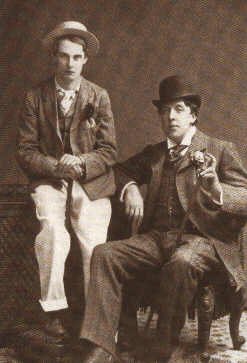

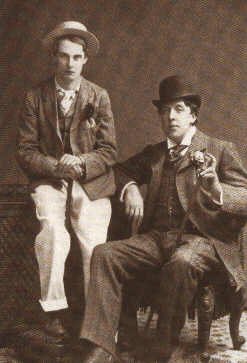

Partner Lord Alfred Douglas

Queer Places:

Oscar Wilde Centre, 21 Westland Row, Dublin 2, Ireland

American College Dublin, 2 Marino Park, Merrion Square West, Dublin, Ireland

Portora Royal School, Derrygonnelly Rd, Enniskillen BT74 7EY, UK

Trinity College Dublin, College Green, Dublin 2, Co. Dublin, Ireland

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

13 Salisbury St, Marylebone, London NW8 8DE, UK

44 Tite St, Chelsea, London SW3, UK

9 Carlos Pl, Mayfair, London W1K 3AT, UK

34 Tite St, Chelsea, London SW3 4JA, UK

10 St James's Pl, St. James's, London SW1A 1NP, UK

2 Courtfield Gardens, Earls Court, London SW5 0PA, UK

31 Bedford Way, Bloomsbury, London WC1B 5DR, UK

Fielden House, 13 Little College St, Westminster, London SW1P 3SH, UK

80 Strand, London WC2R 0ZA, UK

Belmond Cadogan Hotel, 75 Sloane St, London SW1X 9SG, UK

Hotel Café Royal, 68 Regent St, London W1B 4DY, UK

Brown's Hotel, Albemarle St, Mayfair, London W1S 4BP, UK

The Savoy, Strand, London WC2R 0EU, UK

Hôtel d’Alsace, 13 Rue des Beaux Arts, 75006 Paris, Francia

Albergo Victoria, Corso Umberto, 81, 98039 Taormina ME

Père Lachaise Cemetery, 16 Rue du Repos, 75020 Paris, Francia

Westminster Abbey, 20 Deans Yd, Westminster, London SW1P 3PA, UK

Oscar

Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an

Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the

1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s.

He is best remembered for his epigrams and plays, his novel The Picture of

Dorian Gray, and the circumstances of his imprisonment and early death.

Wasted Days (1877) and The Portrait of Mr. W.H. (1889-95) are cited as examples in Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English

Literature from 1850-1900, by Brian Reade. He appears as Esmé Amarinth in

the novel The Green Carnation (1894) by

Robert Hichens.

Reginald Bunthorne in Gilbert and Sullivan's opera Patience (1881) was

widely believed to have been based on Wilde, but it was originally meant to

be a caricature of

Algernon Charles Swinburne. The character of Toad of Toad Hall in The

Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Grahame was modelled on Wilde. Claude

Davenant in Mirage (1887) by George Fleming (pen-name of Julia Constance

Fletcher) is believed to be a portrait of Wilde. Cardinal Pirelli in The

Princess Zoubaroff (1920), the play by

Ronald Firbank, is thought to

be a composite of Wilde and the author himself. Wilde appears again in the

same play as Lord Orkish. Gabriel Nash in

Henry James' The Tragic Muse

(1890) is believed to be part portrait of Wilde.

Oscar

Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an

Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the

1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s.

He is best remembered for his epigrams and plays, his novel The Picture of

Dorian Gray, and the circumstances of his imprisonment and early death.

Wasted Days (1877) and The Portrait of Mr. W.H. (1889-95) are cited as examples in Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English

Literature from 1850-1900, by Brian Reade. He appears as Esmé Amarinth in

the novel The Green Carnation (1894) by

Robert Hichens.

