Queer Places:

163 Beach 135th St, Queens, NY 11694

University of Michigan, 1230 Murfin Ave, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Barnard College (Seven Sisters), 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027

Columbia University (Ivy League), 116th St and Broadway, New York, NY 10027

Vassar College (Seven Sisters), 124 Raymond Ave, Poughkeepsie, NY 12604

University of Wisconsin, 716 Langdon St, Madison, WI 53706

Howard

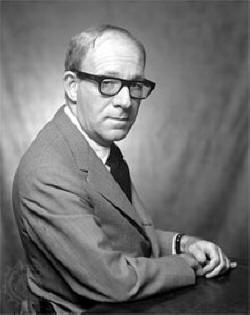

Ira Moss (January 22, 1922 – September 16, 1987), one of the leading figures of American letters in the latter half of the twentieth century, is

the author of a significant body of elegant, erudite, and urbane work, including literary criticism, essays,

plays, and most notably, poetry. Although Moss largely elided the subject of homosexuality in his poems, his work shares concerns with other

middle and late twentieth-century gay writing, such as the nature of identity, the imperfections of love,

and the decline of the body. As the influential gay poet and literary critic

J.D. McClatchy observed about

Moss, "everywhere his poems speak eloquently of the wounds of experience, the weather of the spirit."

Moss also served as poetry editor of the New Yorker for nearly 40 years. In his role at the magazine he was

instrumental in the support and promotion of the careers of many prominent American poets.

Howard

Ira Moss (January 22, 1922 – September 16, 1987), one of the leading figures of American letters in the latter half of the twentieth century, is

the author of a significant body of elegant, erudite, and urbane work, including literary criticism, essays,

plays, and most notably, poetry. Although Moss largely elided the subject of homosexuality in his poems, his work shares concerns with other

middle and late twentieth-century gay writing, such as the nature of identity, the imperfections of love,

and the decline of the body. As the influential gay poet and literary critic

J.D. McClatchy observed about

Moss, "everywhere his poems speak eloquently of the wounds of experience, the weather of the spirit."

Moss also served as poetry editor of the New Yorker for nearly 40 years. In his role at the magazine he was

instrumental in the support and promotion of the careers of many prominent American poets.

Howard Moss was born on January 22, 1922 in New York City. From 1939 to 1941, he attended the University of Michigan, where he received the distinguished Hopwood Award for Undergraduate Poetry. In 1942, he entered Harvard University; in 1943, he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Wisconsin. After a brief stint as a reviewer for Time in 1944, and an instructor at Vassar College from 1945 to 1946, Moss joined the editorial staff of the New Yorker in 1948, first as a fiction editor, and then two years later as poetry editor, a position he held at the magazine until shortly before his death in 1987. Among the poets Moss encouraged and promoted are Amy Clampitt, James Dickey, Galway Kinnell, Theodore Roethke, James Scully, and Richard Wilbur, and, especially, Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, and Mark Strand.

His own career as a poet spanned more than four decades. Beginning with the publication of The Wound and the Weather in 1946, when he was just twenty-four years old, Moss published fourteen books of poetry. Perhaps Moss's most critically acclaimed volume is Selected Poems (1971), which culled his best works from the 1960s and included seven new poems. His status as one of the nation's leading poets was confirmed when Selected Poems earned Moss both the 1972 National Book Award for poetry and election to the National Institute of Arts and Letters, one of the highest formal recognitions of artistic merit in the United States. Moss's New Selected Poems (1985), a collection of his best work, won the 1986 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize as the outstanding book of poetry published the previous year in the United States. Subsequently, Moss received a fellowship from the Academy of American Poets for "distinguished poetic achievement." J.D. McClatchy, writing in the Nation, recognized that New Selected Poems was "not just a collection of superb work," but was also a "long look at a career that has unfolded in surprising ways, and without the kind of critical recognition that has sustained others." He further noted that Moss's poetry "never fakes a pleasure or an insight," nor does it "pretend to emotions it does not feel." It is perhaps as an elegist--in his poems that mourn the loss of friends and family--that Moss will be best remembered. As McClatchy discerned, "the more compelling side of [Moss's] work is the elegiac." Beginning with "Elegy for My Father," first published in 1954, and "Small Elegy" (1956), on to "Water Island" (1960) and "September Elegy" (1964), and on through "Impatiens" (1978) and "Elegy for My Sister" (1978), Moss has written some of the most memorable and evocative contemporary examples of the genre.

