Queer Places:

Flint Cottage, The Zigzag, Mickleham, Dorking RH5 6BN, UK

Dorking Cemetery

Dorking, Mole Valley District, Surrey, England

George

Meredith OM (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and

poet of the Victorian era. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in

Literature seven times.[1]

Some novels in the XIX century presented relationship between women in

positive and central terms, such as that between Diana Warwick and Emma

Dunstane in George Meredith's Diana of the Crossways (1885). Set in the

1830s and 1840s, the novel was loosely based on the experiences of

Caroline Norton, a society

hostess whose husband tried and failed to diveroce her for an alleged

affair with Whig Prime Minister Lord Melbourne and who was subsequently

accused of passing a Cabinet secret, learned for an admirer, to The Times.

However, the central relationship in the novel is one between two women,

Diana Warwick (Caroline Norton) and Emma Dunstane.

George

Meredith OM (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and

poet of the Victorian era. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in

Literature seven times.[1]

Some novels in the XIX century presented relationship between women in

positive and central terms, such as that between Diana Warwick and Emma

Dunstane in George Meredith's Diana of the Crossways (1885). Set in the

1830s and 1840s, the novel was loosely based on the experiences of

Caroline Norton, a society

hostess whose husband tried and failed to diveroce her for an alleged

affair with Whig Prime Minister Lord Melbourne and who was subsequently

accused of passing a Cabinet secret, learned for an admirer, to The Times.

However, the central relationship in the novel is one between two women,

Diana Warwick (Caroline Norton) and Emma Dunstane.

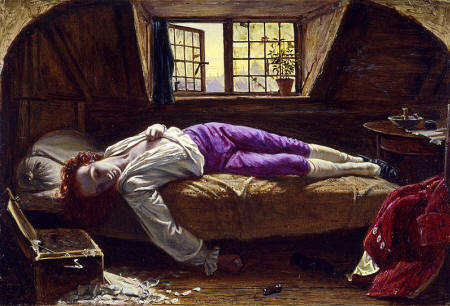

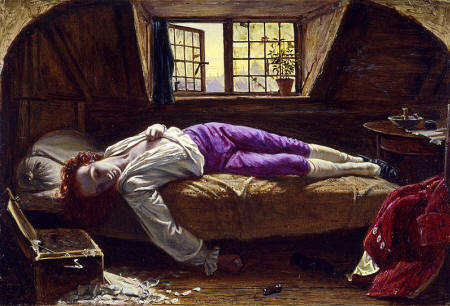

The Death of Chatterton by Henry Wallis, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery version, for which Meredith posed in 1856

Meredith was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire,

a son and grandson of naval outfitters.[2] His

mother died when he was five. At the age of 14 he was sent to a Moravian School

in Neuwied, Germany,

where he remained for two years. He read law and was articled as a

solicitor, but abandoned that profession for journalism and poetry. He

collaborated with Edward

Gryffydh Peacock, son of Thomas

Love Peacock, in publishing a privately circulated literary magazine,

the Monthly Observer.[3] He

married Edward Peacock's widowed sister Mary Ellen Nicolls in 1849 when he

was twenty-one years old and she was twenty-eight.[2]

Meredith collected his early writings, first published in periodicals, in

an 1851 volume, Poems. In 1856 he posed as the model for The

Death of Chatterton, a notable painting by the English Pre-Raphaelite painter Henry

Wallis (1830–1916).[4] His

wife ran off with Wallis in 1858; she died three years later. The

collection of sonnets entitled Modern Love (1862) emerged from this

experience as did The

Ordeal of Richard Feverel, his first major novel.[2]

Meredith married Marie Vulliamy in 1864 and settled in Surrey,

first in Norbiton and

then, at the end of 1867, near Box

Hill. He continued writing novels and poetry, often inspired by

nature. He had a keen understanding of comedy and his Essay on

Comedy (1877) remains a reference work in the history of comic theory. In The

Egoist, published in 1879, he applies some of his theories of comedy

in one of his most enduring novels. Some of his writings, including The

Egoist, also highlight the subjugation of women during the Victorian

period. During most of his career, he had difficulty achieving popular

success. His first successful novel was Diana of the Crossways published

in 1885.[5]

Meredith supplemented his often uncertain writer's income with a job as a

publisher's reader. His advice to Chapman and Hall made him influential in

the world of letters. His friends in the literary world included, at

different times, William and Dante

Gabriel Rossetti, Algernon

Charles Swinburne, Cotter

Morison,[6] Leslie

Stephen, Robert

Louis Stevenson, George

Gissing and J. M.

Barrie. Gissing wrote

in a letter to his brother Algernon that Meredith's novels were 'of the

superlatively tough species'.[7] His

contemporary Sir Arthur

Conan Doyle paid him homage in the short-story "The

Boscombe Valley Mystery", when Sherlock

Holmes says to Dr.

Watson during the discussion of the case, "And now let us talk about

George Meredith, if you please, and we shall leave all minor matters until

to-morrow." Oscar

Wilde, in his dialogue "The

Decay of Lying", implies that Meredith, along with Balzac,

is his favourite novelist, saying "Ah, Meredith! Who can define him? His

style is chaos illumined by flashes of lightning". In 1868 Meredith was

introduced to Thomas

Hardy by Frederic

Chapman of Chapman

& Hall the publishers. Hardy had submitted his first novel, The Poor

Man and the Lady. Meredith advised Hardy not to publish his book as it

would be attacked by reviewers and destroy his hopes of becoming a

novelist. Meredith felt the book was too bitter a satire on the rich and

counselled Hardy to put it aside and write another 'with a purely artistic

purpose' and more of a plot. Meredith spoke from experience; his first big

novel, The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, was judged so shocking that Mudie's

circulating library had cancelled an order of 300 copies. Hardy continued

in his attempts to publish the novel: however it remained unpublished,

though he clearly took Meredith's advice seriously.[8]

Meredith's politics were those of a Radical Liberal and

he was friends with other Radicals such as Frederick

Maxse and John

Morley.[9][10]

Meredith had two wives and three children. He outlived both wives and

one child. On 9 August 1849, Meredith married Mary Ellen Nicolls (née

Peacock), a beautiful widow with a daughter. They had one child, Arthur

(1853–1890). In 1858 she ran off with the painter Henry Wallis, shortly

before giving birth to a child assumed to be Wallis's. Mary Ellen died in

1861.[12][13]

On 20 September 1864, Meredith married Marie Vulliamy. She died of cancer

in 1886.[13]

Meredith had three children: with Mary Ellen, Arthur Gryffydh (1853–1890),

with Marie, William Maxse (1865–1937)[13]

and Marie Eveleen (known as Mariette) (1871–1933). She married Henry

Parkman Sturgis. Before

his death, Meredith was honoured from many quarters: he succeeded Lord

Tennyson as president of the Society

of Authors; in 1905 he was appointed to the Order

of Merit by King

Edward VII.[2]

In 1909, he died at his home in Box

Hill, Surrey.[2] He

is buried in the cemetery at Dorking,

Surrey, which his residence Flint Cottage overlooked.[11]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

George

Meredith OM (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and

poet of the Victorian era. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in

Literature seven times.[1]

Some novels in the XIX century presented relationship between women in

positive and central terms, such as that between Diana Warwick and Emma

Dunstane in George Meredith's Diana of the Crossways (1885). Set in the

1830s and 1840s, the novel was loosely based on the experiences of

Caroline Norton, a society

hostess whose husband tried and failed to diveroce her for an alleged

affair with Whig Prime Minister Lord Melbourne and who was subsequently

accused of passing a Cabinet secret, learned for an admirer, to The Times.

However, the central relationship in the novel is one between two women,

Diana Warwick (Caroline Norton) and Emma Dunstane.

George

Meredith OM (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and

poet of the Victorian era. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in

Literature seven times.[1]

Some novels in the XIX century presented relationship between women in

positive and central terms, such as that between Diana Warwick and Emma

Dunstane in George Meredith's Diana of the Crossways (1885). Set in the

1830s and 1840s, the novel was loosely based on the experiences of

Caroline Norton, a society

hostess whose husband tried and failed to diveroce her for an alleged

affair with Whig Prime Minister Lord Melbourne and who was subsequently

accused of passing a Cabinet secret, learned for an admirer, to The Times.

However, the central relationship in the novel is one between two women,

Diana Warwick (Caroline Norton) and Emma Dunstane.