Reginald Bunthorne in Gilbert and Sullivan's opera Patience (1881) was

widely believed to have been based on Wilde, but it was originally meant to

be a caricature of

Algernon Charles Swinburne. The character of Toad of Toad Hall in The

Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Grahame was modelled on Wilde. Claude

Davenant in Mirage (1887) by George Fleming (pen-name of Julia Constance

Fletcher) is believed to be a portrait of Wilde. Cardinal Pirelli in The

Princess Zoubaroff (1920), the play by

Ronald Firbank, is thought to

be a composite of Wilde and the author himself. Wilde appears again in the

same play as Lord Orkish. Gabriel Nash in

Henry James' The Tragic Muse

(1890) is believed to be part portrait of Wilde.

Wilde's parents were successful Anglo-Irish intellectuals in Dublin. Their

son became fluent in French and German early in life. At university, Wilde

read Greats; he proved himself to be an outstanding classicist, first at

Dublin, then at Oxford. He became known for his involvement in the rising

philosophy of aestheticism, led by two of his tutors,

Walter Pater and John

Ruskin. After university, Wilde moved to London into fashionable cultural and

social circles.

As a spokesman for aestheticism, he tried his hand at various literary

activities: he published a book of poems, lectured in the United States and

Canada on the new "English Renaissance in Art" and interior decoration, and

then returned to London where he worked prolifically as a journalist. Known

for his biting wit, flamboyant dress and glittering conversational skill,

Wilde became one of the best-known personalities of his day. At the turn of

the 1890s, he refined his ideas about the supremacy of art in a series of

dialogues and essays, and incorporated themes of decadence, duplicity, and

beauty into what would be his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray

(1890). The opportunity to construct aesthetic details precisely, and combine

them with larger social themes, drew Wilde to write drama. He wrote Salome

(1891) in French while in Paris but it was refused a licence for England due

to an absolute prohibition on the portrayal of Biblical subjects on the

English stage. Unperturbed, Wilde produced four society comedies in the early

1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights of late-Victorian

London.

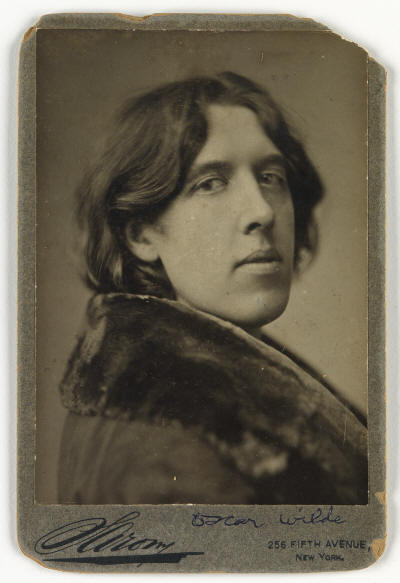

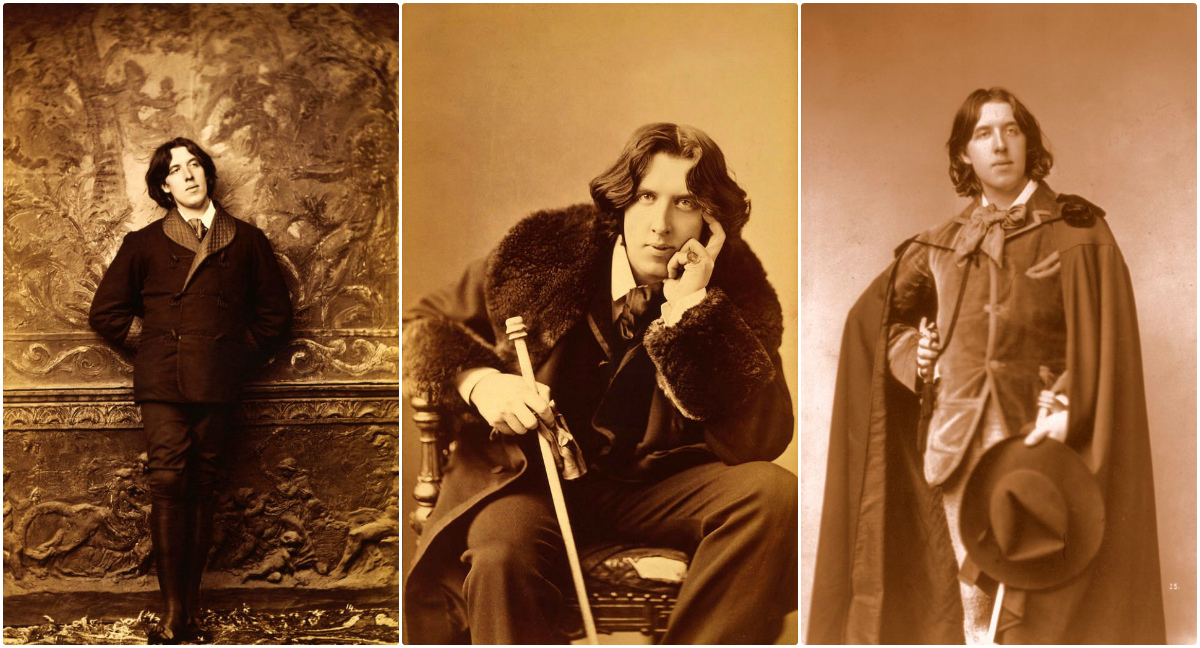

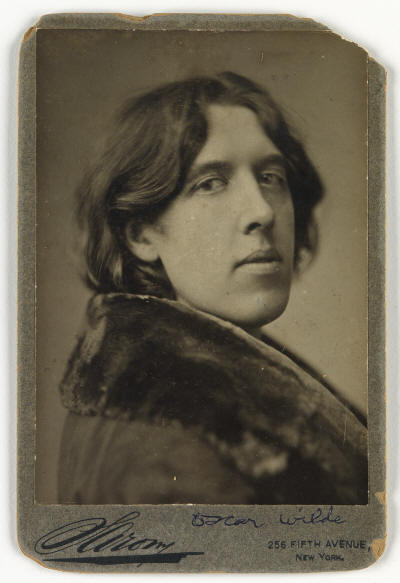

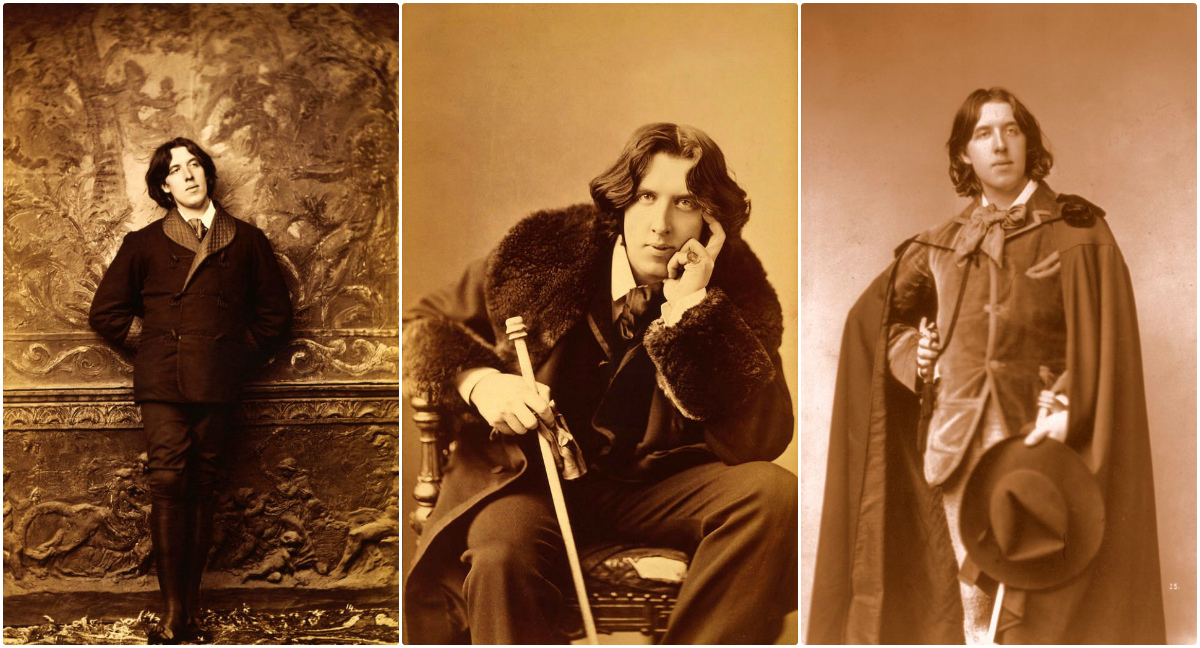

NAPOLEON SARONY (1821-1896)

Oscar Wilde.

Albumen print, the image measuring 139.7x98.4 mm; 5 1/2x3 7/8 inches, the Sarony mount 165.1x111.1 mm; 6 1/2x4 3/8 inches, with Sarony's printed credit and address, and the sitter's credit, in ink, in an unknown hand, on mount recto, and the Culver Pictures label, bar code, and hand stamp, on mount verso. 1882.

This photograph was part of the 1882 portrait sitting Oscar Wilde did at Sarony's studio when he began his American lecture tour. During the portrait sitting, Wilde posed for at least 27 pictures in various attire which he anticipated would be distributed to cities in advance of his arrival. It is likely that this was his preferred image, which he described as "the photograph of me with my head looking over my shoulder."

by Robert Goodloe Harper Pennington, c. 1884

.jpg)

Oscar Wilde by Napoleon Sarony

.JPG)

10 St James's Pl, St. James's, London

.JPG)

The Savoy, London

Quisisana, Capri

Westminster Abbey, London

Today, Frank Miles is best known as a friend of Oscar

Wilde whom he met at Oxford in 1874 or 1875, where Miles had family

connections to the colleges and friends. Miles introduced Wilde to

Lillie Langtry, and to his friend and patron Lord

Ronald Gower, who later became the model for

the worldly Lord Henry Wotton in Wilde's novel

The Picture of Dorian Gray and Gower's circle was the inspiration for

The Portrait of Mr. W.H. (1889). Miles and Wilde took up a

residence together in Tite Street.

If some historians are to be believed, until 1877 Wilde had had no same-sex

intimacies, and would not until he had a relationship with

Robert Ross in 1886.

Oscar Wilde appeared in America in 1882 on a lecture tour in part designed

to promote the Gilbert and Sullivan opera Patience; or, Bunthorne’s Bride. The

opera’s main character represented an aesthete—perhaps modeled on Wilde or the

poet Algernon Charles Swinburne—who posed with a giant sunflower while

spouting his opinions on the latest cultural trends.

When asked by a reporter upon docking in New York who were the greatest

American literary figures, Oscar Wilde at once answered

Walt Whitman, but in the same

breath insisted also on

Ralph Waldo Emerson—“New

England’s Plato,” Wilde called him, whose “Attic genius” he thought so highly

of that when he was in prison and allowed to choose only a few books, one was

Emerson’s essays. He quoted from Emerson twice in De Profundis—and very

significant quotes they were: “Nothing is more rare in any man than an act of

his own”; “all martyrdoms seemed mean to the lookers on.” According to Richard

Ellmann, Wilde (who after his visit to Whitman answered not one but all

questions about the American poet’s sexuality for years to come by repeating,

“The kiss of Walt Whitman is still on my lips”) expanded on the matter

significantly: under an inscription by Whitman, Wilde (quoting himself about

Wordsworth; it was nothing if not a literary age) wrote of Whitman: “The

spirit who living blamelessly but dared to kiss the smitten mouth of his own

century.”

To Charles Eliot Norton,

Harvard’s (and America’s) first professor of fine arts, Paul Ruskin’s friend,

and himself the leading art arbiter in America of his time, Oscar Wilde wrote:

“I am in Boston for a few days and hope you will allow me the pleasure of

calling on you.” Doubtless Wilde enclosed his letter of recommendation to

Norton from the Pre-Raphaelite master

Edward Burne-Jones (“any kindness shown

to him is shown to me”).

When in 1882 Wilde announced to Henry

James, “I am going to Bossston; there I have a letter to the dearest

friend of my dearest friend—Charles Eliot Norton from Burne-Jones,” James was

not only offended at the name-dropping but, in Richard Ellmann’s words,

“revolted by Wilde’s knee breeches, contemptuous at the self-advertising … and

nervous about the sensuality … . James’s homosexuality was latent, Wilde’s

patent.”

Breakfast on Brattle Street with another Harvard professor, poet Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow—through a heavy snow—was rather more sober, but not,

Oscar Wilde insisted, less artistic: “When I remember Boston I think only of

that lovely old man, who is himself a poem,” Wilde said later.

At work at the Harvard Theatre Collection, Joan Navarre, an independent

scholar, stumbled across one of those stiff old sepia photographs of Oscar

Wilde, and, turning it over, encountered the great man’s autograph. Above it,

furthermore, Wilde had inscribed “To J. Wendell,” with the date 31 January

1882. It was the date of Wilde’s first Boston lecture, when he was notoriously

heckled by Evert J. Wendell’s

classmates, and the photograph all but proved Wendell to have been there,

heckler or no.

Clyde Fitch was the most successful

and prolific dramatist of his time, producing nearly sixty plays in a

twenty-year career. He was, at least for a short time in the late 1880s and early 90s, Oscar Wilde’s

lover, and Wilde influenced his early plays, but Fitch’s study of Ibsen and

other European dramatists inspired him to pursue the course of naturalism.

At the height of Wilde's fame and success, while The Importance of Being

Earnest (1895) was still being performed in London, Wilde had the Marquess

of Queensberry prosecuted for criminal libel. The Marquess was the father of

Wilde's lover,

Lord Alfred Douglas. The libel trial unearthed evidence that caused Wilde

to drop his charges and led to his own arrest and trial for gross indecency

with men.

Even after the shocking revelations of a homosexual underworld, there was

widespread support for Wilde. An Anglican clergyman paid half of his bail; the

other half was paid by the Marquis of Queensberry’s eldest surviving son. A

Jewish businessman offered him the free use of his yacht as a means of escape.

The servants of his friends the Leversons expressed sympathy with ‘poor Mr

Wilde’. The painter Louise Jopling

exchanged a ‘sorrowful’ glance with the newsboy who told her of the verdict.

W. B. Yeats, whose father urged him to testify for Wilde, brought letters of

support from several Irish writers. ‘Cultivated London’, said Yeats, ‘was now

full of his advocates.’ When Wilde gave his moving speech on ‘the Love that

dare not speak its name’, the hissing from the public gallery was drowned out

by applause.

After the trial, there were letters to the press protesting at Wilde’s

treatment. The popular journalist W. T. Stead pointed out that Wilde’s

‘unnatural’ propensities were not unnatural for him, and that if he had

committed adultery with his friend’s wife or corrupted young girls instead of

boys, ‘no one could have laid a finger upon him’. Even The Illustrated Police

Budget was sorry that ‘one of the most brilliant wits, epicures, and

epigrammatists we have seen in England for years’ had ‘passed from the light

of freedom’.

After two more trials Oscar Wilde was convicted and sentenced to two years'

hard labour, the maximum penalty, and was jailed from 1895 to 1897. In Paris,

the French-American poet Stuart

Merrill drew up a petition asking for the sentence to be reduced. Almost

everyone refused to sign, including Émile Zola. A British petition, prepared

by More Adey, was even less successful.

Magnus Hirschfeld had wider aims and a

more diverse audience and was consequently more effective. He and his

journalist friend Leo Berg sent letters of

protest to the newspapers and Hirschfeld set to work on the first of his many

books: Sappho und Sokrates, or ‘How can one explain the love of men and women

for people of the same sex?’ It was published pseudonymously by a

young Leipzig publisher called Max Spohr. Spohr

had already published two pro-homosexual works and was to prove remarkably

resistant to prosecution.

During his

last year in prison, he wrote De Profundis (published posthumously in

1905), a long letter which discusses his spiritual journey through his trials,

forming a dark counterpoint to his earlier philosophy of pleasure. On his

release, he left immediately for France, never to return to Ireland or

Britain. There he wrote his last work, The Ballad of Reading Gaol

(1898), a long poem commemorating the harsh rhythms of prison life.

After his release from prison, Oscar Wilde was persuaded by

Ernest Dowson to visit a

prostitute in Dieppe in order to acquire ‘a more wholesome taste’. When he

emerged from the brothel, a small crowd, supposedly, had gathered in the

street. He whispered to Dowson, ‘The first these ten years, and it shall be

the last. It was like chewing cold mutton!’ Then, in a louder voice: ‘But tell

it in England, for it will entirely restore my character!’

In 1898 Sergei Diaghilev

toured Berlin, London and Paris, borrowing works of art to exhibit in St

Petersburg. In Paris he sought out the exiled

Oscar Wilde. Diaghilev was already a

striking sight, tall and elegant, with an early white streak in his

hair; the pair of them must have gone rather well together. Seeing them

walking arm in arm, the women prostitutes are said to have stood on café

chairs to hurl abuse at two such obvious threats to their business.

He died

destitute in Paris at the age of 46.

David

Diamond's Psalm, an orchestral piece of that year, was inspired by a visit

to Oscar Wilde’s grave in Père Lachaise and

dedicated to André Gide.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oscar_Wilde

- Robb, Graham. Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century .

Pan Macmillan. Edizione del Kindle.

- Bachelors of a Different Sort, Queer Aesthetics, Material Culture

and the Modern Interior in Britain, by John Potvin

- Rossini, Gill. Same Sex Love 1700-1957: A History and Research Guide .

Pen and Sword. Edizione del Kindle.

- Woods, Gregory. Homintern . Yale University Press. Edizione del

Kindle.

- Homosexuals in History, A Study of Ambivalence in Society, Literature

and the Arts, by A.L. Rowse, 1977

- Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English Literature from

1850-1900, by Brian Reade

- Wagner, R. Richard. We’ve Been Here All Along . Wisconsin Historical

Society Press. Edizione del Kindle.

- Shand-Tucci, Douglass. The Crimson Letter . St. Martin's Publishing

Group. Edizione del Kindle.

Oscar

Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an

Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the

1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s.

He is best remembered for his epigrams and plays, his novel The Picture of

Dorian Gray, and the circumstances of his imprisonment and early death.

Wasted Days (1877) and The Portrait of Mr. W.H. (1889-95) are cited as examples in Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English

Literature from 1850-1900, by Brian Reade. He appears as Esmé Amarinth in

the novel The Green Carnation (1894) by

Robert Hichens.

Reginald Bunthorne in Gilbert and Sullivan's opera Patience (1881) was

widely believed to have been based on Wilde, but it was originally meant to

be a caricature of

Algernon Charles Swinburne. The character of Toad of Toad Hall in The

Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Grahame was modelled on Wilde. Claude

Davenant in Mirage (1887) by George Fleming (pen-name of Julia Constance

Fletcher) is believed to be a portrait of Wilde. Cardinal Pirelli in The

Princess Zoubaroff (1920), the play by

Ronald Firbank, is thought to

be a composite of Wilde and the author himself. Wilde appears again in the

same play as Lord Orkish. Gabriel Nash in

Henry James' The Tragic Muse

(1890) is believed to be part portrait of Wilde.

Oscar

Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an

Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the

1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s.

He is best remembered for his epigrams and plays, his novel The Picture of

Dorian Gray, and the circumstances of his imprisonment and early death.

Wasted Days (1877) and The Portrait of Mr. W.H. (1889-95) are cited as examples in Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English

Literature from 1850-1900, by Brian Reade. He appears as Esmé Amarinth in

the novel The Green Carnation (1894) by

Robert Hichens.

Reginald Bunthorne in Gilbert and Sullivan's opera Patience (1881) was

widely believed to have been based on Wilde, but it was originally meant to

be a caricature of

Algernon Charles Swinburne. The character of Toad of Toad Hall in The

Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Grahame was modelled on Wilde. Claude

Davenant in Mirage (1887) by George Fleming (pen-name of Julia Constance

Fletcher) is believed to be a portrait of Wilde. Cardinal Pirelli in The

Princess Zoubaroff (1920), the play by

Ronald Firbank, is thought to

be a composite of Wilde and the author himself. Wilde appears again in the

same play as Lord Orkish. Gabriel Nash in

Henry James' The Tragic Muse

(1890) is believed to be part portrait of Wilde.

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)