Although comparatively open among friends about his sexuality, Moss rarely explored gay content explicitly in his poetry. Rather, he frequently employed the reticent, genderless, second-person singular in his more intimate, subjective verses, as in "And what were you trying to do / When you said, "You said we're through? " from the poem "Circle" (1963), and "Was that you flying down a flight of stairs / Into a thousand snowflakes of goodbye?" in "Three Winter Poems" (1971). Not that Moss's works are necessarily ambiguous or equivocal. He could be tart and transparent when contemplating certain aspects of gay culture, scrutinizing, for example, "last night's hunks of sex" weaving down the street, "still drunk," on their way home, in the poem "Nerves" (1983). Moss could also be trenchant when writing about the difficulties of attaining, and maintaining, love, attachments, and affection. In "The Rules of Sleep" (1982), which some critics have identified as a gay love poem, albeit one that is suffused with melancholy, "legs entwine to keep the body warm / Against the winter night," when a "sudden shift in position" lets "one body know the other's free to move / An inch away, and then a thousand miles." The poem ends with the searing, unsparing observation that "even intimacy / Is only another form of separation."

While primarily recognized as a poet, Moss also enjoyed a reputation as a literary critic and essayist, and although homosexuality is largely absent as an explicit subject in his poetry, it is a major concern in many of his essays. His first book of criticism, The Magic Lantern of Marcel Proust (1962), is an astute and perceptive study of the gay French novelist. Moss also published three collections of his critical writings, many of which first appeared in the New Yorker, including Writing Against Time: Critical Essays and Reviews (1969), Whatever is Moving (1981), and Minor Monuments: Selected Essays (1986). In his 1981 collection of essays, Whatever is Moving, Moss confronts homosexuality in the works of Walt Whitman, C.P. Cavafy, and James Schuyler. Moss contends that homosexuality informed Whitman's "most intense emotional affairs" and provided Cavafy with "built-in advantages as a spokesman for the city" of Alexandria, since as a gay man, he got to know it " in ways most people don't--strange places at strange hours." As for Schuyler, Moss admired his sexual frankness, remarking "He is in touch with parts of himself not usually available for examination and not often handled by most writers." Moss points out for particular attention Schuyler's sixty-page "The Morning of the Poem" (1980) and its rendering of the "men Schuyler has been attracted to, described lovingly." Additionally, Moss wrote essays on such significant glbtq writers as W.H. Auden, Elizabeth Bishop, Elizabeth Bowen, and Katherine Mansfield. Moss is also the author of four plays: The Folding Green (1954), Garden Music (1966), The Oedipus Mah- Jong Scandal (1968), and The Palace at 4 A.M. (1972), a poetic reinterpretation of the Oedipus myth. In addition to Vassar College, Moss taught at several other academic institutions, including Washington University (1972), Barnard College (1976), Columbia University (1977), University of California, Irvine (1979), and the University of Houston (1980).

Moss died of cardiac arrest on September 16, 1987. While he received accolades from critics and peers, as well as several prestigious awards, Moss's skills and artistry as a poet went largely underappreciated by the general public during his lifetime; he never achieved the fame or wide readership that many cultural commentators felt he deserved. "Partly as a consequence of [his role at the New Yorker] his own talent has been underrated," suggests the critic David Ray. "Yet he has with consistent productivity . . . turned out volume after volume and has dutifully and with impressive scholarship written criticism. He is, in short, an American man-of-letters in a sense largely missing from our literary culture." Bruce Bawer, the gay essayist and poet, echoed such sentiments in his tribute to Moss published in the New Criterion, noting that "the grace, refinement, and deep humanity of [Moss's] poetry will continue to draw readers to him when many of the more celebrated poets of our day are forgotten."

My published books: