Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Columbia University (Ivy League), 116th St and Broadway, New York, NY 10027

Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site, 105 Brattle St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ("Harry") Dana (January 26, 1881 - April 26, 1950), Harvard AB 1903, AM 1904, PhD

1910 taught English at the University of Paris (Sorbonne) from 1908 to

1910 and comparative literature at Columbia University from 1912 to

1917, when he was dismissed for pacifist activities. Thereafter he

continued to teach compartive literature and Russian studies at a

variety of educational institutions and was deeply involved in

progressive political activities, particularly in advancing the cause of

global socialism and supporting labor unions and worker education.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ("Harry") Dana (January 26, 1881 - April 26, 1950), Harvard AB 1903, AM 1904, PhD

1910 taught English at the University of Paris (Sorbonne) from 1908 to

1910 and comparative literature at Columbia University from 1912 to

1917, when he was dismissed for pacifist activities. Thereafter he

continued to teach compartive literature and Russian studies at a

variety of educational institutions and was deeply involved in

progressive political activities, particularly in advancing the cause of

global socialism and supporting labor unions and worker education.

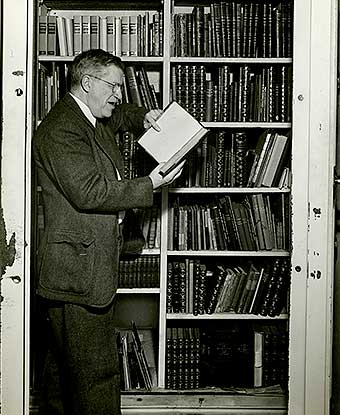

Born in 1881 to Longfellow’s daughter, Edith (subject of “The Children’s Hour”), and Richard Henry Dana III (the son of the author of Two Years Before the Mast), Harry Dana was raised on Brattle Street in another and later family mansion adjoining Castle Craigie itself. After Browne and Nichols School in Cambridge, he entered Harvard College, where his grandfather, the poet, had been a professor; young Harry graduated with the class of 1903. He then taught for several years at St. Paul’s School, in Concord, New Hampshire, perhaps the most prestigious of the exclusive Anglican New England boarding schools, then at another school in California—the first sign of his adventurousness—before returning to Harvard in 1906 as a graduate student in the English department. Teaching assistant to that legendary grandee of the English department Barrett Wendell, Dana taught at Harvard for several years, taking his Ph.D. in 1910. Thereafter he studied in Paris. He taught briefly at the Sorbonne and actually founded the Harvard Club of Paris. In 1912 he took up what he had every reason to think was a career teaching appointment at Columbia. A traveler, in 1914 he found himself in Europe at the start of World War I: “I was in the crowd under the Kaiser’s balcony when he declared war,” he reported in his Harvard class notes; and then “in Paris I stood with the people in the streets watching the German aeroplanes flying over the city just before the Battle of the Marne.”

Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site, 105 Brattle St, Cambridge, MA 02138

By the time Dana was a graduate student in Paris he was part of the gay underground of the period, a genial and popular figure evidently, and for the first time can be linked as a student to Morton Fullerton A letter of Fullerton’s to Dana in Paris in 1911 refers to one Chafee as “a peculiarly winsome youth” and counts on Dana to join them both at “a rendezvous to which I am looking forward with delight.” If his acquaintance with Fullerton proves that, as a young man, Dana was no stranger to the fast lane, to understand Dana’s character fully, one must take account of an early love that was to become a lifelong relationship, albeit at a distance, with a man his own age, Karl Young, who became a professor at Yale.

Letters from as early as 1908 survive, documenting the men’s intimacy. On September 1 Young wrote to Dana: “The days with you in Europe were lovely … . I was not disappointed. They were far dearer even than I had hoped.” On September 13: “I don’t suppose I could make you realize how happy I was with you and how deeply I was comforted by the strengthening of the bonds between us. I feel that we’ve never meant so much to each other before.” The complimentary close of 1908—“affectionately your friend”—had by 1910 become “Lovingly your Karl”; and by 1911, “Ever your loving Karl.” A long letter, undated, aptly discloses the troubled but long-lived nature of Dana and Young’s relationship, so characteristic of the time: Can’t you decide, dear Harry, that I am, perchance, as sincere and straightforward as most people, and can’t it occur to you that your companionship can help me very much. Honestly, Harry, it’s time for us to get down to business, for I can’t believe that you’ll deny me all that I want from you. Please don’t call it “patronizing” when I take a little interest in your work and do try to see something beside egotism in my telling you about my work …

Beginning in 1917, Dana was granted life tenancy of the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House at 105 Brattle St., Cambridge, Mass. and became its first curator when the residence was made a national monument and research center administered by the US National Park Service.

