' ... However these

things may be, he loves you as tenderly as ever; nothing, to the end of time,

will ever detach him from you, & he remembers those Eleventh St. matutinal

intimes hours, those telephonic matinées, as the most romantic of his

life ..."[35]

His long friendship with American novelist

Constance Fenimore Woolson, in whose house he lived for a number of weeks

in Italy in 1887, and his shock and grief over her suicide in 1894, are

discussed in detail in Edel's biography and play a central role in a study by

Lyndall Gordon. (Edel conjectured that Woolson was in love with James and

killed herself in part because of his coldness, but Woolson's biographers have

objected to Edel's account.)[nb

2]

Henry James settled at Lamb House outside of London in 1897. As closeted as

he was in his earlier years, there is greater documentation from his last

decades regarding his affairs, or at least his romantic infatuations, with

other men. One of these was with an undistinguished sculptor named

Hendrik Andersen. They met

in Rome at the home of Julia Ward Howe's

daughter in 1899 when James was 56 and Andersen was 27. Andersen and his

brothers had been poor carpenters and house painters for the wealthy in

Newport when Isabella Steward

Gardner was taken by their talent and sponsored their travels and

education. Andersen also attracted the interest of Lord

Ronald Gower. The talented

seducer of young men offered to adopt Andersen and make him his heir.

Andersen declined. Gower was close to

Oscar Wilde, who reportedly used him as a model for Lord Henry Wotton in

The Picture of Dorian Gray. Gower was also implicated in the notorious

Cleveland Street Scandal of 1889, though his name did not come up until the

following year. The scandal involved telegraph delivery boys exchanging sex

for money from important men including, it was rumored, the Prince of Wales.

Gower was never indicted. James was infatuated with Andersen and he was

careful to keep him away from Howard Sturgis

and his other gay friends, even disinviting Sturgis when Andersen was

visiting Lamb House. Though the two only met a total of six times, they had

a robust correspondence up until James' death. There is tenderness and

eroticism in the letters. When he learned of the death of Andersen's

brother, for example, James wrote that he wants to put his "hands on you

(oh, how lovingly I should lay them!)" and that he wants to "make you lean

on me as on a brother and a lover, and keep you on and on."

Isabella Stewart Gardner

introduced Gaillard Lapsley to Henry James.

Lapsley, a close friend of George Santayana

at Harvard and perhaps a one-time love interest of

Arthur Little, went on to a

distinguished career as an Oxford don. Through these men, Lapsley met

Edith Wharton and the two became

lifelong close friends.

Henry James became closer to Howard Sturgis

after 1900 when he developed an

intense crush on him. George Santayana wrote that Sturgis "became, save for

the accident of sex, which was not yet a serious encumbrance, a perfect young

lady of the Victorian type."

In 1903, Henry James immortalized the

community of American women sculptors in Rome (Harriet

Hosmer, Edmonia Lewis,

Anne Whitney,

Vinnie Ream;

Emma Stebbins,

Margaret Foley,

Sarah Fisher Ames, and

Louisa Lander) by characterizing

them as “that strange sisterhood of American lady sculptors who at one time

settled upon the seven hills [of Rome] in a white marmorean flock.”

In 1904 he revisited America and lectured on Balzac.

Henry James translated his acquaintance with

Charlotte Cushman’s history

(Cushman was in a relationship with Emma Crow, who was married to her

stepson, Ned Cushman) into the heterosexual plot of The Golden Bowl (1904), in

which a father marries his daughter’s husband’s lover, also named Charlotte.

Henry

James met Edith Wharton at

the Paris home of Edward Darley Boit, whose daughters would be the subject of

the marvelous painting by John Singer

Sargent at the MFA in Boston. They had other connections. Wharton was

friends with Howard Sturgis, whom she had

met in Newport. James had met Sturgis when he was 18 and James was 30. The

Sturgises were an old Yankee Boston family and Howard's father had settled in

London to run the Barings Bank. Later, Wharton and James were involved in a

triangular relationship with

Morton Fullerton, a

Harvard graduate. Introduced to James in 1890 by Harvard Professor Charles

Eliot Norton, Fullerton was a correspondent for the London Times and

"well-groomed and extremely well-dressed, Fullerton, from numerous accounts,

exuded great charm and had powerfully seductive ways, with a slim build, bushy

yet groomed mustache, slicked hair and intense eyes." James was captivated.

"I'd do anything for you," he wrote. James introduced Wharton to Fullerton.

The journalist and bon vivant was involved with the gay circles of Paris and

London. Fullerton dined with the gay poet Paul Verlaine, for example, and

Oscar Wilde turned to him for help when he arrived in Paris bankrupt after

being released from jail. At first, James was intrigued by Fullerton's and

Wharton's attraction and encouraged it. Then he began to feel like a third

wheel as their affair deepened and the two spent increasing amount of time

alone. He grew depressed and left the lovers in France.

In 1906–1910 James

published

The American Scene and edited the "New

York Edition", a 24-volume collection of his works.

By 1909, Henry James was in a reciprocated semi-public infatuation with

Hugh Walpole, a man 40 years his junior. The

reactions of his friends, including gay men, ranged from disapproval to

bemused acceptance. James soon moved on to another younger (in his 30s) man,

Jocelyn Persse.

In 1910 Henry James' brother

William died; Henry had just joined William from an unsuccessful search for

relief in Europe on what then turned out to be his (Henry's) last visit to the

United States (from summer 1910 to July 1911), and was near him, according to

a letter he wrote, when he died.[17]

In 1913 he wrote his autobiographies,

A Small Boy and Others, and

Notes of a Son and Brother. After the outbreak of the First World War

in 1914 he did war work. In 1915 he became a British subject. In 1916 he was

awarded the

Order of Merit. He died on 28 February 1916, in

Chelsea, London. A memorial service was held at Chelsea Old Church, where a

memorial table was later placed in the More Chapel. The design of the tablet

is by American expatriat and gay architect

John Joseph Borie, III. As he requested, his ashes were buried in Cambridge

Cemetery in Massachusetts.[18]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_James

- A Lesbian History of Britain: Love and Sex Between Women Since 1500,

Rebecca Jennings, Greenwood World Pub., 2007

- Anesko, Michael. Henry James and Queer Filiation . Springer International

Publishing. Edizione del Kindle.

- Robb, Graham. Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century .

Pan Macmillan. Edizione del Kindle.

- Homosexuals in History, A Study of Ambivalence in Society, Literature

and the Arts, by A.L. Rowse, 1977

- Dabakis, Melissa. A Sisterhood of Sculptors . Penn State University

Press. Edizione del Kindle.

- The Hub of the Gay Universe, An LGBTQ History of Boston, Provincetown,

and Beyond, by Russ Lopez, 2019

- Shand-Tucci, Douglass. The Crimson Letter . St. Martin's Publishing

Group. Edizione del Kindle.

Henry James,

OM (15 April 1843 – 28 February 1916) was an American author regarded as a

key transitional figure between

literary realism and

literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest

novelists in the English language. He was the son of

Henry James Sr. and the brother of renowned philosopher and psychologist

William James and diarist

Alice

James. John Singer Sargent reputedly exercised a strange power over Henry

James, "a great queen-bee," who was "mesmerized by John, as one is mesmerized

by an exotic flower." Sally Ledger has argued that male writers tended to present female

same-sex relationships in a different way from women novelists, explicity

pathologising their New Women characters as unmarried and lesbian, as in the

case of Olive Chancellor in Henry James' The

Bostonians (1886) and Cecilia Cullen in George

Moore's A Drama in Muslin (1886).

Henry James,

OM (15 April 1843 – 28 February 1916) was an American author regarded as a

key transitional figure between

literary realism and

literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest

novelists in the English language. He was the son of

Henry James Sr. and the brother of renowned philosopher and psychologist

William James and diarist

Alice

James. John Singer Sargent reputedly exercised a strange power over Henry

James, "a great queen-bee," who was "mesmerized by John, as one is mesmerized

by an exotic flower." Sally Ledger has argued that male writers tended to present female

same-sex relationships in a different way from women novelists, explicity

pathologising their New Women characters as unmarried and lesbian, as in the

case of Olive Chancellor in Henry James' The

Bostonians (1886) and Cecilia Cullen in George

Moore's A Drama in Muslin (1886).