Queer Places:

Frida Kahlo Museum, Londres 247, Del Carmen, Coyoacán, 04100 Ciudad de México, CDMX

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈfɾiða ˈkalo]; 6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954[1]) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by the country's popular culture, she employed a naïve folk art style to explore questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class, and race in Mexican society.[2] Her paintings often had strong autobiographical elements and mixed realism with fantasy. In addition to belonging to the post-revolutionary Mexicayotl movement, which sought to define a Mexican identity, Kahlo has been described as a surrealist or magical realist.[3] She is known for painting about her experience of chronic pain.[4]

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈfɾiða ˈkalo]; 6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954[1]) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by the country's popular culture, she employed a naïve folk art style to explore questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class, and race in Mexican society.[2] Her paintings often had strong autobiographical elements and mixed realism with fantasy. In addition to belonging to the post-revolutionary Mexicayotl movement, which sought to define a Mexican identity, Kahlo has been described as a surrealist or magical realist.[3] She is known for painting about her experience of chronic pain.[4]

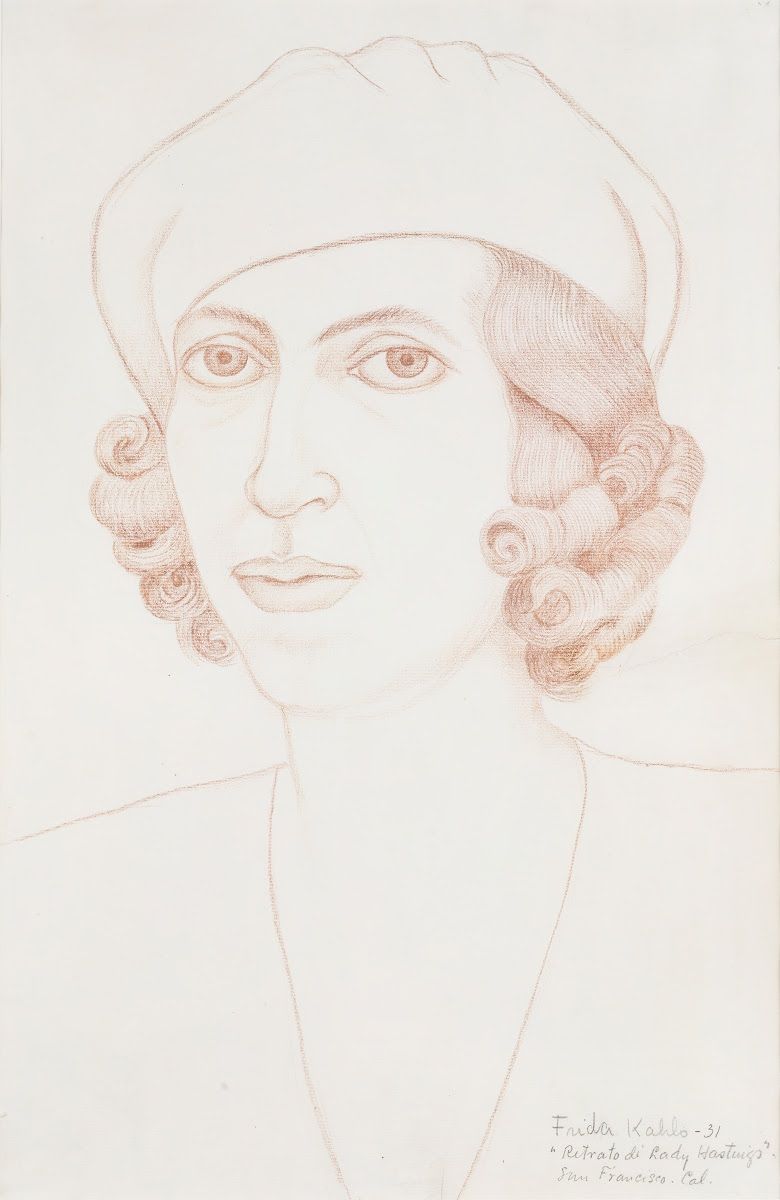

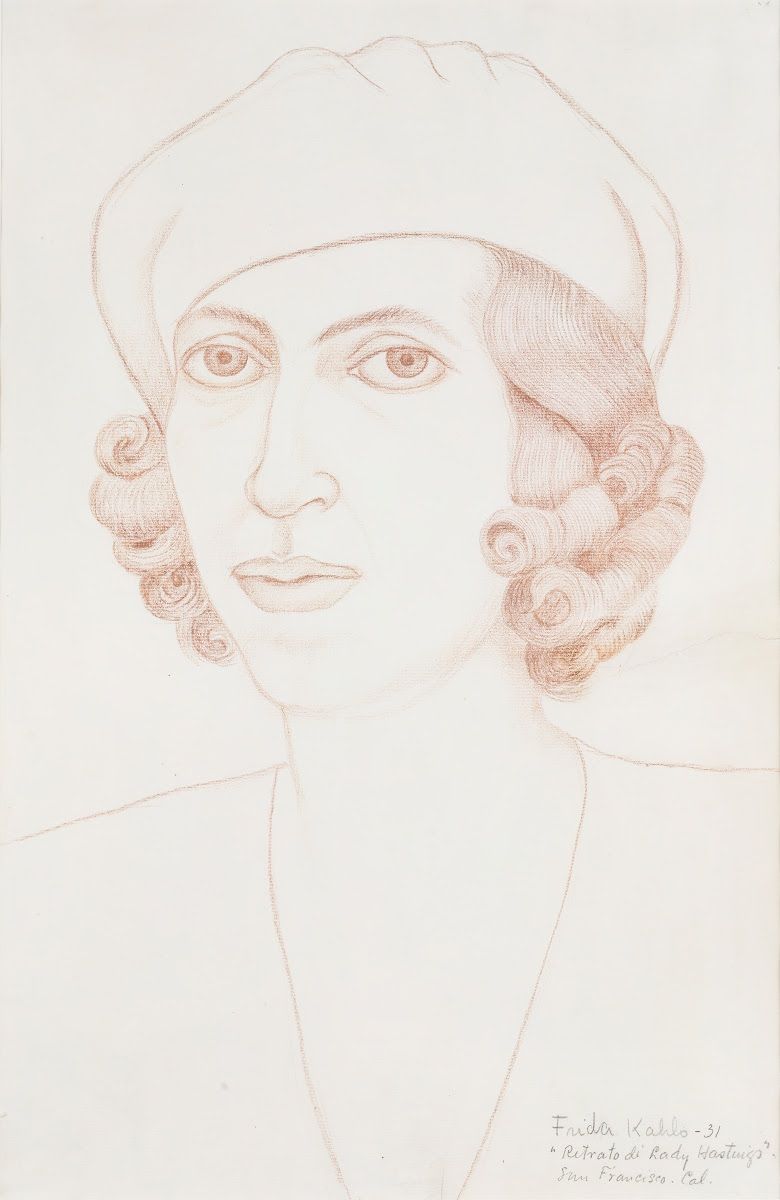

When Frida Kahlo discovered Diego Rivera's latest dalliance with the model

for his nude centrepiece, the Earth Mother "Califia", appearing in the

Luncheon Club's stairway mural, Helen Wills Moody, the American tennis star,

she began her own sexual dalliance with

Christina Hastings, the wife

of one of Diego's assistants, who also had time on her hands. The lesbian

affair resulted in a pencil portrait of her lover titled Lady Christina

Hastings.

Among the better known of Josephine

Baker's lesbian lovers were

Clara Smith, a black blues singer who secured Baker her first job as a chorus girl, and in Europe fellow

black American expatriate performer Bricktop (Ada Smith), French novelist

Colette, and (if Julie Taymor's

2002 movie Frida is to be believed) Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.

Bisexual Mexican artist Frida Kahlo has become an international icon for the power

and intensity of her art, and the extraordinary suffering that she experienced in life.

Born in Mexico on July 6, 1907 to a German photographer and his Mexican second

wife, Kahlo became a central figure in revolutionary Mexican politics and twentiethcentury

art. When childhood polio damaged one leg, the six year-old's reaction was to

become an athlete, an early indication of her courage and independence.

by Carl Van Vechten

Portrait of Lady Cristina Hasting - Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo, 1951, by Gisèle Freund

In 1925, at the age of eighteen, Kahlo suffered appalling injuries in a streetcar

accident, when she was impaled by an iron handrail smashing through her pelvis.

Multiple fractures to her spine, foot, and pelvic bones meant that the rest of her life

was dominated by a struggle against severe pain and disability; she underwent thirtytwo

operations in thirty years. She died at the age of 47 on July 13, 1954, possibly a

suicide.

Following her accident Kahlo started painting, becoming an important surrealist. Her

paintings, mostly self-portraits, employ the iconography of ancient Mesoamerican

cultures to depict both her physical suffering and her passion for Mexican politics and for the love of her

life, Diego Rivera, whom she married in 1929.

A famous painter of heroic revolutionary murals, Rivera was much older than Kahlo and incapable of sexual

fidelity. When he began an affair with her sister, Kahlo left Mexico. However, she forgave him this and other

infidelities. She divorced Diego in 1940, but remarried him later the same year.

Both artists had numerous affairs. Among Kahlo's lovers were Leon Trotsky and other men, but they also

included several women. Available evidence suggests that her male lovers were more important to Kahlo

than her lesbian affairs. Her friend Lucienne Bloch recalled Rivera saying, "You know that Frida is a

homosexual, don't you?" But the complexity of the artists' marriage warns against taking this statement at

face value.

However, Kahlo's queer significance is greater than her few lesbian liaisons suggest or even her

representations of women, some of which are homoerotic. She was a masterly and magical exponent of

cross-dressing, deliberately using male "drag" to project power and independence. A family photograph

from 1926 shows her in full male attire, confronting the camera with a gaze best described as cocksure. So

soon after her accident, this cockiness must have concealed unimaginable pain.

Clothes were extremely important to Kahlo. Although she was much more comfortable in slacks, she

adopted ornate Mexican costumes on visits abroad and when at home with Rivera. Her "exotic" beauty was

much admired; she was photographed by most of the leading art photographers of the time; and her visit to

Paris led to the creation of the "Robe Madame Rivera," an haute couture version of her famous peasant costume.

If Kahlo used dress to make a nationalist political point, she also used it to make a statement about her

own independence from feminine norms. Several photographic studies show her in men's clothing, and in

one famous self-portrait she sits, shaven-headed, wearing a man's suit, surrounded by discarded tresses.

Heterosexual Freudian Laura Mulvey interprets this as mourning the wounded, castrated female body. A

more positive feminist or queer reading recognizes the use of "butch drag" throughout her work to signify

strength and independence.

Kahlo was troubling gender long before "lesbian boys" were invented.

Julie Taymor's film, Frida (2002), starring Salma Hayek as the artist, enshrined Kahlo in

the popular imagination as a bisexual icon.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈfɾiða ˈkalo]; 6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954[1]) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by the country's popular culture, she employed a naïve folk art style to explore questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class, and race in Mexican society.[2] Her paintings often had strong autobiographical elements and mixed realism with fantasy. In addition to belonging to the post-revolutionary Mexicayotl movement, which sought to define a Mexican identity, Kahlo has been described as a surrealist or magical realist.[3] She is known for painting about her experience of chronic pain.[4]

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈfɾiða ˈkalo]; 6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954[1]) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by the country's popular culture, she employed a naïve folk art style to explore questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class, and race in Mexican society.[2] Her paintings often had strong autobiographical elements and mixed realism with fantasy. In addition to belonging to the post-revolutionary Mexicayotl movement, which sought to define a Mexican identity, Kahlo has been described as a surrealist or magical realist.[3] She is known for painting about her experience of chronic pain.[4]