Having been in Europe at the outbreak of WWI, Dana was a passionate pacifist who was fired from Columbia University for his anti-war activities: “In June, 1917, at the end of my fifth year as instructor in English at Columbia University, I was promoted to the position of assistant professor of comparative literature. In October, however, at the beginning of the next academic year,” Dana was dismissed “on account of my activities for ‘international peace [with the People’s Council of America for Democracy and Peace, an organization opposed to American entrance into the war].”

He hardly taught again in any sustained way—except at New York’s prestigious New School for Social Research in the 1920s. But Dana, who by then had taken up residence in Longfellow House with his Aunt Alice, continued his work as a scholar in his field, work that dovetailed with his increasingly socialist—indeed, communist—politics.

In the years between the two World Wars Dana lectured at the Progressive Labor School of Boston and the Rand School in New York, was the founder of the Boston Central Labor Union’s Trade Union College and also of Young Democracy of America, as well as second vice president of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, editor of the Socialist Review, and an active member of the Harvard Teachers’ Union—all while still applying himself to his special field, Soviet drama, of which he became a leading authority. He spent year-long periods in the Soviet Union between 1927 and 1935, not only in Moscow and Leningrad but in Armenia and the Ukraine. He was in touch with such major cultural figures of the era as film director Sergei Eisenstein, and with Gorky and Stanislavsky, as well as in this country with Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis. By his own estimate Dana had seen over six hundred Soviet plays. He remained an adviser to the Harvard Dramatic Club and also wrote both books and magazine articles. Among his books, still useful today, are Handbook on Soviet Drama (1938), Drama in Wartime Russia (1943), and History of the Modern Drama (1947).

Throughout his life he traveled widely, living in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1928 and visiting major centers of European drama such as London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, and Budapest. The bulk of his literary oeuvre focused on Soviet drama; he also wrote a history of the Dana family, The Dana Saga, and produced an edition of the novel of his paternal grandfather, Richard Henry Dana, Jr., Two Years Before the Mast.

John Cheever attended bohemian parties on the Hill that were held in small apartments filled with athletic young men and a few older foreign women. There, he befriended older gay men including the poet Jack Wheelwright, and Henry Dana. The latter tried to bed Cheever, chasing him down the hall of the Longfellow House shouting, "how can you be so cruel?" when Cheever turned him down.

Dana was open about his homosexuality, which got him in trouble with the law in 1935. One night, four teenagers were arrested in Concord when they were joyriding in a car that belonged to Dana's nephew. This led one youth, a messenger boy of 16, to tell police about his relationship with Dana. Evidence was presented before a grand jury and Dana was arrested and arraigned. He was acuitted several months later but the charge was extensively reported in the press and led to the trustees of the Longfellow House to attempt eviction. They failed.

He virtually turned himself into the live-in curator of the Longfellow House, wrote widely on the subject (Longfellow and Dickens, for instance, published in 1943), and established the Longfellow Archives, today administered by the National Park Service, which took over the house when it was given to the nation in 1970.

No doubt it also scandalized many when the black actor, Paul Robeson, appearing nearby at the Brattle Theatre, was feted by Dana at the Longfellow House.

Robert Creeley remembers that for him and three or four of his mostly heterosexual friends, Dana’s apartment in the Longfellow House was a cherished refuge for freshmen at Harvard, where at ten or eleven at night the group could ring the doorbell in search of drink and talk and always be sure of good company. Creeley, today a leading American poet, recalls Dana as witty and droll, usually in his smoking jacket, drink in hand, often memorably wise in the way he eased youth’s often anxious moments in their first-year talk at college.

Not only strangers, but any adult male identified as queer by the grapevine or public exposure was a potential sex partner and/or shoulder to lean on for a younger gay man … . When Bertram Schaffner, a Harvard freshman (today a prominent New York psychiatrist in his eighties), turned up [at Dana’s doorstep], he wasn’t taking much of a risk … . At Harvard as elsewhere young Schaffner and other gay freshmen needed Dana and figures like him, one of whose functions in life was “introduc[ing to] their juniors,” in Loughery’s words, “the argot, history, and contours of a society previously hidden.”

My published books: